There’s a broad swath of Christian thought out there that runs like this: “I’m a Christian.” (Or, lately, the more common, hipper-seeming, ‘I’m a follower of Christ.’) Being a follower of Christ means that I am filled with the Holy Spirit of God. That means that I am content, peaceful, joyous. So if I feel anger, frustration, or sadness, it can only mean that something has gone terribly wrong with my relationship with Christ.”

There’s a broad swath of Christian thought out there that runs like this: “I’m a Christian.” (Or, lately, the more common, hipper-seeming, ‘I’m a follower of Christ.’) Being a follower of Christ means that I am filled with the Holy Spirit of God. That means that I am content, peaceful, joyous. So if I feel anger, frustration, or sadness, it can only mean that something has gone terribly wrong with my relationship with Christ.”

And that’s how we end up with Christians who feel that having “bad emotions” means that they’re not quite the Christians they should be.

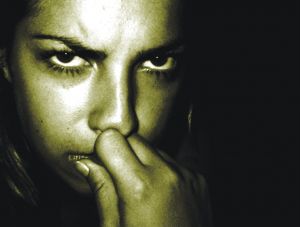

It’s vital for anyone, Christian or not, to understand that there is no such thing as a “bad” emotion. Such a thing simply does not exist. Virtually all emotions are good, insofar as every emotion any person ever has is meant to tell that person something it would be tremendously beneficial for them to understand. That’s what emotions are for. Communicating important information about what’s going on in your heart, mind, and life is what emotions are supposed to do. “Bad” or negative emotions arise to show you something — to inform, explain, teach, point you to a place where you need to go in order to learn something important about yourself.

A “bad” emotion is like an air-raid siren. Its harsh shrillness is painful to experience — but it’s very pointedly telling you that you need to do something in order to remain balanced and healthy.

The only thing that can render a strong emotion “bad” is if you ignore or invalidate it, out of believing that someone like the person whom you want to be (or, worse, like the person whom you want others to think you are) wouldn’t or shouldn’t have such an emotion. Then you’ve got a problem. Because then not only have you ignored whatever it was that your “bad” emotion was trying to alert you to, but, in a larger sense, you’ve empowered a lie about yourself. You’ve traded the truth of who you are for a lie about whom you think you should be. You’ve ignored a problem your heart was trying to tell you about. By insisting that something real isn’t real, you’ve lied. It’s that simple — and it’s that problematic. Every time you determinedly align yourself with that which counts form more important than substance, you take one more step down a path that can only grow darker and more dangerous.

So the next time you have a “negative” emotion, take care not to resist or fight it. Don’t immediately attach to it the idea that it’s proof you’ve stepped outside the light of God. Instead, think of it as a means by which you can move closer to God. Because that’s exactly what it is.

Instead of telling that “bad” emotion what it is, let it tell you what it is. Stay with it. Make it talk to you. Let it open itself up, and reveal to you what it’s really made of, where it really comes from, what really caused it. A “bad” emotion means there’s a very real problem — and it necessarily contains within itself the solution to that problem. But you don’t get the knowledge that a “bad” emotion has to offer you for free. You have to work for that knowledge. And the working part is where, instead of dismissing or trying to scoot around your troubling emotion, you delve into it.

One day maybe fifteen years ago I was feeling angry, because my wife wanted to talk to me about our money. The moment she mentioned our household budget, I felt myself tense up. But instead of trying to suppress or ignore that negative emotion, I focused long and hard upon it. And through that — through basically allowing myself to feel all of that negative emotion, instead of just the tip of it that I had sort of immediately registered as anger — I realized something of which I’d never before been consciously aware, which is that my father was afraid of the world; he was afraid of life, really. So he always resolutely refused to participate with my mother in the management of our family’s financial assets, because at a deep level he felt certain that doing so would provide him objective, real-life proof that he had nowhere near the assets he needed to protect himself or his family. But the truth was he had all kinds of money. It was in fact his fear of not having enough money that drove him to make the great amounts of it he did. But he could never quite make enough to alleviate his fear of not having enough.

My father wasn’t really afraid of not having enough money; objectively, he certainly did. What he was truly afraid of was the world generally.

And from him I had inherited that abiding fear. And—on that day, on that morning with my wife—that fear had manifested itself in my angrily resisting my wife’s attempt to force me to face the “proof” that, just like my dad before me, I was incapable of financially protecting myself and my family from the harsh vagaries of the world.

And the sheer force of realizing that that was the loop I was caught in was enough for me to break it. Suddenly, I was free of my father’s weirdness about money. From that moment on I was able to be more realistic about not just my money, but about the world at large.

And I got all that benefit from doing nothing more dramatic than basically facing down one “bad” emotion.

Our “bad” emotions aren’t fleeting things of no enduring validity or substance. They’re a primary means by which, in terms exactly tailored to us, God very directly points us toward truths we could use to become more peaceful and content in this world.