The way evangelicals approach mental health problems has often been ineffective and unhelpful. The evangelical approach to these issues, however, is not monolithic. (In fact, amazingly, Focus on the Family treats depression seriously and presents medication as an effective solution.) But two strains of thought present in many evangelical churches can keep individuals from seeking diagnosis or getting treatment. The first treats mental health problems as failures of faith—the fault of the individual.

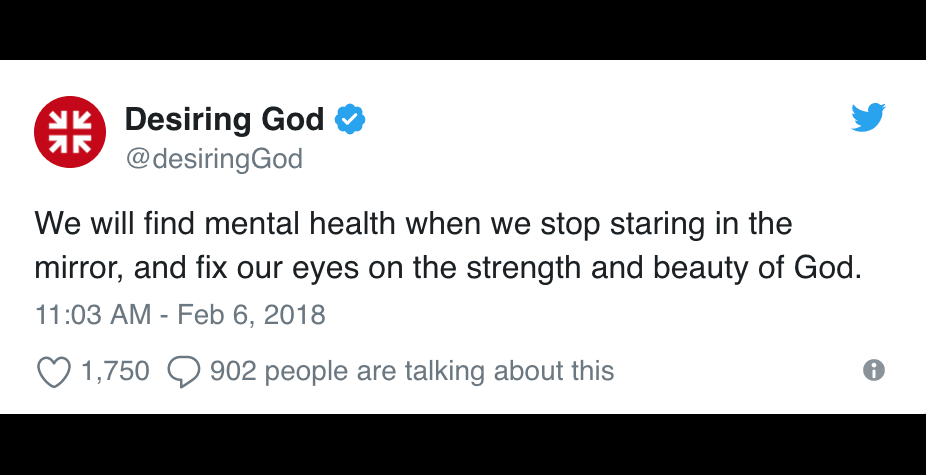

Have a look at this tweet by influential evangelical theologian John Piper:

Text: “We will find mental health when we stop staring in the mirror, and fix our eyes on the strength and beauty of God.”

The other belief present in many evangelical churches holds that happiness is not something that we should seek in and of itself. This is the root of Piper’s mention of staring in the mirror—the idea that caring about our mental health (rather than focusing on God) is self-centered and selfish—but it is also different. Piper suggests that if we would stop focusing on the mirror and start focusing on God, our mental health problems will go away. But in a post this month in Christianity Today titled Blessed Are the Unsatisfied, evangelical author Amy Simpson suggests that maybe we may not be meant to be happy.

“We often assume that loneliness and dissatisfaction are symptoms of spiritual failure,” Simpson writes, echoing Piper’s tweet. “But what if they’re signs of healthy faith?” As she explains:

While most Christians freely embrace the idea that the world doesn’t satisfy, many believe the remedy is to find contentment in a relationship with Christ. As long as we are in relationship with Jesus, he will fill that “God-shaped hole” inside us, and once that hole is filled, we will no longer ache with desire or longing.

The trouble is, while knowing and following Jesus has its priceless rewards and eventually leads to fulfillment, it won’t fully deliver on this promise now. Sometimes obedience makes a person miserable. Sometimes it leads to suffering or even death. Yes, a relationship with God can bring comfort, peace, and even joy in hard circumstances. But it may not bring satisfaction or happiness—at least in complete and lasting form.

A believer’s faith, Simpson writes, may not be enough to satisfy them. Lack of satisfaction with life, she argues, may not be a spiritual problem at all. For those evangelicals who may may have been taught to blame themselves for their own depression or other mental health problems, this is a helpful message. But there’s a problem.

Have a look at this bit here:

In other words, maybe we don’t feel truly satisfied because we aren’t. Maybe God doesn’t want to take away our longings yet. When we grow deeper in faith and closer to Jesus, we’re likely to find ourselves less—not more—satisfied with life here and now.

Scripture gives us evidence of these truths.

Consider just a few of the Old Testament prophets. On the heels of his great victory over the prophets of Baal on Mount Carmel, Elijah ran for his life, became depressed and suicidal, and complained to God (inaccurately) that he was the only faithful prophet left alive.

And then there’s this:

What about Jesus himself? Was he satisfied by his life in this world? “He was despised and rejected by mankind, a man of suffering, and familiar with pain” (Isa. 53:3). He wept over Jerusalem, matter-of-factly told a potential follower that following him would be no picnic, and lost his temper over corruption in the temple. When he faced death by crucifixion, he spent the night in prayer and told his disciples, “My soul is overwhelmed with sorrow to the point of death.”

Of course, we cannot experience what Jesus experienced. We’ll never understand what it meant for him to don human form with its limitations, pains, and sorrows. But like Jesus, we should be uncomfortable here. We should be unsatisfied by what we experience in this life. We were made for another world, and God wants his people to long for it.

Do you see what’s missing here? There’s no suggestion that depression or suicidality should be treated. Instead, there’s an assumption that being unsatisfied with life and unfulfilled—and depressed or suicidal—is to be expected in this world. It’s just how it is, and it won’t change until we reach the next world—life after death. It should be unsurprising that that message would tend away from treatment and medication.

While I’m glad that there are some evangelicals who support the diagnosis and treatment of mental health issues—and there are—evangelical luminaries like John Piper and Christianity Today are still promoting ideas that present mental health issues as a personal failure or as something to simply suffer through. These two very different answers to the problem of being unhappy or depressed—“you’re just not focusing enough on God” and “you’re not supposed to be happy”—are equally unhelpful (and even dangerous).

I have a Patreon! Please support my writing!