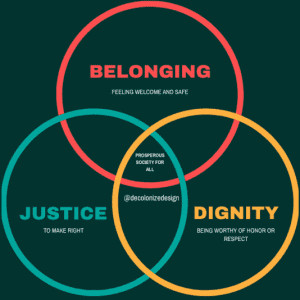

What is a progressive Christian? A progressive Christian confers dignity on all those who have been denied dignity. Actually, this is the mission of all Christians, not only the progressive ones. Actually, this is the mission of all citizens.

What is a progressive Christian? A progressive Christian confers dignity on all those who have been denied dignity. Actually, this is the mission of all Christians, not only the progressive ones. Actually, this is the mission of all citizens.

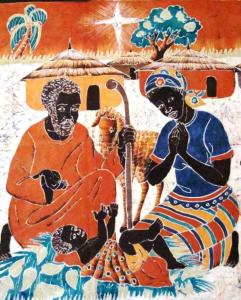

By giving attention to the blind, the lame, the lepers, and the tax collectors, Jesus conferred dignity on each one. Whereas these marginalized had experienced lack of respect if not humiliation, Jesus conferred God’s worth on each person. Christmas means that “He lowered himself to elevate us,” declares Joel J. Miller in a Patheos post.

Here is my contribution to this discussion: dignity is first conferred and then claimed. This practice of conferring human dignity began with God. God conferred human dignity by becoming human at Christmas. Now, the public theologian should aver, it’s our time to claim human dignity for ourselves and for those who have not yet experienced God’s final worth.

So at Christmas we celebrate the Great Dignity Conferral. God the creator and redeemer took human form in that Bethlehem baby. The incarnation is like a banner written by angels in the sky where God says, “You Are So Valuable that I Have Joined You.” According to St John Chrysostom, Christmas means that God “comingles” with us. “Because God is now on earth, and man in heaven; on every side all things commingle.” Within history, God has conferred dignity on human beings both individually and collectively.

From a Muslim source, I like this point of departure: “Human dignity is regarded as the recognition that human beings possess a special value intrinsic to their humanity, and as such are worthy of respect simply because they are human beings.” From this point of departure, where should we go? I recommend that the stated mission of the progressive Christian becomes this: let’s confer human dignity on every person who has not yet fully enjoyed being treated as one with dignity. (Painting by Lalit Jain)

Human Dignity in Philosophy and the US

We can thank the Enlightenment in Western culture for bringing the incipient notion of dignity [from dignitas or worthiness] to articulation. Western Europe had inherited a somewhat inchoate doctrine of dignity embedded within the biblical concept of the image of God, the imago Dei. Every human being, not just the royal family, has dignity.

As Western culture debated the embracing of democracy, the notion of universal human dignity came to the fore. Enlightenment sockdolager Immanuel Kant provided the description of dignity which has become the tacit if not the articulated essence of modern human personhood: each human person possesses dignity when we treat him, her, or they as an end, and never merely as a means to a further end. We can use things, but not persons. “Act in such a way that you always treat humanity, whether in your own person or in the person of any other, never simply as a means, but always at the same time as an end” (Kant 1948, 96). (Painting of Kant)

Kant’s formulation presupposes a moral relationship: one person treats another person as valuable. This relational factor obrains even though dignity appears to be individually claimed and owned. This relational formulation has stipulated and sustained our Enlightenment belief in the immanent and unalienable worth of the individual person.

We remember the 1776 U.S. Declaration of Independence for putting in words the eighteenth century commitment to dignity. Relying on a rationalist version of Christian natural law, the immanence of dignity became justified because it is self-evident. Modernity relies on “self-evident” endowments by our “Creator” which become “rights” to be guaranteed by governments.

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.

