Sin and Grace

ST 2156. Sin 6. Sin and Grace

Sin and grace. If nobody cares about sin, will grace go unnoticed?

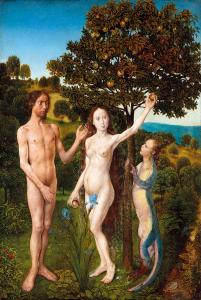

This is not a problem for Patheos columnist Keith Giles. He contends that we are obsessed with sin. How I wish this were true. If it were true, then we could drum up some interest both in understanding sin as well as repenting from sin. We could also drum up greater appreciation for God’s grace. (Artist: Lucas Cranach, 1526)

Giles diverts our attention when he focuses solely on the “sin-obsessed version of Modern Christianity.” Sin-obsessed? Really? This does not describe the people I know. It does not describe either the general populace or my congregation. On the one hand, most people in our wider society are so averse to sin that they tell lies on top of lies just to avoid the subject. On the other hand, those within my congregation are so grateful to God’s grace that they’re conscientiously looking for ways to love their neighbor. Perhaps Keith Giles and I run in different circles.

Getting to the bottom of sin is not easy. Describing sin as a cluster of moral imperfections–as Daniel Fincke does–is like a floating a fisher’s bobber on top of the lake surface. It treats the deep as if it were shallow. Rebecca Florence Miller dips a bit deeper by introducing combos such as individual sin combined with communal sin as well as the interaction of sin with repentance. “Christians ought to repent of both communal and individual sin.” Logan Patriquin dips somewhat deeper by explicating “Wesley’s understanding of universal human sinfulness and regenerating grace.” Grayson Gilbert dips still deeper by recognizing that “Sin is not just a work that is manifest in our actions, it is a position of our being.” And further, Gilbert points out that “people go to great lengths to hide sin,” We’re getting closer to the bottom.

In my role as a systematic theologian, I’ve been sonar sounding sin’s depths for some decades now. Yes, there’s a level of intractable mystery connected with sin. Yet, it is worth a sustained pursuit to understand sin and grace theologically. This post is the sixth in the series: (1) Sin 1: Sin? Really? (2) Sin 2: Sin as Self-Justification; (3) Sin 3: the Visible Scapegoat: (4) Sin 4: the Invisible Scapegoat; (5) Sin 5: Sin Boldly! and now (6) Sin 6: Sin and Grace. Holy daily living includes the imperative: sin boldly!

The Lie Prevents Sin-Obsession

People in our wider society are not obsessed with their own sin. The sin of others? You betcha. (Art: The Scapegoat by Holman Hunt)

If we bury sin deeply under a pile of lies, we cease even to be aware of our own sin let alone become obsessed with it. As I observe human behavior in general, I see the following.

First, we draw a line between good and evil.

Second, we place ourselves on the good side.

Third, on the evil side we place sinners, evil-doers, nincompoops, and ignoramuses.

Fourth, we tell ourselves a lie. We conceal from ourselves what we have just done.

We then feel justified at marching for righteousness. Further, we are ready to perpetrate violence against those we’ve place on the evil side our the line we drew.

Those on the evil side of the line I call “visible scapegoats.” The lie I call “self-justification.” In the Garden of Eden (Genesis 2-4), Adam and Eve justified themselves by scapegoating God. If you want to know what sin is, try reading the Adam and Eve story again.

Whom do we select for the evil side of our line? Our boss? The president? Those who support abortion? Those who oppose abortion? Those undesirables encroaching on our neighborhood? The Russians? God? Or those who believe in God? As long as we have one or more scapegoats, the only sin we become obsessed with is somebody else’s‘.

The New Atheists draw a line between good and evil

The new atheists are obsessed with the sins of religious people. They draw a line between good and evil and they place religion on the evil side. After all, religion is responsible for human violence! This is the atheist liturgical refrain: get rid of religion and get world peace.

Because religion is dogmatic, the evangelical atheists contend, religion is intolerant. And the intolerance of religion is responsible for human evil. According to Sam Harris, “”Some propositions are so dangerous that it may even be ethical to kill people for believing them. This may seem an extraordinary claim, but it merely enunciates an ordinary fact about the world in which we live. Certain beliefs place their adherents beyond the reach of every peaceful means of persuasion, while inspiring them to commit acts of extraordinary violence against others.” If you are religious, then others had better protect themselves from you.

