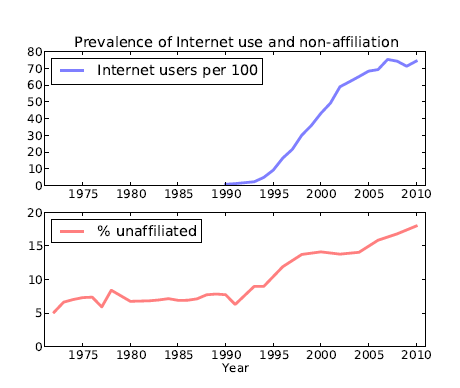

Since the early 1990s, there has been a significant uptick in Americans abandoning their faith. After crunching the numbers, one researcher says contributing factors such as upbringing and education only explain part of the increase. What about the rest?

After controlling for variables like income, environment, and so on, computer scientist Allen Downey of Olin College of Engineering in Massachusetts found 25 percent of the decline can be correlated with Internet access. More Web, less faith.

Why? Here’s Downey’s stab at an answer: “For people living in homogeneous communities, the Internet provides opportunities to find information about people of other religions (and none), and to interact with them personally.” So increased exposure leads to doubt, disagreement, disenchantment, and ultimately to discarding your faith.

Maybe, but I don’t buy it. Downey’s answer plays off the modernist prejudice that equates religion and ignorance. That’s false on its face. But once we consider the Internet as a factor at all, there’s a far more obvious answer than wider horizons: porn.

Porn has been part of the Web from day one. And the stats for online consumption are staggering, even among Christians.

Disaffiliation should come as no surprise. We’ve already seen that porn makes prayer and beneficial contemplation impossible. Given the Christian understanding of the spiritual life, we’re not capable of simultaneously pursuing our lusts and sanctification. Such a pursuit causes internal dissonance, and the only resolution involves eventually conceding to the pull of one or the other. (I’ve talked about that before here.)

Personal testimony adds to the picture. In his book Samson and the Pirate Monks, Nate Larkin discusses his battle with sexual sin and its effect on his state of belief. The deeper he got the further away he felt from God.

I often screamed at God, banging on the steering wheel and begging him to relieve me of this terrible wickedness, to take the urge away, but the heavens were silent. After a while, I started wondering whether God was listening, whether he cared about me anymore, or whether he even existed at all.

On the flip side, as Larkin turned from lust, his faith returned. “I came to believe the gospel a little more,” he says. “The most powerful proof of God’s existence was the transformation that was taking place in my character.”

Faith is obedience, and obedience is faith.

If the rise of the internet has anything to do with a loss of faith — and it’s an interesting thought — the role of ideas is likely minimal. Arguments don’t cool many hearts, but sin surely does.