Some weeks ago I read an article about a man who shot a home invader in the back as she fled down an alley, having already left the house. In the comments, readers pointed out that the woman had chosen to break into the guy’s home, and that when he returned and found her there she initially assaulted him, and that she therefore deserved what she got. These things were ostensibly true, but here’s the thing—they had no bearing on whether or not the man had been correct to shoot and kill her.

We don’t give out the death sentence for breaking and entering. We don’t even give out the death penalty for assault. We usually reserve the death penalty for murderers—a life for a life, the reasoning goes. Or at least, I thought we did.

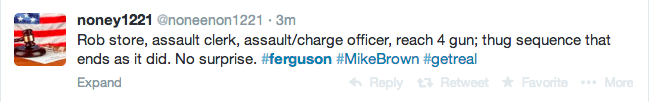

All of this has come to my mind again lately in all the discussion of Mike Brown and Ferguson. I’ve seen quite a number of reactions that look something like this:

Now obviously, most of this is in dispute, and it is highly unlikely that this version of the story is true in total (especially the last part). But let’s imagine that the first part was true, that Mike Brown did steal those cigars. Would that merit the death penalty? Do we kill people for stealing cigars now? Is that the kind of country we want to live in? I thought we found Saudi Arabia practice of chopping off people’s hands for theft barbaric? Or am I suddenly out of step with mainstream American thought here?

Now yes, if someone has a gun that changes the situation. They become a threat, and taking a life in self defense is generally considered acceptable. But this is not what we’re talking about here.

Back when Trayvon Martin was ion the front pages, there was much discussion of previous suspensions for marijuana use. But does marijuana use warrant the death sentence? Was Zimmerman allowed to kill Trayvon because Trayvon had been suspended from school and smoked pot? Trayvon didn’t have a gun, he was out to buy iced tea and skittles. But do you have any idea how many people defended Zimmerman on the basis of Trayvon’s suspensions and pot smoking, and even talked about how Zimmerman had bettered the world by getting rid of one more “thug”?

So many times we are told that the person killed—whether Trayvon or Mike Brown or one of the many others—was a “thug.” They smoked pot, they had a criminal record, and so forth, as though these things somehow justify extrajudicial murders.

As far as I can see, the only time killing someone is justified outside of capital punishment or war (and even those two get iffy for me) is self defense. But self defense has to involve actual immanent danger. Shooting someone in the back as they run from you, or put their hands in the air—that is not self defense. (And following someone around until they feel unsafe and turn around to defend themselves, and then shooting them in self defense is some serious messed up shit, if you’re asking me.) We need to get straight about what we mean when we say “self defense,” because even I’m not sure anymore.

I’m not the first person to say any of this, of course.

But the other problem is the terms of the debate itself. Whether or not Martin was a good kid or a bad kid, an angel or a thug, a normal teenager or a dangerous deviant, he had every right to walk in the streets of his soon-to-be-stepmother’s neighborhood without fear of being shot. A criminal record, a manner of dress, a height: none of these make the shooting of an unarmed, law-abiding teenager justified. And yet here we are, forced to defend Martin’s honor, as though if he had been a gangster there’d be nothing to say. As though the minute a black man is anything but a choir boy it’s okay to shoot him in the street.

By all accounts, Brown was One Of The Good Ones. But laying all this out, explaining all the ways in which he didn’t deserve to die like a dog in the street, is in itself disgraceful. Arguing whether Brown was a good kid or not is functionally arguing over whether he specifically deserved to die, a way of acknowledging that some black men ought to be executed.

To even acknowledge this line of debate is to start a larger argument about the worth, the very personhood, of a black man in America. It’s to engage in a cost-benefit analysis, weigh probabilities, and gauge the precise odds that Brown’s life was worth nothing against the threat he posed to the life of the man who killed him. It’s to deny that there are structural reasons why Brown was shot dead while James Eagan Holmes—who on July 20, 2012, walked into a movie theater and fired rounds into an audience, killing 12 and wounding 70 more—was taken alive.

Can we stop pretending that some people deserve to be executed, without trial? Can we try to remember that we don’t sentence people to death smoking pot, or committing burglary, or stealing cigars? This conversation has got to change.