We’re returning to our occasional series of posts on work and vocation (linked at the bottom of this post) in Christian history by Faith and Work Channel senior editor and Christian History magazine senior editor Chris Armstrong. Enjoy!

Usually, this was done in moderation and all was well. Occasionally, though, excess set in. This is what happened in the years just before Guinness was born, in the period historians call “The Gin Craze.” Parliament had forbidden the importation of liquor in 1689, so the people of Ireland and Britain began making their own, and drunkenness became widespread. Every sixth house in England was a “gin house.” An advertisement for one of these dens of squalor read, “Drunk for one penny, dead drunk for two pence, clean straw for nothing.” Poverty deepened; crime rose. And to help heal their tortured society, some turned to brewing beer. It was much lower in alcohol, the process of brewing and the alcohol that resulted killed the germs that made water dangerous, and it was nutritious in ways scientists are only now beginning to understand.

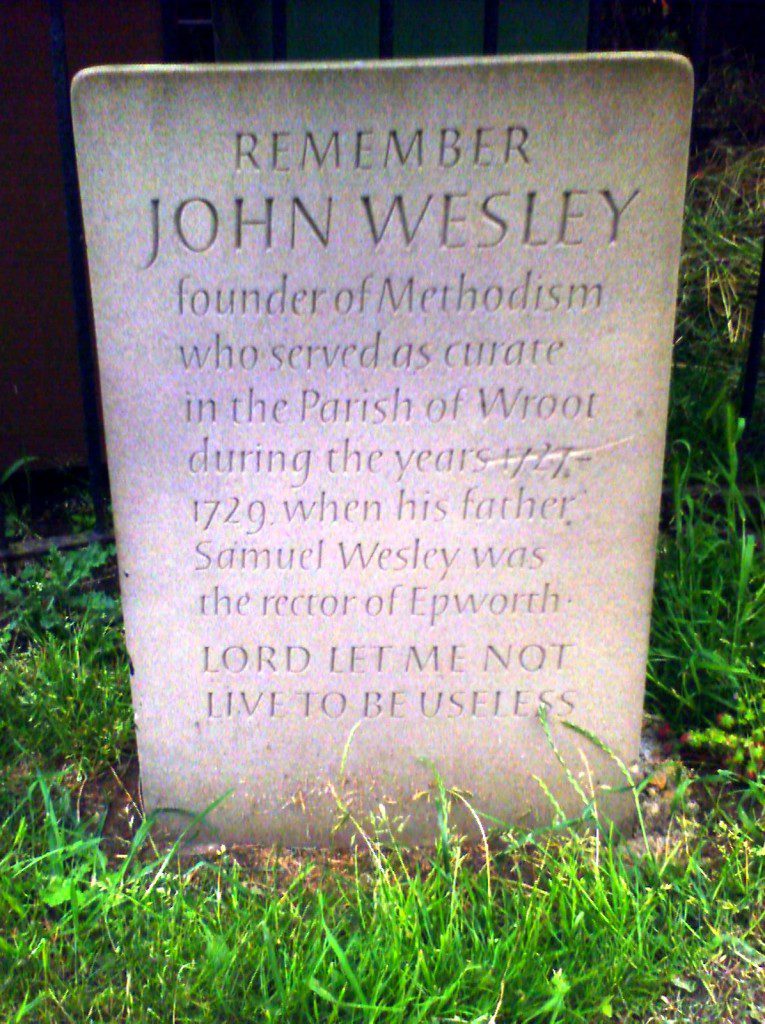

This young brewer, Arthur Guinness, fell under John Wesley’s influence. He heard Wesley teach “Earn all you can. Save all you can. Give all you can.” He understood from Wesley that the wealth he gained through business was evidence of a calling from God, and that it carried with it a responsibility to use his abundance for the good of humankind.

In 1759 Guinness had bought a little brewery. Within five years he acquired a great deal of public respect and profit. Influenced by a visit from Wesley himself, Guinness began a multitude of reforming and evangelizing efforts in Dublin even as he continued his work as a brewer – never perceiving a conflict of interest in the two endeavors. Just two examples: he founded the first Sunday school in Dublin and worked for an organization that tried to prevent dueling.

He also taught his own children the values he had learned from Wesley. Arthur’s children flourished in business and good works, and his grandsons Benjamin Lee and Arthur Lee gave generously to assist those made destitute by the potato blight that struck Ireland in the late 1840s. Arthur Lee (1797–1863) so aided his workers that they erected a monument of Connemara marble in his honor. Arthur’s grandson Edward Cecil engaged in far-reaching efforts to improve working-class conditions. After Guinness stock went public in 1886, he became the richest man in Ireland and used £250,000 to establish the Guinness Trust for “the creation of dwellings for the laboring poor” of Dublin and London.

Edward also encouraged the radical idealism of his company doctor, John Lumsden (1869–1944). With company approval, Lumsden tried to visit the home of every Guinness worker (nearly 3,000 people) as well as all the homes surrounding the brewery. He found nearly 35 percent of them inadequate, marked by stench, inadequate water supply, and alcoholism. In the wake of these discoveries, Guinness workers became the highest-paid per hour in Ireland. They were given access to company-provided educational and recreational opportunities: lectures, concerts, socials, exercise, cooking, and financial management classes. The company built playing fields, swimming pools, reading rooms, day-care centers, and parks, and allowed Lumsden to make his medical staff and equipment the best that money could buy.

That’s a small taste (so to speak) of the story of the godly Guinnesses. Now one more quick example—an American one. Across the Atlantic, Charles Welch (1852–1926), the former dentist who turned the “unfermented wine” invented by his father, Thomas, into the Welch’s Grape Juice empire, preferred to hire Methodists, as he thought this would create a wholesome environment at his Westfield, New York, factory. He built allegiance through annual picnics at the company camp on Chautauqua Lake, where employees gathered for, a newspaper noted, “baseball, motor boating, tennis, quoits, rowing, and swimming parties.”

Salesmen were invited to annual conventions featuring lectures, picnics, and prizes, as well as to services at the Westfield Methodist Episcopal Church, and to musical evenings. Welch was also generous to the town of Westfield and to worldwide Methodism, giving lavishly and signing all his checks “Charles E. Welch, Trustee.”

The Guinnesses, Welch, and many other godly businessmen saw themselves, in some sense, as trustees for the Lord. Their responses were heartfelt, their faith real, and their concern for improving the lives of their workers genuine. Certainly there were limits to their theology of work and economics. Many of their efforts, for example, come off today as patriarchal or patronizing rather than truly participatory–not drawing fully on the gifts and human agency of their workers. But their example can provide a positive challenge today for entrepreneurs and leaders in every field of economic work.

Originally published at Grateful to the Dead.

Previous posts in this series:

- Getting the beginning and end of the story right

- We were made to work

- Jesus the incarnate worker God’

- A brass-tacks, real-world theology of work and vocation

- Early Christianity and everyday work

- The contemplative contribution

- Luther on ordinary work and vocation

- Calvinists, Puritans, and the Wesleyan response

- How and why Methodists moved the market economy forward

Image: Wikimedia Commons.