By Northern Seminary student, Ben Davis. Ben begins his post about this book by talking about our connection, how he experienced typical recruitment by Northern professors (I have stories about other professors like this), and how that has altered the landscape of his life (and ours at Northern for every student influences every classroom), and how that provokes him to ask if God planned all that.

By Northern Seminary student, Ben Davis. Ben begins his post about this book by talking about our connection, how he experienced typical recruitment by Northern professors (I have stories about other professors like this), and how that has altered the landscape of his life (and ours at Northern for every student influences every classroom), and how that provokes him to ask if God planned all that.

A little over two years ago I had the opportunity to meet Scot McKnight. Scot was someone whose thought I had encountered through reading many of his books and his popular blog, Jesus Creed. Meeting him in person was meaningful for many reasons – and in the end it would prove fortuitous, as I’ll explain below. Our meeting had been occasioned by a residency program in Christian Spiritual Formation offered by a small college in my hometown. For years I had desired to go to seminary. I loved reading theology, biblical studies, and church history, and I thought a seminary education would suite my personality and already-acquired study habits well. But, circumstances being what they were – my wife had just discovered she was pregnant – and our finances strapped, going away to seminary was simply out of the question for me. The provision of this residency program, while not ideal, was the next best thing for me so I submitted my application and was accepted into the cohort. Shortly thereafter I was ecstatic to learn that Scot would be teaching in our first gathering on the nature of the gospel. I won’t bore you with the details of this time other than to say that my participation in the residency program afforded me the opportunity to have a handful of thoughtful conversations about books, theology, and everything Tom (N.T.) Wright. Through our conversations I was able to communicate my budding desire to go to seminary. He suggested that I look into Northern Seminary in Chicago, a place where he had been teaching for a few years. At that time, it would require me moving my growing family to Chicago, he said. After I explained my situation to him, we both agreed that moving for seminary was not likely the best decision. So, I left the idea alone and moved on, thinking little of it in the year to come

After that initial meeting, I kept in-touch through occasional emails, but I never mentioned seminary again. It would be an unrealized dream, I thought, so there was no point bringing it up. That is, until one day about eight months ago, I received an unexpected email from Scot asking if I was still interested in going to seminary. I replied, “yes, of course!” “But,” I added, “my situation hasn’t changed from the last time we spoke about it.” He then told me that Northern had unveiled a newly minted, state-of-the-art program designed specifically for distance learners. What’s more, he said, this program would be affordable and conducive for folks who had families and worked full-time. Astounded by his email, I talked it over with my wife, prayed, and submitted my application. Eight months later I can happily report that I am currently a student at Northern Seminary, pursuing a Masters of Arts in New Testament (MANT).

After that initial meeting, I kept in-touch through occasional emails, but I never mentioned seminary again. It would be an unrealized dream, I thought, so there was no point bringing it up. That is, until one day about eight months ago, I received an unexpected email from Scot asking if I was still interested in going to seminary. I replied, “yes, of course!” “But,” I added, “my situation hasn’t changed from the last time we spoke about it.” He then told me that Northern had unveiled a newly minted, state-of-the-art program designed specifically for distance learners. What’s more, he said, this program would be affordable and conducive for folks who had families and worked full-time. Astounded by his email, I talked it over with my wife, prayed, and submitted my application. Eight months later I can happily report that I am currently a student at Northern Seminary, pursuing a Masters of Arts in New Testament (MANT).

I’m telling you all this because I think my story illustrates an essential, if often misunderstood, theological idea: namely, it implicitly speaks about the providence of God. In this instance, God arranged circumstances in such a way that I was able to see my long-prayed-for desire of going to seminary become a present reality. God went before me, as it were, to chart a course by which I would arrive at the place I longed to be. Now, this begs an important question: If circumstances had been different, would I still be where I am? I don’t know. Counterfactuals are interesting to contemplate, but in the end they’re often little more than unhelpful speculations. If I had to guess, however, I think any number of different circumstances, occasions, and actions could’ve brought me to this place. What’s more, God could’ve aligned everything perfectly only to see me go a different direction entirely.

What I’m getting at is this. I don’t think God determined that I would go to seminary. Rather, his omniscience being what it is, God worked through secondary causes in the past to bring me to a set of options in the present that would in turn allow me to chose seminary or not. God paved the roads before me, in other words, but he enabled me to choose the one I was compelled to take – the back road or the Interstate. God gently nudges human action, he doesn’t coerce.

Many, however, see my situation differently. In their view, God is not guiding history to its ultimate end, intimately cooperating with humans for their good. Instead, God is controlling history moment-by-moment, leaving no room for human choices, good or bad. I’m sure you’ve heard it said, “God is in control.” While this little phrase is perhaps pastorally helpful, it lends undue credence to a larger idea that says God really is the one controlling every minute aspect of history, from the horrors of WWII to the seemingly negligible choice of which restaurant I’m taking my wife to for our weekly date night. Like Gepetto, the endearing puppet master who animated Pinocchio, God is pulling an intricate web of strings, tugging every human action toward his unsearchable, determined will. Conversely, I think it is better and more biblically responsible to say that “God is in charge.” This way of looking at things allows us to rest assured in God’s provision and fatherly care, while at the same time being chastened by the fact that our choices in life truly matter, not only to God, but to our neighbors as well. Humans are moral beings who invariably take the shape of that which they worship. Our decisions toward that end – wittingly and unwittingly – truly matter and should be taken seriously.

