Answers in Genesis recently posted an article titled Were Dragons Real? written by Bodie Hodge, an Answers in Genesis speaker who has his master’s degree in mechanical engineering. Hodge begins by explaining that after dodos went extinct, many people thought the very existence of the dodo was an invention—until fossils and other specimens were found and brought to light.

[W]e have descriptions, drawings, and accounts of dragons—not just in handfuls like we have of the dodo, but in massive numbers from all over the world! And many of these descriptions and accounts are very similar to creatures known by a different name: dinosaurs.

First of all, the accounts we had of the dodos were first hand and recent—they came from sailors who had seen them, not from myths that were hundreds or thousands of years old. This isn’t to say that sailors’ eyewitness testimony is always right, of course—unless we are to believe mermaids are real. But there’s a very clear difference between sailors claiming to have seen something in a specific area in the recent past, on the one hand, and ancient myths and legends, on the other.

But let’s talk about mermaids! Because you know what? Like dragons, mermaids exist in mythology around the world! Does that mean mermaids are real? Very serious question! If the ubiquity of dragon myths suggests that there was such a thing—which is in fact appears to be what Hodge is arguing—then the ubiquity of mermaid myths ought to be taken very seriously. Right?

Hodge would probably contend that the difference is that we have dinosaur bones and know these creatures once existed, and dragons closely resemble these creatures—ergo, dragons were dinosaurs that existed in living memory! This is an important win for young earth creationists, who make a connection between dragons and dinosaurs in order to argue that there was a time within human memory when humans and dinosaurs coexisted. Take that, evolutionists!

Of course, there are some problems with this claim.

But first, let’s return to Hodge:

Dragons by Ancient Historians, Literature, and Classic Commentaries

Dragons were viewed as real creatures by virtually all ancient writers who commented on them. While many references could be cited, consider these select accounts:

- “But according to accounts from Phrygia there are Drakones in Phrygia too, and these grow to a length of sixty feet.” [Aelian]

- “Africa produces elephants, but it is India that produces the largest, as well as the dragon.” [Pliny]

- “Even the Egyptians, whom we laugh at, deified animals solely on the score of some utility which they derived from them; for instance, the ibis, being a tall bird with stiff legs and a long horny beak, destroys a great quantity of snakes: it protects Egypt from plague, by killing and eating the flying serpents that are brought from the Libyan desert by the south west wind, and so preventing them from harming the natives by their bite while alive and their stench when dead.” [Marcus Tullius Cicero]

- “Among Egyptian birds, the variety of which is countless, the ibis is sacred, harmless, and beloved for the reason that by carrying the eggs of serpents to its nestlings for food it destroys and makes fewer of those destructive pests. These same birds meet winged armies of snakes which issue from the marches of Arabia, producing deadly poisons, before they leave their own lands.” [Ammianus Marcellius]

- Gilgamesh, hero of an ancient Babylonian epic, killed a huge dragon named Khumbaba in a cedar forest.

- The epic Anglo-Saxon poem Beowulf (ca. a.d. 495–583) tells how the title character of Scandinavia killed a monster named Grendel and its supposed mother, as well as a fiery flying serpent.

- “The dragon, when it eats fruit, swallows endive-juice; it has been seen in the act.” [Aristotle]

Ancient historians and writers clearly believed creatures like dragons were real. They describe seeing them first hand — often in the context of other types of animals that still live today. Some historians even describe the fiery flying serpents as real creatures in regions near where Moses and Isaiah were and point out the winged nature of these flying serpents. Such things are a great confirmation of the biblical text.

Is Hodge serious with this?

Besides, the ancient passages Hodge quotes above do not in fact sound like they’re describing dinosaurs. Flying serpents that flew in from the desert and bit people? Which dinosaurs flew? Sure, there was archaeopteryx, but these creatures looked like birds, not like serpents. Winged armies of snakes which produce deadly poisons? Also, the dragon Beowulf slew breathed fire—which dinosaurs did that, exactly? Finally, the monster Gilgamesh slew is also not described as a dragon (to the contrary).

You know what’s interesting? The only quotes Hodge lists that aren’t obviously not about dragons are the ones that use the word that is being translated “dragon” in English, but decline to describe the creature they reference. Huh.

I have training as both a historian and a classicist. I’ve taken classes on ancient historiography. One of the first things you learn when you read ancient historians is that they weren’t operating under the same conditions or methodologies as modern historians. Ancient histories are packed full of things that simply cannot have happened. They’re full of what are clearly gross exaggerations, along with supernatural events that almost certainly did not take place.

Here’s a good discussion of the works of Herodotus, who is considered the father of history:

Figuring out the fantastic

Occasionally the strive for authority and exactness falters and the reader is left wondering whether the narrator has been unreliable all along, such as when Herodotus’ observations truly defy credulity.

Take the gold-digging ants of India, “bigger than a fox, though not so big as a dog”; the winged snakes of Arabia that interfere with the frankincense harvest; the Arabian sheep with tails so long they need little wooden carts attached to their hindquarters, preventing the tails from dragging on the ground.

All these are instances in which Herodotean inquiry – despite his own claims to the contrary – slip beyond the realm of the authentic, credible and real.

But it would be a mistake to make too much of these examples. They are memorable only because they stand in such marked contrast to the accurate pictures Herodotus sketches elsewhere of the world.