Even though the term dignity is not employed here, a phrase such as “endowed by their Creator” designates traits which are assumed to be inherent, innate, undeniable. The only warrant for writing such a declaration is the historical experience of the denial of dignity by England. There was a wrong to be righted. Subsequent American history records the ongoing process of dignity conferral to slaves, women, immigrants, and LGBTQ persons. Dignity must be conferred before it can be claimed. Once claimed, human dignity requires protection by legislated and enforced law. The allegedly self-evident quality of dignity provides moral and legal justification for revolutionary strategies to recognize dignity where it is not publicly recognized. 20th century philosopher Mortimer Adler ties human dignity, human personhood, and human rights together into an American package.

…man is a person, not a thing…,a distinction that is radically one of kind, not of degree: you can’t be more or less of a person or more or less of a thing. All the objects in the world divide absolutely into persons and things, and man, on earth at least, man and man alone is a person, that as such, that as such, he is created, created in God’s image and that, as a person with reason and free will, he had only as a person with reason and free will, does he have inalienable natural rights, especially those of citizenship and all the basic civil rights and liberties. And that, as a person, with reason and free will, he is innately imbued with the natural moral law, which is the guide of his conduct and the source of his obligations and which finally appoints to him a good or end or goal that transcends this temporal life and the welfare of the state as such. This is a body of notions that hang together, no one of which, I think, can be torn apart from the others.

Kant the Enlightenment philosopher is now dead and nearly forgotten. But, effective history (Wirkungsgeschichte) bears a commitment to dignity that is politically sacred to this present day.

Human Dignity in the United Nations

Following the genocides of the Second World War, the United Nations elected a Committee on Human Rights, headed by Eleanor Roosevelt, to articulate for the world the need for protecting human dignity. According to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights of the General Assembly of UN in 1948, “recognition of the inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world ….” Dignity provides the foundation upon which human rights are constructed.

Article 1: All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act toward one another in a spirit of brotherhood.

Although dignity is not precisely defined, the drafters of the UN Declaration took it for granted that everyone knows what it means and what it requires by way of political practice. Because the Western democracies and the Soviet Marxists could not agree regarding protection of individual rights, no definition of dignity was spelled out. The UN hoped it could rely on common acceptance and overlook any official ambiguity. What was not ambiguous was that the UN drafters presumed as self-evident that dignity is immanent.

Here is a tension in the very concept of dignity: is it conferred or immanent? “It [dignity] is not bestowed by persons or institutions, and does not derive meaning from any human action or status: it is a gift given and universally shared,” claims bioethicist Susan Hack. Yet, I contend that, phenomenologically speaking, dignity is first conferred or bestowed and then claimed. I add that God has already defined us as having dignity immanently as the first Christmas gift.

Dignitarian Politics

In his postmodern treatment of dignity, Gaymon Bennett at Arizona State University’s Center for the Study of Religion and Conflict says that “whatever else it may be, human dignity is that which is inherent and it is that which can be, and must be, recognized….Moreover,…it is the source of political goods. The recognition of dignity issues in freedom, justice, and peace, and its violation brings with it outrage and disunity” (Bennett, Technicians of Human Dignity: Bodies, Souls, and the Making of Intrinsic Worth 2016, 142).

Even though dignity presupposes an ontology, its decisive value is practical. Bennett avers that conceptualizing dignity in terms of intrinsic value is a recent development, a resistance against growing biopower. “Dignitarian politics are an integral part of our collective ethical imaginary,” he contends. “Dignitarian politics…are valuable because they serve as ethical equipment and not primarily because they offer a grounding truth for ethical theory” (Bennett, The Politics of Intrinsic Worth 2019, 242). In the practical fight for human equality in the face of existing stratifications and marginalizations, dignity is the most effective weapon.

