“This book is about what lies behind such deceptively simple responses to problems we think we already understand or believe that we should act on even before we understand.” – Lila Abu-Lughod

After reading and facing criticism for our work and writing from men and women of all faiths, I try to find mentors and women to whom to look for encouragement as we waged this form of jihad on stupidity and ignorance.

I blog often and try to smash assumptions, but am often tired by incessantly proving I do not need “saving” in any aspect of my life.

Within the online community, I have been blessed to find colleagues and friends – including MMW and countless others – who think, challenge stereotypes, and critique in intelligent and mannered ways. (Truth be told, there is always the acceptable rage and rant that we also allow ourselves. Obviously.)

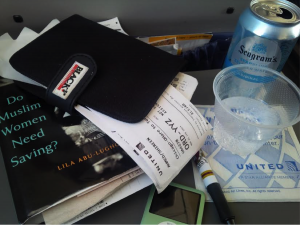

Last year, when I saw a wonderful tweet (thanks @kawrage!) and some beautiful rumours about Professor Lila Abu-Lughod’s upcoming book Do Muslim Women Need Saving?, my heart started to beat faster.

In a New York Times video interview, Abu-Lughod’s lovely, composed and smiling face describes the concept of her book. When she states that she knows and recognizes that there is no such monolith as “The Muslim Woman” it gave me butterflies in my stomach.

Many of my friends shared our excitement as our parcels arrived and we jumped into reading her work.

MMW has already published two reviews of this book: an overview of the topics covered by Tasnim and a more personal reflection by Eren; more recent reviews elsewhere include a piece by Dr.Naaz Rashid from LSE and another by Emily Villano at Feministing. My contribution to this series of reviews is more of an account of the emotional impact of being able to read and apply her work.

When I received my copy, I read it feverishly and quickly. I felt I had to stop myself at times and just exhale. I was drinking her powerful and measured words in too quickly. I let myself devour it and then I just sat back. My kids ate pizza for three days and the laundry went unwashed. (Not terribly uncommon, actually.)

It wasn’t simply an intellectual experience of reading a solid piece of work that criticized and called out the disingenuity of a “global industry” that felt the need to save women. It was also a very psycho-emotional experience.

Throughout the book, I found myself nodding vigorously as the author brilliantly poked and prodded at those heavy in their disdain and disregard for accepting Muslim women as individuals as opposed to being a one big sad and repressed group that needs to be spoken for and about.

When I read the book a second time for the purposes of writing about it, I used sticky-flags, highlighted and wrote in the margins so often I felt I might as well take a neon highlighter and just mark THE ENTIRE BOOK.

I had moments of intensity where I was clutching the book tightly because it resonated so deeply. Prof. Abu-Lughod was acknowledging her privilege by admitting her tenured position as a North American scholar, yet articulating so precisely what many Muslim women felt and what was reality. That humility and honesty was critical in being able to further relate to the author.

A friend of mine confessed that she sometimes slept with the book.

It might seem easy to laugh and dismiss these reactions, but this book has provided a source of comfort and relatability for many women. Far too often, I have felt exhausted when I see and read books and articles laced with Islamophobia and with Orientalist themes. I have ranted about letting Muslim women define their struggles and themselves. To read an entire academic book dedicated to this topic was a cathartic experience.

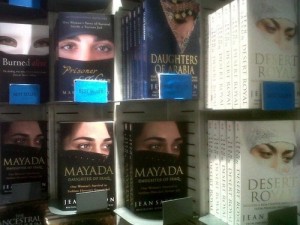

I almost felt giddy as I read Abu-Lughod’s flawless critiques of white-saviour mentality through historic missionary campaigns that showcased the difficulties of women in specific regions: “Some girls were criticized for making choices that went outside the rescuers’ scripts for them. In short, the story behind the news was complicated. It did not not fit the story of Muslim women oppressed by their culture.” (14)

Abu-Lughod’s challenges and gentle ridiculing of those who fetishize veiling were a breath of fresh air: “It seems that it is better to leave veils and vocations of saving others behind. Instead we should be training our sights on ways to make the world a more just place” (49).

One of the most important pieces for me when reading was how Abu-Lughod discusses the politicization of using Muslim women as an excuse to conduct military campaigns. Abu-Lughod has stated that the inspiration for this book came from when she questioned the US military invasion of Afghanistan, which called for freedom of the societally-imprisoned, burqa-clad women. When speaking of RAWA (a prominent women’s rights organization in Afghanistan) she writes: “[RAWA] did not see Afghan women’s salvation in military violence that only increased hardship and loss” (50). She continues to explain how the voices of actual Afghan women were not heard: “Unfortunately, only their messages about the excesses of the Taliban were heard, even though their criticisms of those in power in Afghanistan had included previous regimes.”

These salient points are seldom – if ever – presented in mainstream media; yet women’s rights were used to sell this invasion to an eager public, a public whose heartstrings were pulled and whose heads shook as they saw the depressing images of covered women in war zones.

Of the media, Abu-Lughod writes: “They presume that people, once they know, will not stand by, silent and apathetic” (58).

The reaction of the public can be to sign various petitions, financially support or watch different televised series and enable those whom Abu-Lughod defines as “Rescuers,” such as journalists-turned-saviours Nick Kristof and Sheryl Wudunn from ‘Half the Sky’ movement. These same Rescuers laud their own perseverance and power to save: “the overriding message of Half the Sky, like the other popular books discussed here, is that Westerners are the ones who must change the world” (63).

In the past, I have stressed the need for understanding the agency of Muslim women and their voices in telling what they need for support, instead of bossy, privileged strangers projecting *what* and *how* society feels they should receive. Lila Abu-Lughod persuasively argues that using a stereotypical theme of weak women in need of liberation from patriarchal and draconian societies is reductive. Problems that Muslim women face are not unlike those faced by women all over the world. They all have different contexts and different variables.

Abu-Lughod examines the folly of those who wish to politicize and unfairly manipulate the issues of Muslim women in order to further their own agendas:

“Clucking about ancient tribal honor codes will not get us to the heart of problems in Karachi or Bradford, or be met with sympathy even by women there. Asking women like Zaynab or ‘Aysha in Egypt, or my Palestinian aunt in Jordan, to renounce their faith, their identities as Muslims, or their deep sense of belonging to their families or communities shows a lack of respect” (226).

Prof. Abu-Lughod presents ideas that make us think: about how the world needs to help Muslim women gain access to support, opportunity and justice. And she also outlines the way in which to do so.

I recently wrote an open letter in response to a journalist who ignorantly used the metaphor of Muslim women and burqas as an example of those who are oppressed. I strongly suggested she read Do Muslim Women Need Saving? to educate and enlighten herself. I thought she could save herself from writing such pathetic articles in future.

I would strongly suggest this book for any person who identifies with any element of feminism.

I would strongly suggest this book to anyone who can read. Maybe to save themselves from overreaching and overstepping their attempts to be a saviour.

And save Muslim women from being saved.

In a way, Lila Abu-Lughod might have saved us all.