We have many stories, some more famous than others, in which saints encounter and slay dragons, with St. George being the most well-known of them all. Most of these stories should be understood to be legendary, that is, not to be entirely historical; while there might be some historical basis behind them, that historical core is used to construct a legend which engages mythic, not historical dimensions. Then, through the mythic presentation of the event, symbols are used to present various theological truths. We do not have to believe that there was a literal dragon which was slain by George. Instead, dragons tend to represent Satan and other demonic entities which the saints overcome.

Nonetheless, there are other stories of saints which have dragons in them, stories which are much more historically based, and the dragon does not represent a symbol, but some animal which the saint encountered and engaged, an animal which we know by another name, such as a crocodile. In such stories, the saints, far from being hostile to the dragon in question, often found a way to be in harmony with them instead of seeking to destroy or harm them. That is, in these stories, we are shown the way humanity is meant to be in harmony with the rest of nature, including and especially, those creatures which are often seen as potentially being a threat. An example of this can be found in a story concerning Abba Agathon:

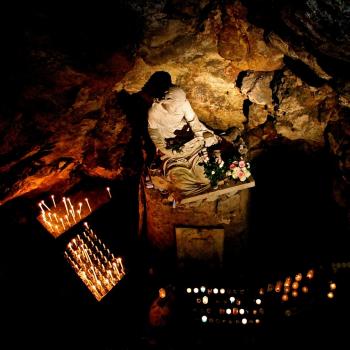

It is said of Abba Agathon that at one time he lived in a cave in the desert in which there was a large dragon. The serpent decided to go away and live him. Abba Agathon said to it, ‘If you leave, I am not saying here,’ so the serpent decided not to leave. Now there was a sycamore-fig in that desert. It was their custom to go out together. Abba Agathon marked a line in the sycamore and divided the tree with the serpent: the serpent would eat the fruit from one side of the sycamore while the elder ate from the other. When they had finished eating, they wet back into the cave, both of them together.[1]

Abba Agathon was a highly respected ascetic, who, even when he was young, was recognized for his holiness and was designated as an Abba by Abba Poemen, his mentor. It was due to his holiness that he looked to create peace within himself, but also with the world at large, a peace which allowed him to form relationships not only with other humans, but with animals. When he took residence in the cave, it is understandable that whatever type of animal was living in it, designated as a dragon, might have wanted to leave and find a new place to live. Animals, after all, often flee from human habitation.

Agathon did not want to impose himself on the dragon’s habitat and cause the creature to needlessly suffer, and so found a way to show it that they could live in harmony, sharing the fruit of the land with each other. As long as he lived in the cave, they were companions, with Agathon making sure he did not become a burden to the dragon. Once again, as with many such stories, we are shown the kind of harmony God wants humanity to have with animals. They are not supposed to be in rivalry with each other, but rather, they are meant to share the world together without adversely affecting each other. Humanity was meant to take in the lead of this, to act as stewards over creation, but due to the fall, humanity has failed to follow its calling, leading to various kinds of hostility between humans and the animals around them. Many stories of the saints are meant to show us the way humanity was meant to be, as they become more and more pure, and through that purity, restore their proper relationship with the world at large. Then, like Agathon, they not only find themselves in harmony with whatever animals they meet, they make sure they are of service to those animals as well.

Christians should look to the examples of those saints who show the kind of harmony that could exist between humanity and animals, saints like St. Francis of Assisi, St. Seraphim of Sarov, and St. Agathon, so that they can be encouraged by these stories to do what God desires them to do. Sadly, throughout Christian history, Christians have done the opposite, showing an extreme lack of concern for the world they live in. They think they can ignore their calling and exploit the earth because the world is going to come to an end, and so what they do does not matter. This is an anti-Christian, that is, Gnostic, sentiment, encouraging Christians to dishonor God and God’s intention for the earth, as they end up continuing the way of fallen humanity and its destructive, nihilistic way of being.

We must truly embrace all life, not just human life, and that means we must be respectful of the environment and its needs, taking care of all life on the earth:

To be life-centered is to be respectful both of life and environment. As a way of looking at the world, biocentrism is an antidote to that human-centeredness that sees humans as the measure of all things and that believes humans, and humans alone, are worthy of our moral regard. Inasmuch as human beings are members of the family of terrestrial life, and perhaps even its most precious members, life-centeredness involves a deep and abiding commitment to their wellbeing. [2]

Sadly, many Christians have come to believe only humanity is important. They follow, as Laura Hobgood-Oster said, a kind of narcissism, one which has been extremely prevalent the last few centuries:

Yet in the last several hundred years Christianity has been hesitant, at times, to include animals in either its ethical or its theological systems. Without addressing the issue of “the animal,” Christianity not only lives in a potentially dangerous bubble, but it risks becoming increasingly narcissistic and marginal to the world as we know it, and as we are making it. [3]

It is time to move beyond that narcissism and learn from Agathon, learn how to be good stewards of the earth, taking care not only of ourselves, but all life, realizing the good, indeed, the dignity found in all life. Agathon was able to dialogue with and come to agreements with the dragon, and other saints were known to make similar pacts with animals. If we try, we can do likewise, making relationships with all creatures. When we do so, we will find ourselves, as well as those animals we related to, made better, even as we will provide another example of the inherent dignity of all life in this fashion. But if we do not, if we try to selfishly look after ourselves alone, we will find, as with all such selfishness, we will get the opposite of what we seek, as we will fall further and further from grace , and risk creating, if we are not careful, our own private little hell.

[1] More Sayings of the Desert Fathers. An English Translation And Notes. Ed. John Wortley (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019; repr. 2023), 119 [“Sayings Preserved in Coptic”: C2].

[2] Jay B. McDaniel, Of God and Pelicans: A Theology of Reverence For Life (Louisville, KY: Westminster/John Knox Press, 1989), 14.

[3] Laura Hobgood-Oster, The Friends We Keep: Unleashing Christianity’s Compassion for Animals (Waco, Texas: Baylor University Press, 2010), 6.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook.

If you liked what you read, please consider sharing it with your friends and family!

N.B.: While I read comments to moderate them, I rarely respond to them. If I don’t respond to your comment directly, don’t assume I am unthankful for it. I appreciate it. But I want readers to feel free to ask questions, and hopefully, dialogue with each other. I have shared what I wanted to say, though some responses will get a brief reply by me, or, if I find it interesting and something I can engage fully, as the foundation for another post. I have had many posts inspired or improved upon thanks to my readers.