What the UN needed was an ontological or metaphysical grounding of human dignity without appeal to one or another religious tradition. Regardless of the ontology, what the UN earnestly wanted was the practice of protecting and conferring human dignity. (Photo: Gaymon Bennett)

Here is the ethical or practical value of dignity: the presupposed immanentist ontology provides justification for moral judgment and for restorative if not constructive legal action. Dignity is assumed without argument to be archonic. Dignity is built-in, innate, and universal. By making such an assumption, UN framers could avoid religious preference. “The key framers of the document affirmed an inherent human dignity in order to provide an explanatory basis for the validity of universal human rights while eschewing any religious or metaphysical justification for this affirmation” (Hughes 2011, 1).

Should the public theologian hide or expose a theoretical tension that remains buried here? On the one hand, many persons and peoples in our world today do not experience or exhibit dignity, yet we can affirm theologically that they have dignity despite their apparent lack of dignity. On the other hand, non-religious entities such as the UN rely upon such a universal claim despite the fact that such a universal claim must itself rely upon a transcendent grounding. In short, without a theological grounding, the very concept of human dignity floats like a cumulus cloud in an updraft.

Both progressive and conservative Roman Catholic thinkers claim to know where that dignity is grounded, namely, it is grounded in the imago Dei.

Human Dignity as the Vatican’s Pastoral Ministry to the World

From the Second Vatican Council (1962-1965) to the present, the Roman Catholic Church has come to see itself as the world’s shepherd, guiding the world’s peoples toward a realization of their inherent dignity. Saint John XXIII “demands the acceptance of one fundamental principle: that each individual man is truly a person. His is a nature, that is, endowed with intelligence and free will. As such he has rights and duties, which together flow as a direct consequence from his nature. These rights and duties are universal and inviolable, and therefore altogether inalienable.” St. John XXIII, Paccem in terries (1963) §9;

For the church, this dignity is, first of all, immanent because it is written in the natural law readable by every rational soul. This mandate to recognize human dignity is articulated in Gaudium et Spes §16. “In the depths of his conscience, man detects a law which he does not impose upon himself, but which holds him to obedience…. For man has in his heart a law written by God; to obey it is the very dignity of man; according to it he will be judged.” One implication: prevent abortion and prevent human embryonic stem cell research, both of which destroy an embodied soul. The Vatican champions the protection of the embryo on behalf of human dignity within the sphere of dignitarian politics.

God’s law is written on the heart of natural humankind, according to Roman Catholic natural law theorists. So also is dignity. This has become the tacit political theology of the Roman Catholic Church in our generation. “At the Second Vatican Council in the 1960s,” writes Bennett, “dignity was put forward as an answer to the problem of how the church should relate pastorally to the secular world….it also raised the question of whether human dignity, framed as intrinsic and universal, could be recognized and understood apart from the church’s theological vernacular and doctrinal commitments” (Bennett, Technicians of Human Dignity: Bodies, Souls, and the Making of Intrinsic Worth 2016, 4).

The church sought “to figure dignity in such a way that it could be discursively taken for granted” (Bennett, Technicians of Human Dignity: Bodies, Souls, and the Making of Intrinsic Worth 2016, 8). The post-Vatican II church rode the UN horse. “Humanity, in its essence and need for actualization, is a common object of responsibility for the church and the United Nations” (Bennett, Technicians of Human Dignity: Bodies, Souls, and the Making of Intrinsic Worth 2016, p.30).

Is Dignity Archonic or Eschatological?

Just to clarify the vocabulary, archonic (the Greek term, arche, means both origin and governance). Any archonic justification grounds essence in origin.

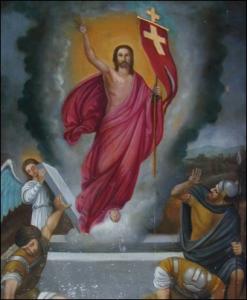

Roman Catholic natural law theory grounds immanent dignity in our origin. Our origin includes the imago Dei given by God to Adam and Eve. An epigenetic or even eschatological ontology would instead ground human dignity not in the past but rather in the future. If the Easter Jesus Christ–not the past Adam and Eve–constitute the fulfilled imago Dei, then today we look forward to our own shared resurrection in the eschatological fulfillment. We proleptically anticipate our oneness with the true imago Dei, the eikon tou theou, the risen and returning Christ. Does the Vatican consider this? Yes.

