The Church as an Alternative Community, Part 1

Let me begin with a brief review. In my last few posts in this series I’ve been exploring the meaning of the Greek word ekklesia, which is ordinarily translated as “church.” This translation, however, is not necessarily the best because the English word “church” always has religious connotations, whereas ekklesia was a secular word that meant “assembly” or “gathering.” When it was used in the phrase “ekklesia of God” it referred to a Christian assembly, but the religious sense came from “of God,” not from ekklesia. Moreover, in the common Greek of the New Testament era, ekklesia denoted one particular kind of assembly, the gathering of citizens in a city to do civic business. In this sense, ekklesia had a meaning rather like that of the classic New England town meeting.

My last post focused on the implications of the broadest sense of ekklesia. If an ekklesia is an actual meeting of people, then a “church” exists when Christians gather together. The physical meeting of believers is essential to a right understanding of church. This stands as a critique, I suggested, of the American tendency to downplay the importance of church involvement. In our speech and practice, one can be a member of a church without showing up for the gatherings. This, however, is out of step with the basic notion of ekklesia.

With this review in mind, I want to ponder a bit further some implications of ekklesia for our understanding of the nature of a church.

A Church as an Alternative, Subversive Community

I want to begin to work on the implications of the more specific meaning of ekklesia: the gathering of citizens of a particular city. As we have seen previously, that is one of the meanings of ekklesia that would have been familiar to Christians in cities throughout the Roman Empire.

In light of this sense of ekklesia, consider the following thought experiment:

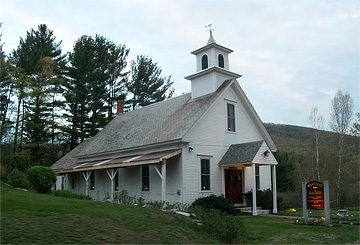

Suppose I were to move to New Hampshire in order to plant a new church there. I find a small town that has only one lifeless church and decide to set up shop there. This town, Athens by name, is governed, in typical New England fashion, by a town meeting that gathers periodically to oversee civic affairs. I begin my ministry with a Bible study in my home. After I have about twenty regulars, I decide to offer weekly worship services in the school gymnasium. I pass out flyers throughout the town. They proclaim: “Come to the Town Meeting of Athens in God.”

How do you think the locals would respond to the name of my church? It isn’t hard to imagine their confusion and likely ire. “Why are you calling yourself ‘the Town Meeting of Athens’ when we already have one?” they would ask. “What are you suggesting about our local government? Are you planning to replace our official town meeting? Are you a subversive? Or are you merely rude? We don’t need your kind around here!”

Of course we can’t know for sure that the citizens of Thessalonica reacted this way when they heard about the “ekklesia of the Thessalonians in God,” but it’s likely they were at least confused if not a bit miffed. Surely Paul and the other early Christian church planters knew what they were getting into by calling their gatherings ekklesiai (plural of ekklesia). No doubt they realized that referring to the Christian meetings as thiasoi (religious clubs) or synagogai (assemblies, synagogues) would be less troublesome. Yet they chose ekklesiai in spite of the potential for that name to cause trouble for the believers in a city that already had its own ekklesia.

It would seem that the early Christian use of ekklesia was indeed meant to be a bit subversive, but not in the ordinary manner. The first followers of Jesus were not intending to overthrow the established ekklesia of their cities. They were not plotting political rebellion. Yet, the Christians were setting up an alternative society which, as it grew, would indeed come to upset the apple cart of civic life throughout the Roman Empire. The Christian ekklesia was not some little religious club off in a corner or some innocuous gathering fit nicely into Greco-Roman society. Rather, it was a thumbnail sketch of the kingdom of God. It was a foretaste of the new creation yet to come. And, in this sense, it was an alternative community, even an unusually subversive one.

Tomorrow I’ll explain in more detail how this looked in the first century and how it might look in ours.