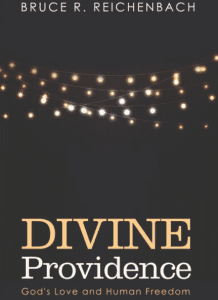

This brief, untutored meditation on God’s providence and human will is the circuitous route by which I want to arrive at the point of this post. For the question of God’s providence and human freedom is the stimulating subject of a new, undeniably important book by Bruce R. Reichenbach called, Divine Providence: God’s Love and Human Freedom. Reichenbach is a foremost philosopher of religion, who is Professor Emeritus at Augsburg College, where he taught philosophy for forty-three years. Thus he is a trusted guide on such matters, and his book will surely leave a significant mark on the fields of theology, philosophy, and philosophy of religion more generally.

As his subtitle intimates, Reichenbach puts forth the view that God cherishes human freedom and thus accommodates human choice under his providential care. Through his prodigious knowledge of Scripture, historical and systematic theology, and recent treatments in philosophical theology, Reichenbach sets before us the task of piecing together a complex puzzle: “The central topic of this book – divine providence – presents an intellectual and spiritual puzzle that is both magnetic and enigmatic.” He goes on to say, “Only the Puzzlemaker knows the finished masterpiece. We are thus limited to humanly determining how the joined pieces that we put together reasonably form a coherent picture.” That is, we are working with God’s revelation of himself – in Scripture and in nature – and the sharpest edge of human reason to better understand how God inexorably moves history to the fulfillment of his purposes while simultaneously accommodating human freedom, choice, and action to our own desired ends. A considerable undertaking, to be sure.

If, like me, you’re intrigued by this gargantuan topic, let this be your invitation. I want to take the next few weeks to examine the pieces of the complex puzzle as Reichenbach lays them out in front of us and I want to invite you to join me. Especially if you’re a pastor; this is a book you should read and a discussion you should be intimately aware of. Trust me: your people are thinking about this topic, and they’re looking to you for wisdom and sure-footed guidance along the way. I think this book will help you navigate the thicket. To close, I want to leave you with Reichenbach’s pastorally-wise words regarding the hope of God’s providence.

God acts in the world for our good, disciplines us to develop and grow in our moral and spiritual character, and ultimately patiently bids us to choose to enter into a personal, covenantal relationship with him. To make this possible God created us with significant freedom. Without significant freedom we can neither develop the qualities of character and spiritual maturity that enrich us as moral people, enter into a meaningful personal relationship with God and others in the human community, nor engage morally with our threatened and threatening environment. God does not force us to accept his providence, but lures, persuades, invites, seduces, and entices us to willingly accept him and his acts of goodness – the kingdom banquet – on our behalf. God is gracious, although at times the Lord of Severe Mercy. Providence is the theological way of talking about the ways in which God manifests his gracious love in our lives.

I’ll see you next week.

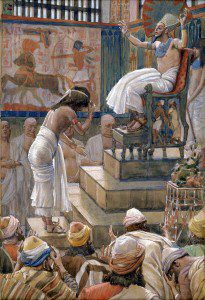

It has been awhile since the last post on Genesis, but it is time to step back and wrap up the story with the Joseph narrative, chapters 37, 39-50. The story is well known – long a Sunday School and sermon favorite.I brings the narrative of Genesis from the patriarchs to the opening situation in Exodus. The sons of Jacob move to Egypt where they become the people of Israel under bondage and in need of deliverance.

It has been awhile since the last post on Genesis, but it is time to step back and wrap up the story with the Joseph narrative, chapters 37, 39-50. The story is well known – long a Sunday School and sermon favorite.I brings the narrative of Genesis from the patriarchs to the opening situation in Exodus. The sons of Jacob move to Egypt where they become the people of Israel under bondage and in need of deliverance. Joseph’s Treatment of His Brothers. Both Bill Arnold (

Joseph’s Treatment of His Brothers. Both Bill Arnold (

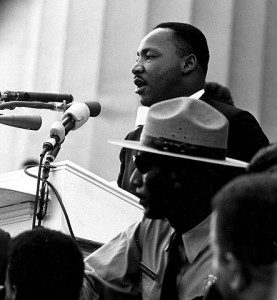

The second case study comes from Martin Luther King Jr. His argument for desegregation wasn’t based on a rational argument. It was based on a deeply moral argument. Human rights are only inalienable if they are real – endowed in the nature of the cosmos – rather than merely rational.

The second case study comes from Martin Luther King Jr. His argument for desegregation wasn’t based on a rational argument. It was based on a deeply moral argument. Human rights are only inalienable if they are real – endowed in the nature of the cosmos – rather than merely rational.

However, even if our moral convictions are the result of evolutionary pressure, this doesn’t make them objectively right or wrong. At best they were useful. Note, I didn’t say “are” useful. They brought us to the present, but they may be a hindrance rather than an asset moving forward. Keller makes this point – “Does the fact that this behavior was practical in the past constitute a moral obligation (not just a feeling) that we must do it now? Of course not.” (p. 182) We can also point to behaviors found in other species, especially other primates. Geladas, for example, (see

However, even if our moral convictions are the result of evolutionary pressure, this doesn’t make them objectively right or wrong. At best they were useful. Note, I didn’t say “are” useful. They brought us to the present, but they may be a hindrance rather than an asset moving forward. Keller makes this point – “Does the fact that this behavior was practical in the past constitute a moral obligation (not just a feeling) that we must do it now? Of course not.” (p. 182) We can also point to behaviors found in other species, especially other primates. Geladas, for example, (see