This appeal to natural law in the created order presumes as self-evident that dignity is immanent, inherent, innate, archonic. Yet, dignity is also eschatological.

- 39. For after we have obeyed the Lord, and in His Spirit nurtured on earth the values of human dignity, brotherhood and freedom, and indeed all the good fruits of our nature and enterprise, we will find them again, but freed of stain, burnished and transfigured, when Christ hands over to the Father: ‘a kingdom eternal and universal, a kingdom of truth and life, of holiness and grace, of justice, love and peace.’ On this earth that Kingdom is already present in mystery. When the Lord returns it will be brought into full flower. (Gaudium et Spes)

Now, which is it: immanent or imminent? Is dignity archonic? Or, is it conferred by God eschatologically? Or, might it be a synthesis? “They are synthetic in that destiny and origin are folded into each other; the one indicates and is constituted by the other. Their relation is nonlinear in that destiny is not a state subsequent to origins but rather is the actualization and completion of the rule anticipated and prescribed in the origin” (Bennett, Technicians of Human Dignity: Bodies, Souls, and the Making of Intrinsic Worth 2016, 71).

Or, to say it my way, the eschatological kingdom will retroactively determine what has been archonic all along. Dignity is first imminent, then immanent. When we confer dignity where it is denied today, we are proleptically affirming what will be eschatologically true. To confer dignity on a person who is denied dignity is to act out of faith, to act implicitly out of trust in God’s future. (Resurrection fresco, Franciscan church, Chania, Crete)

Conclusion

At Christmas we celebrate God’s Great Dignity Conferral. God conferred human dignity upon each of us. Now, it’s time for us to claim it for ourselves and to spread the conferring to all those who have not yet claimed their final dignity.

I need to hear” the Christmas story again, says Nadia. I need to hear “about how God enters fully into the muck of our existence and brings new life.”

I want progressive Christians—actually, everybody–to protect human dignity. More precisely, I want all persons of good will to confer human dignity when it is not recognized. I believe it is the mission of all Christians and all citizens of the modern world to confer human dignity whenever and wherever it is unrecognized, denied, or violated. I believe that conferring human dignity is the heart of liberation theology. Conferring human dignity is the heart of nonviolence. Conferring human dignity is the heart of public theology.

As suggested above, the impetus to protect dignity and confer dignity exhibits a theoretical tension. To protect dignity assumes that dignity is already present, that it is threatened and that it needs protection. To confer dignity, in contrast, implies that it is absent. Phenomenologically speaking, our conferral actually constructs a dignity which was missing. Is inherent dignity, then, a social construction? The theoretical tension between these two is exposed in the question: is dignity immanent or is dignity constructed?

The tension can be resolved by trusting in God. What does this mean? First, to trust God is to have faith in what is unseen. If human dignity is not seen, we must place our trust in God that dignity is present, valid, and real. Second, ontologically, it is God’s eschatological future which determines retroactively what is real in the present. Dignity for each of God’s beloved creatures is eschatologically real. Our task today is to believe it, trust it, and to confer dignity upon those without dignity. For us to confer dignity today is to act proleptically by borrowing dignity’s immanent reality from God’s imminent future.

▓

Ted Peters is a Lutheran pastor and emeritus seminary professor. His one volume systematic theology is now in its 3rd edition, God—The World’s Future (Fortress 2015). He has undertaken a thorough examination of the sin-and-grace dialectic in two works, Sin: Radical Evil in Soul and Society (Eerdmans 1994) and Sin Boldly! (Fortress 2015). Watch for his forthcoming, The Voice of Public Christian Theology (ATF 2022). See his website: TedsTimelyTake.com.

▓