And who can say for sure that the gold-digging ants, the long-tailed sheep and the flying snakes did not, in fact, exist? Some have argued that the gold-digging ants of India were actually marmots and Herodotus applied a Greek word for ant to a creature unknown to him but reminiscent (albeit faintly) of an ant.

Other creatures, however, take the reader fully into the realm of the fantastic. In his description of Libya, Herodotus says emphatically:

There are enormous snakes there, and also lions, elephants, bears, asps, donkeys with horns, dog-headed creatures, headless creatures with eyes in their chests (at least, this is what the Libyans say) wild men and wild women and a large number of other creatures whose existence is not merely the stuff of fables.

Some of these beings belong to a different, more archaic world, where the boundary between man and beast was fluid and uncertain. We can see a whole spectrum of more or less fantastic creatures, whose ranks included the Cyclops and Sirens of the Odyssey.

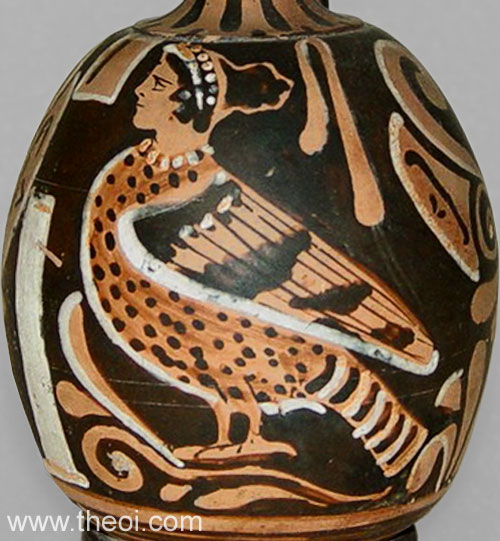

Ancient mythology around the world is filled with fantastical creatures. Consider Echidna and her young, for example:

Does Hodge mean to suggest that all of these creatures existed? Clearly not.

From where I’m standing, it looks like Hodge wants to look at ancient mythology and early attempts at history and take up anything that sounds like it even remotely could describe a dinosaur, while dismissing every other fantastical creature.

The image above should make one thing clear, though—the ancients were very good at mashing up different creatures to create something new and horrifying. We see this throughout the ancient world—sirens, anyone?

Dinosaurs do not need to have existed for someone to invent a creature that is part bird, part reptile, and in every way gigantic and horrifying. And the monsters of ancient story didn’t really look that much like dinosaurs—at all.

We’ve got this idea of what a dragon looked like in our heads, but what we think of as stereotypical dragon is actually largely a modern invention.

Here’s what we think of when we think dragon:

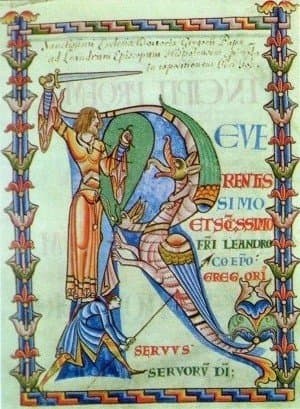

But while some medieval dragons resembled our modern archetype—perhaps because our image of a modern dragon was developed during this time—people in medieval Europe depicted dragons with a huge amount of variety:

In the above, you can see both the variety in dragon depictions and the act of mashing aspects of different creatures together, much like the Romans and Egyptians did centuries before. I’m reminded of that book my children found at the library once, where you can turn three sets of pages, combining different parts of animals to create creatures that are alternately hideous and ridiculous.

Ancient Chinese dragons also look more like mashups of existing creatures than they do like dinosaurs:

Is it possible that the ancients found dinosaur bones and invented creatures to fit them? Theoretically, and I have seen it suggested. Still, I doubt it, because what they drew doesn’t require ancient bones for an explanation. As I’ve noted, ancient and medieval “dragons” and monsters tended to be mixtures of existing creatures—creatures the ancients saw every day. Besides, it took a very long time for paleontologists to work out what dinosaurs actually looked like, even with the bones.

At most, any oversized bones the ancients may have discovered would have confirmed for them—in a general sense—that the gigantic and terrifying monsters of their mythology truly did exist.

Hodge finishes his piece as follows:

Satan wants people to accept the idea that dragons were myth because this assumption is another attack on the authority of God’s Word. Satan wants us to doubt God’s Word the same way he attacked Eve using a serpent in the Garden of Eden to doubt His Word (Genesis 3:1–6; 2 Corinthians 2:11). Were dragons a myth, or did they simply die out? It’s time to trust God’s Word over the fallible ideas of man, who was not there and not in a position of superseding God on the subject (Isaiah 2:22).

Of course dragons were real.

In light of the above discussion—and pictures—Hodges closing feels bizarre. Indeed, in light of the very quotes he includes in his piece, his closing descends into utter ridiculousness. Which dragons? Does he mean to suggest that there were flying serpents who flew in from the desert and bit people? Or winged armies of snakes? Or dragons that breathed fire? Does he suggest that the hydra, too, existed? What about sirens—or mermaids? How about unicorns, or basilisks, or griffins? There is no one universal ancient—or medieval—mythological creature. There were scads of them.

I have a Patreon! Please support my writing!