By Ruth Tucker

Here begins a three-part series on individuals—particularly historical figures—who have had a profound influence on me. Actually, this is a good exercise for all of us—to identify public figures who made a major difference in our lives.

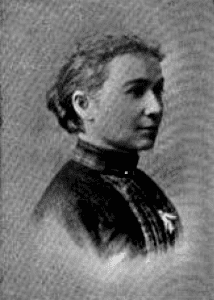

So I ask myself: What if A.B. Simpson (1843-1919) had continued his ministry as a very successful Canadian and American Presbyterian minister? What if? I often contemplate counterfactuals. Where would I be today without his conviction that his ministry must go in an entirely different direction? Were it not for him, there would not have been a Green Grove Christian and Missionary Alliance Church where I grew up in the faith.

So I ask myself: What if A.B. Simpson (1843-1919) had continued his ministry as a very successful Canadian and American Presbyterian minister? What if? I often contemplate counterfactuals. Where would I be today without his conviction that his ministry must go in an entirely different direction? Were it not for him, there would not have been a Green Grove Christian and Missionary Alliance Church where I grew up in the faith.

But before this white clapboard church had been constructed in a rural Wisconsin farming community 100 miles northeast of Minneapolis, Miss Cowan and Miss Salthammer arrived in the 1930s. They had been schooled at the Alliance Training Home, founded in 1916, three years before Simpson’s death. (Now Crown College, it was St. Paul Bible College when I enrolled in the fall of 1963.) They first announced a Sunday school, then church services. They evangelized, taught classes, preached sermons and were known for their daily deeds of mercy. When the church was on a solid footing, they moved on to other communities. They returned occasionally to teach vacation Bible school, and I remember thinking of them as odd ducks. But where would I be today were not for these two women preachers, often paid in sacks of potatoes or turnips, living and dying in poverty?

Where would I be were it not for A. B. Simpson? Though never a missionary himself, Simpson had an enormous influence on missions particularly on individuals who would go on to establish mission societies. The founders of both the Sudan Interior Mission and the Africa Inland Mission studied at his missionary training school and were deeply influenced by his passion for overseas evangelization. Likewise, several evangelical denominations were transformed into missionary sending agencies largely through his missionary zeal. Beginning in 1883, he orchestrated interdenominational conventions held in cities throughout the States and Canada, featuring missionaries from various denominations and mission societies. These conventions would lead to the formation of Simpson’s own international mission society, the Christian and Missionary Alliance. His footprint is very large indeed. I tell his story in From Jerusalem to Irian Jaya.

Born on Prince Edward Island in 1843, he was baptized by a Presbyterian missionary to the South Seas, John Geddie. Stories of missionaries filled his childhood. At Knox College in Toronto, missions continued to interest him, but after his graduation his reputation for preaching elicited a call to serve as pastor of the fashionable Knox Church in Hamilton, Ontario. After eight years Chestnut Street Presbyterian Church in Louisville came calling with an impressive yearly salary of $5,000. His wife, Margaret, was thrilled with the attention wealthy parishioners gave her, but her husband could only think of how “barren and withered” his ministry had become, but during a short stay in Chicago his life was transformed:

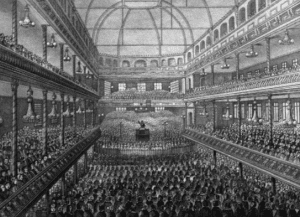

I was awakened one night from . . . a strange dream. . . . It seemed to me that I was in a vast auditorium, and millions of people were there sitting around me. All the Christians in the world seemed to be there, and on the platform was a great multitude of faces and forms. They seemed to be mostly Chinese. They were not speaking, but in mute anguish were wringing their hands, and their faces wore an expression that I can never forget. . . . I threw myself on my knees, and every fibre of my being answered, “Yes, Lord, I will go.”

He was determined to go to China, but for one obstacle—Margaret. She agreed to leave her beloved Canada to go to Louisville, but not to China. With six children, she had no interest in forsaking the comfortable lifestyle the Chestnut Street Church afforded them: “I was not then ready for such a sacrifice. I wrote him that it was all right—he might go to China himself—I would remain home and support and care for the children. I knew that would settle him for a while.”

Simpson was not a David Livingstone who simply abandoned his wife and children for mission work. But he was convinced that God was calling him “to labor for the world and the perishing heathen just the same as if [he] were permitted to go among them,” not, however, based in Louisville. So in 1879 he was determined to action was; he accepted a call from Thirteenth Street Presbyterian Church in New York City. Still he was restless, and after two years he resigned and launched a new ministry. It was an impulsive decision that stunned not only the church and his associates, but his wife Margaret. A. W. Tozer poignantly described her feelings:

The wife of a prophet has no easy road to travel. . . . From affluence and high social position she is called suddenly to poverty and near-ostracism. She must feed her large family somehow—and not one cent coming in. . . . Mr. Simpson had heard the Voice ordering him out, and he went without fear. His wife had heard nothing. . . . That she was a bit unsympathetic at times has been held against her by many. That she managed to keep within far sight of her absent-minded high soaring husband should be set down to her everlasting honor.

Starting out with seven committed followers, the movement grew quickly and rented facilities became too small. After moving from one larger place to another, the decision was made to erect a permanent building, the Gospel Tabernacle. He was determined to found a movement, not a denomination, but whatever it was it spread rapidly around the world. Within a decade he had commissioned more than a hundred missionaries to serve in more than a dozen countries. If the numbers sound impressive; the human toll was enormous. In the Congo and Sudan, deadly diseases and climate “exacted such an awful toll of lives,” writes A.E. Thompson, “that for years the missionary graves in both fields outnumbered the living missionaries.” In China the situation was also grim. The Boxer Uprising of 1900 claimed the lives of thirty-five Alliance missionaries and children.

A.B. Simpson. If it were not for him, would I have ever become a professor in the fields of missions and church history? Would I have been launched into a writing career with From Jerusalem to Irian Jaya: A Biographical History of Christian Missions?

That book ends with a personal reflection. I tell about growing up in the 1950s in a farming community in northern Wisconsin and attending a little country church, where it was difficult to go through teenage years without getting a “call” to overseas missions. In most cases the sense of calling was quickly forgotten when other “calls” interfered. But for me and my younger cousin Valerie, it was different. I write in third person:

They attended the same schools and the same little country church. Valerie too felt called to foreign missions. She, too enrolled at the St. Paul Bible College to prepare for her life’s calling. And she, too, longed for marriage and family. But her sense of calling to the foreign field came first. Valerie graduated from Bible college and soon thereafter bade farewell to her family and loved ones and set out alone for Ecuador, where she continues to serve today [now retired] with the Christian and Missionary Alliance.

Two young women whose lives paralleled each other’s in so many respects. Two young women who felt called to foreign missions. Valerie went. I stayed home.

For years when I was traveling and lecturing on missions, I would often end with this story. Students would come up to me and want to hug me and tell me it was okay—that I shouldn’t feel guilty. I actually didn’t feel guilty. In fact, I often think the “mission field” was better off without me. But that “call” made an incredible difference in my life, and I would not be where I am today without it—and without A. B. Simpson, founder of the Christian and Missionary Alliance.

A footnote: Valerie retired two years ago, and some months later I received an invitation to her wedding. John and I traveled back home to northern Wisconsin to witness her marriage to a widowed Alliance missionary. It was a glorious celebration and a wonderful time for me to renew old friendships I had made nearly a half century earlier at the now shuttered Green Grove Alliance Church.