Today’s guest post comes from Kristin Caynor, Ph.D. student at Trinity College Bristol/University of Aberdeen, TCK from Thailand, and a global theological educator. For her full bio, see below.

In the previous post, I offered re-kin-ciliation as an alternative to the discourse around “reconciliation” more broadly. I explained that in re-kin-ciling thought, the original goodness and harmony of human relations are affirmed, but re-kin-ciliation looks back much further than colonialism, imperialism, or any form of oppression.

It does not imply that relations between groups like Native people and the U.S. government were at one point healthy. What it says is that relationships between human beings are fundamental and that the violence and oppression we perpetrate represent a profound loss and degradation of human glory.

So how does re-kin-ciliation deal with the realities of evil?

We Never Start with the Fall

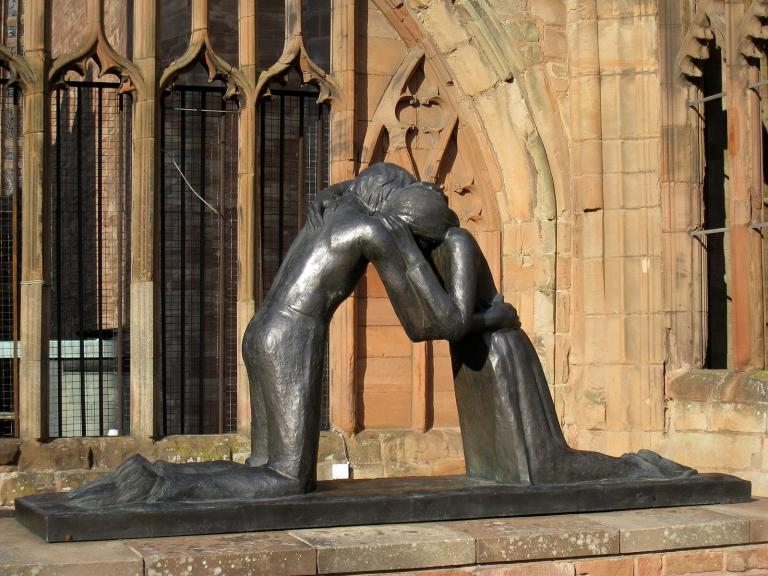

What taking re-kin-ciliation seriously causes us to do is not to dismiss evil, but rather to mourn it more deeply because of how far we have fallen. And while conversations about justice are so often dominated by shame and guilt, re-kin-ciliation affirms that no matter what we have suffered or what we have done, our story does not begin with brokenness, and it doesn’t need to end there either.

In my church community, our pastor always reminds us that we should never start the story of the world, ourselves, or others with the Fall. Rather, we need to start every story where it actually started: the created goodness spoken into being from a perfectly good God.

We constantly remind ourselves of this as we reach out to those experiencing homelessness and addiction in our streets, and we constantly remind them of it too. It isn’t only that you have the potential to be more than what you are now, but that your true self is actually more defined by the goodness God created than by the sin which has so harmed you and others through you.

The Western church tends to harp on Original Sin. But the biblical story starts with a creation that was good, and very good (Gen. 1:31). It is the perfection of God himself that is the very foundation of this world (John 1:3–5) and the very life force that continues to hold every atom together (Col. 1:15–18).

Listen to how John begins the story of the world:

“All things were made through him, and without him was not any thing made that was made. In him was life, and the life was the light of men. The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not overcome it” (John 1:3–5).

You see, if we begin the story of the world, ourselves, or our community with the Fall, we will be prone to preoccupy ourselves with the darkness. We may even be prone to see darkness as stronger than light, and sin as more significant and powerful over us than the power of God.

This is exactly how nearly every other creation myth begins, with chaos, oppression, and death, and that is just as true of our modern creation stories (“survival of the fittest”) as of our ancient ones.

The Story Begins with Joyful Response

But not the creation story of the LORD. His Story begins in a markedly different way: with speech, and with the joyous response of the cosmos in letting there be light. Elsewhere the Bible describes the delight that God took in his creative wisdom, and the joy with which wisdom herself responded over the inhabited world (Prov. 8:25–31).

As the story goes on, we see that the adam, the primordial human being, is also given the power of speech—not to create, but to co-create with God in the acts of naming, stewarding, and cultivating (Gen. 2:19).

Tragically, the first human pair departs from the unbroken litany of creation’s joyful responses to God’s speech. And every day since then has been marred by that tragedy, as history itself has twisted and contorted, and creation has groaned under the weight of corruption (Rom. 8:20–22). The fundamental kinship began to unravel as brother lifted hand against brother (Gen. 4:8), and rather than the multiplying kinship originally given to us (1:28), violence was multiplied (6:5, which uses the same word as 1:28).

But God the Word still holds all things together. He still lives, and he is still creating. He continued his creative acts by descending from heaven and joining his broken and beautiful creation here in the dust, in flesh and blood.

He came to show us that the story did not begin in brokenness, and it will not end there either. He came to restore and re-kin-cile us to his original goodness. The Alpha and the Omega came so that God would have the first word of creation, and so that he would also get the last.

Re-created by God’s Word

Every day we have opportunities to respond to God’s speech, to be re-created and re-kin-ciled with him and with each other, and to let there be Light in our lives that the darkness has not overcome. We can experience the power that raised Jesus from the dead living in us, and let God speak over us once again. And we can be healed.

But it doesn’t come from hearing the Word only.

In the next post, I will look at the “epistemology of re-kin-ciliation,” and explore how we can interpret scripture faithfully by living into re-kin-ciliation.

Kristin Caynor’s Bio

Kristin is a Ph.D. student at Trinity College Bristol/University of Aberdeen, and a global theological educator working with national and indigenous organizations and seminaries around the world through Live Global. She is an American with Hispanic background who grew up in both the U.S. and Thailand.

Her dissertation explores how hermeneutical practices themselves can foster relationships with others of difference, awareness of cultural diversity, reconciliation, and the inclusion of diverse cultural resources which may not yet have been considered in mainstream discourse. She is also a researcher for The Ephesians 2 Gospel Project, a global conversation around Eph. 2:11–22 exploring issues of collective identity conflict and shame-fueled violence from social scientific, theological, historical, cultural, and biblical perspectives.