I grew up in a family influenced by the Quiverfull movement. Think the Duggars, except that most families didn’t make it quite that far—either in terms of the number of children or the whole TV show thing. Still, in this community having large numbers of children was glorified as particularly godly. I attended homeschool conventions where the attendee with the largest number of children would be singled out and given a prize. The best gift you could give your children, it was said, was another sibling.

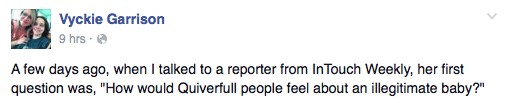

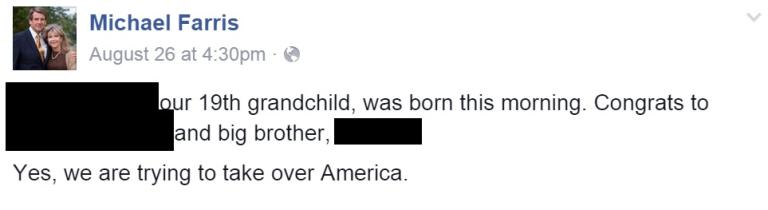

All of this means that I have some pretty big feelings when reading things like this:

In 2015, the National Bureau of Economic Research published a research review discussing how growing up in a large family affects children. The research revealed that there is a trade-off—when the quantity of children in a family increases, the quality of the experience decreases.

Or this:

One of the most notable challenges the researchers found was parental involvement with children. When the family grows, it makes sense that the mother’s attention splits. Researchers also noted decreased cognitive performance in children of larger families, as well as a notable increase in behavioral challenges.

Before I look at the study’s findings—which I will do in a moment—I want to include one anecdote from the above article. This article, published in Healthy Way, uses researchers’ findings as the backdrop for a number of individual interviews, including one with a woman who grew up as the middle child in a family with seven children:

“…I’m the middle [child] of seven,” Rebecca Gebhardt tells HealthyWay about her family. “As a child, there was always a lot going on, there was never a ton of money … but we didn’t know any different.”

Gebhardt says it was a busy childhood, but the memory that sticks out to her is eating every meal together, even if those meals only lasted a few minutes. She says that practice brought her family together.

As for the negative impact of being the child of a large family, she says the most notable thing was the competition between siblings—a dynamic that remains today when everyone gets back together for holidays.

I was the oldest child in a family larger than Gebhardt’s, and I feel what she says here intensely. I enjoyed eating every meal together—the happy chaos—making up games with my siblings, always having someone there to play with. But it wasn’t all fun and games. People often remark that it must be nice to have so many siblings now, and it is, but we don’t always all get along. Sometimes we don’t get along as well. It can feel like having our own family soap opera.

Now let’s turn to the study itself:

[W]e find that families face a substantial quantity-quality trade-off: increases in family size decrease parental investment, decrease childhood cognitive abilities, and increase behavioral problems.

This is the overall finding—the larger the family, the greater the decreases in parental investments, and, along with that, the greater the decreases in children’s cognitive ability and increases in children’s behavioral problems.

At issue, researchers found, was time:

When we decompose parental investments into time, resources, affection, and house safety, we find time to be the most critical input that decreases with additional children.

And:

[A]n additional sibling reduces the HOME score – the NLSY’s measure of parental investment in a child – by 1.7 percentile points. This finding speaks directly to the trade-offs in a quantity-quality model of child rearing. Parents in larger families reduce their per-child investment.

This finding is unsurprising. Having more children means the parents’ time will be more divided. I knew that growing up. The argument was that other things—having siblings to spend time with—offset it, that parents could still purpose to spend one-on-one time with their children, and that spending time with children together as a group was valuable too.

There was also a strain of thought that held that parental involvement is overvalued. Parents shouldn’t strive to be their children’s friends, the reasoning went. Children needed responsibility, and hard work, not parents fawning over them. Parents should train their children, and spend time working alongside them—the sort of work that must be done in every large household—and that would be sufficient.

The researchers findings regarding cognitive effects suggest that the above explanations and justification are inadequate. I’ve known for some time that second children tend to underscore first children—that there’s something about that one-on-one parental involvement in a child’s early years that’s important. This study points to more than that. It suggests that the birth of each additional child actually decreases the cognitive abilities of each older child.

The researchers found that:

[A]n extra sibling reduces an older sibling’s cognitive score by 2.6 percentile points.

This is a small effect—a tenth of a standard deviation—but it is an effect that is present nonetheless. On finding this, the researchers wondered whether this was only the result of temporary disruption caused by the new sibling’s birth. So they checked, and they found that the effect is not temporary.

Test scores and parental investments are both worse over the longer horizon than in the short run. Only in behavioral problems do we find that the effects may dissipate over the longer run.

Furthermore, researchers found a difference based on gender:

The effects on cognitive scores are small and insignificant for boys. They are large and significant for girls. In contrast, the family size effect is larger for boys for “Behavioral Problems.”

This finding should have a glaring red flashing neon light over it.

In larger than average families, the added burdens of childcare and housework falls disproportionately on the girls. Is this the reason for the greater cognitive effect on girls? Are girls in large families disproportionately asked to sacrifice time they could be spending on school or extracurriculars, to their own detriment?

One last thing. Researchers found that while there are cognitive effects throughout, the cognitive effects were greatest in children whose mothers had low AFQT scores. The Armed Forces Qualification Test (AFQT) is an armed forces recruitment test that measures paragraph comprehension, word knowledge, mathematics knowledge, and arithmetic reasoning. In other words, when a mother has a higher education level, some of these effects are offset, but when a mother has a lower education level, these effects are intensified (this holds true across racial lines).

This makes me think about the way girls’ education is treated in Quiverfull circles. I went to college, as did many if the girls I grew up with—but not all did. There was a strain of thought in the Quiverfull movement that held that college was unnecessary or even harmful for girls. Girls were to be wives and mothers, to bear and raise large families themselves—college exposed girls to worldly ideas, threw them in with bad company, and gave them ideas. One woman in our community told my mother that sending me to college would “ruin me” for ever being a good wife and mother.

As I sit here I can’t believe how obvious this all is—even short of having a large family, children’s educational attainment often mirrors that of their mother. Why was a woman attending college not seen as something that would be a benefit to her children, in Quiverfull circles? Perhaps because it is not possible to increase a girl’s education without giving her ideas.

What a mess.

Beyond just this, these circles came with a devaluing of education and educational attainment in general. What was important was not how much you knew, but who you knew—whether you knew Jesus as your personal savior. We’re preparing our children for heaven, not Harvard, parents used to say. College gives children ideas—in some families and communities, opposition to college attendance applied not to daughters only, but also to sons.

In this context, any finding that having a large family might lower children’s cognitive scores is unimportant. That having a large family will (ostensibly) teach children responsibility and denial of self is far more important.

I have a Patreon! Please support my writing!