Do you know your true business?

Your response to this question will depend, I expect, on your circumstances. If, for example, you are a business owner, then you’d be able to answer easily by pointing to the enterprise to which so much of your life is devoted. If you’re not a business owner, you may be inclined to say that you don’t have a business, true or otherwise.

But, of course, there are a variety of meanings of the word “business,” in addition to “commercial enterprise.” When someone tells you, “That’s none of your business,” this isn’t a comment about your occupation. Rather, “business” in this context refers to something you care about or for which you have rightful responsibility.

I’ve been thinking about our business recently because I’ve been enjoying my annual reading of Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol. This classic story has much to do with business, and especially the question of our true business in life. Dickens doesn’t use the phrase “true business,” but he weighs in strongly on the matter, nevertheless.

As you no doubt recall, A Christmas Carol focuses on the character of Ebenezer Scrooge, who is introduced to us as “an excellent man of business.” The proof of this description is found in the fact that on the day of the funeral of his only friend and business partner, Jacob Marley, Scrooge managed to do a little business, coming up with “an undoubted bargain.” Whereas others might set aside time to remember a friend or grieve his loss, Scrooge focused on what matters most to him, advancing his commercial interests.

Scrooge’s understanding of his true business is underscored by an encounter he has with a couple of “portly gentlemen” who visit Scrooge while he is working. They ask him if he might help them “make some slight provision for the Poor and destitute, who suffer greatly at the present time.” Not surprisingly, Scrooge declines rudely. When one of the gentleman suggests that Scrooge might care about the plight of the poor, he responds, “It’s not my business . . . . It’s enough for a man to understand his own business, and not to interfere with other people’s. Mine occupies me constantly. Good afternoon, gentlemen!”

Scrooge understands his true business, or at least he thinks he does. His business is to advance his commercial interests, to add to his considerable wealth, and to focus all of his attention in such pursuits.

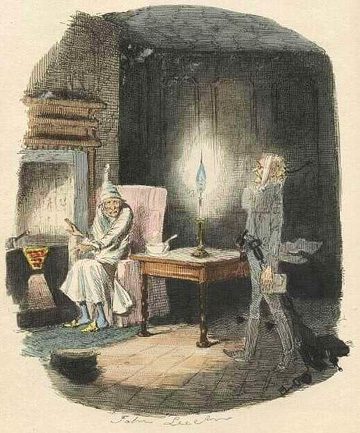

But then Scrooge has what we’d call a disruptive experience. It begins with a ghostly visit from his former partner, Jacob Marley. Marley’s ghost has been sentenced to a postmortem life of observing all the good he might have done in his mortal life but failed to do. Now, as a ghost, he has no capacity to help those in need and bears the sorrow of his uselessness.

When Marley explains his sad plight to Scrooge, Scrooge attempts to exonerate his former partner, “But you were always a good man of business, Jacob.” Marley’s response is striking, “Business! . . . Mankind was my business. The common welfare was my business; charity, mercy, forbearance, and benevolence, were, all, my business. The dealings of my trade were but a drop of water in the comprehensive ocean of my business!”

Yes, Marley had a business, the “trade” he shared with Scrooge. Yet that was not his real business. His true business as a human being was mankind, the common welfare, charity, mercy, forbearance, and benevolence. Yet, during his earthly life, Marley failed to attend to his true business. Scrooge, with Marley’s help, has the chance of making amends, of starting a new life. Of course, it takes the visits of three additional ghosts to transform the miserly heart of Scrooge.

When this transformation happens, Scrooge relishes his true business. He eagerly practices charity and benevolence. In fact, on the first day of his new life, Scrooge finds one of the portly gentlemen who had visited him earlier and pledges an extremely generous gift to help the poor. (Then, by the way, Scrooge goes to church, something that is rarely portrayed in the cinematic versions of A Christmas Carol. The 1999 version featuring Patrick Stewart does indeed include this scene, with Scrooge singing a “God Rest Ye Merry, Gentlemen.”)

Though Scrooge’s charitable giving is one clear sign that he understands his true business, we mustn’t overlook the fact that his true business also transforms his commercial business. We see this in the final stave of A Christmas Carol, when Scrooge promises to raise the salary of his clerk, Bob Cratchit. The narrator later explains that Scrooge was “as good a master” or, as we’d say, as good a boss “as the good old city knew.”

Thus, when we discover our true business, we don’t simply add on good deeds to our otherwise unchanged lives. Rather, everything we do is changed in light of our deeper and truer understanding of why we are on this earth. Even and especially what we do in our business becomes an expression of our deeper and wider business, the business of what Marley’s ghost calls the “common welfare,” or we might call the “common good.”

P.S. – If you are wondering how business as a commercial enterprise can be a genuine expression of our true business, let me recommend a couple of excellent books. Why Business Matters to God by Jeff Van Duzer lays out a compelling vision for the purpose of business beyond increasing shareholder value. The Economics of Neighborly Love by Tom Nelson offers a wider context for how to think about economics, work, and business in light of biblical truth and values.