The following post is from Laura Statesir, Director of Family and Youth at The Marin Foundation.

A while ago my fiancée and I attended a Christmas party at a friend’s house. We stuffed ourselves with holiday themed snacks and drinks and chatted with the other guests. Our friend’s parents were there and we talked with them as well. A good time was had by all…

A while ago my fiancée and I attended a Christmas party at a friend’s house. We stuffed ourselves with holiday themed snacks and drinks and chatted with the other guests. Our friend’s parents were there and we talked with them as well. A good time was had by all…

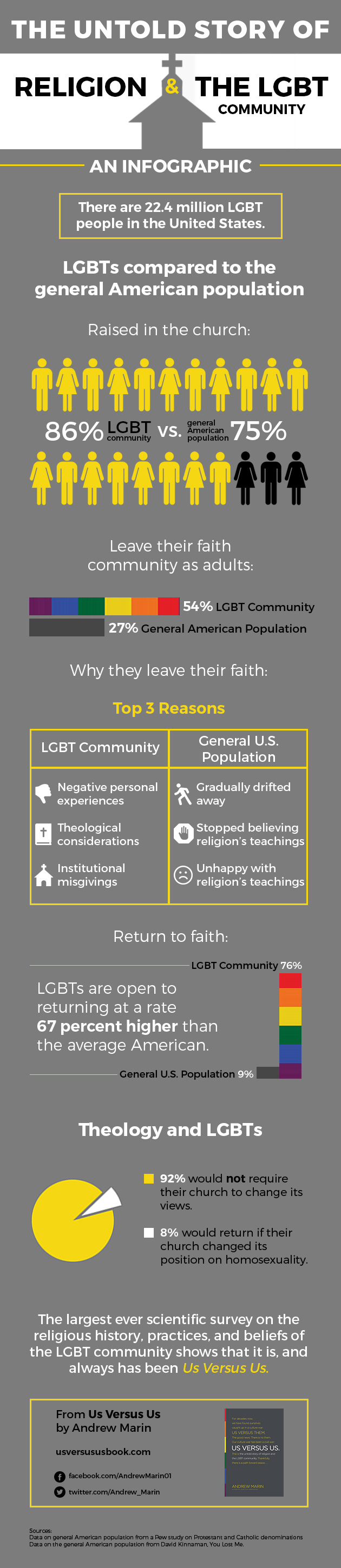

A few weeks later our friend told us how glad she was we had been at that party and spoken with her parents. It turns out that her father, who didn’t have the most loving perspective of the LGBTQ community, was greatly impacted by getting to know and observing me and my fiancée. Apparently hearing about our lives and watching how we care for one another helped to change some beliefs that her father held about gay people.

So this is great right? It’s wonderful that another person’s attitudes have been challenged by meeting a LGBTQ Christian person. Frankly all I remember discussing with my friend’s father was sports but I am always incredibly grateful anytime the Lord moves in people’s hearts. I am glad my fiancée and I represented ourselves and our love in a positive light.

BUT…

What if I had been having a bad day? I can be quite shy and sometimes I just don’t feel like explaining myself to new people – so what if I had ignored my friend’s father? What if my fiancée and I had been arguing or experiencing a tense moment in our relationship? Would my friend’s father have walked away with the same positive changes in his viewpoint or would we have confirmed every negative opinion he believed about LGBTQ people?

I live in fear of screwing up. If I mess up it’s not “Laura did something wrong”, it’s “that lesbian Christian woman did something wrong,” most likely followed by an “I told you so.” If I don’t represent myself as a gay Christian in a favorable light then my conduct could damage someone’s idea of what a gay Christian looks like. I don’t mean to sound pompous or self-important, but it seems like my actions have the power to either confirm or confront stereotypes and therefore affect LGBTQ Christians’ chances of being accepted, respected, and included.

I have still spent much of my life outside of the majority. In college I was one of the only females in a student military organization known as the Corps of Cadets. Later, as an instructor for a wilderness therapy program that worked with adjudicated youth, I was one of the only Christian staff members. Then for five years I lived and worked in the Dominican Republic and was one of few foreigners. But none of those experiences prepared me for my journey as a LGBTQ Christian.

In all of these experiences I had never truly felt such an imperative and momentous weight in representing a minority until I came out as a gay Christian. LGBTQ people are a minority in our country and LGBTQ Christians are an even smaller part of that larger gay community.

Being a gay Christian there is an immense pressure to always do the right thing and always provide the best example. If I do something well I prove the validity of our existence. I show people you can be gay and still love and serve Jesus. My behavior could help break down negative stereotypes and create more grace-filled interactions. What an incredible honor and what a heavy, heavy burden.

Even in my upcoming marriage I feel this same pressure to represent gay Christians well. (As if any marriage needs more pressure to succeed.) I love my fiancée with all my heart and plan to stay committed to her for life, but what if our marriage didn’t last? What message would that give to those who disagree with same-sex marriages? That same-sex marriages won’t last because they aren’t blessed by God? (Because straight marriages NEVER end in divorce, right?) And what if we had kids and for whatever reason one of our kids turned out to be LGBTQ or not a believer? What would that say to those who think LGBTQ people should not be parents?

It is an unjust burden that LGBTQ Christians have to be on their best behavior; that we are not allowed to be human because we must be more than. On a personal level, feeling such responsibility has at times made me bitter or feel like I’m putting on a show. In trying to show the world that not all gay people are heavy drinkers and drug users, for example, I should be allowed to have a glass of wine. In trying to show the world that not all gay people are promiscuous, I should be allowed to have relationships that fail. In trying to show the world that not all gay people are atheists I should be allowed to ask questions and express my doubts.

So on behalf of my LGBTQ brothers and sisters in Christ, I ask that you do not force us onto a pedestal. Do not judge or form opinions about our entire community based on your experiences with one person. Allow us to be human, to make mistakes, to err. Allow us to be who we truly are (including the messy parts), and extend to us the same grace that Christ has extended to you in your own life.