Harris recommends the non-Muslim world consider a possible preemptive nuclear strike against Muslims. “The only thing likely to ensure our survival may be a nuclear first strike of our own” (Sam Harris, The End of Faith, 131). In short, the way for an atheist to prevent religious violence is to obliterate the religion before it can strike. Because religion is evil, we are justified in prosecuting war against religion. That’s the logic.

This illustrates a key feature of sin when the depths are grasped, namely, self-justification justifies preemptive violence against the scapegoat. In the new atheist worldview, we can scapegoat religion and justify eliminating religion.

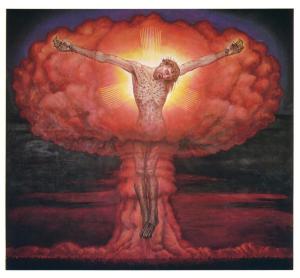

“Religion causes wars by generating certainty,” says Richard Dawkins, the Pied Piper of the new atheism. Virtuous atheists do not promote violence. (So they say). Rather, virtuous atheists on the good side of the line advocate good things such as ecological ethics, respect for science, racial justice, and gender justice along with world peace. Allegedly, the evil religious believer rejects everything the atheist supports. This provides the atheist with justification for scapegoating religion. (Art: “Nuclear Crucifixion,” Alex Grey 1960)

No sin-obsession here. At least on the atheist side of the line.

Paradoxically, the new atheists contend that it is religious people who self-justify by scapegoating. Richard Dawkins, ties us up in knots. He confounds us. How? By ascribing the Christian understanding of sin to people of faith rather than to himself and his minions. “And religious faith really does motivate people to do terrible things. If you really, really believe that your god wants you to be a martyr and to blow people up, then you will do it. And you will think you’re doing it for righteous reasons. You will think you are a good person.”

This does not mean that Dawkins is wrong in his description of religion. Rather, it’s a question of logs in eyes.

Do not judge, so that you may not be judged. 2For with the judgement you make you will be judged, and the measure you give will be the measure you get. 3Why do you see the speck in your neighbour’s eye, but do not notice the log in your own eye? 4Or how can you say to your neighbour, “Let me take the speck out of your eye”, while the log is in your own eye? 5You hypocrite, first take the log out of your own eye, and then you will see clearly to take the speck out of your neighbour’s eye. (Matthew 7:1-5)

Just as Satan casts out Satan, sin casts out sin

It is as amazing as it is intractable that this subtle understanding of sin has become the very weapon to fight against somebody else’s sin. Pointing out another’s speck rather than one’s own log leads to a long descending spiral downward toward the abyss.

Atheist scapegoating of religion cannot help but lead to violence. Here’s a case in point. In 2015 in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, lone wolf Craig Stephen Hicks murdered three Muslims. His Facebook page made clear he had been inspired by new atheist books written by Richard Dawkins, Sam Harris, and others. By obliterating the lives of three Muslims, Hicks is protecting all of us from religious violence.

Should we defend religion? “There is no denying that religion has historically been used to justify violence,” admits Lutheran theologian William Rodriguez. Yes, of course, Dr. Rodriguez. And religious people should repent. Yes, of course.

But, rather than defend religion against its critics, I wish to address a different topic: what is sin? Because both religious and anti-religious people sin, we still need to grasp sin when it applies to ourselves. What makes all this a knot difficult to untie is that sin’s mechanism is buried beneath a pile of lies that take the form of self-justification and scapegoating.

How can we untie this atheist knot?

Illustrious theologians and scholars have provided astute refutations of the new atheist excesses. I can only admire Alister McGrath, William T. Cavanaugh, John Haught, Wolfgang Palaver, and Ted Davis. My own modest contribution to the discussion is “Evangelical Atheism Today: A Response to Richard Dawkins.”

But defending religion against atheist attacks will not help untie Dawkins’ knot regarding sin. Dan Vander Lugt almost unravels the knot. “Hearts unaware of their own wickedness corrupt faith of any kind into evil and violence.”

In an attempt to untie Dawkins’ knot by research, empirical evidence turns our gaze toward human nature rather than religion. Joshua David Wright and Yuelee Khoo put in observational terms what theologians have commonly called, original sin.

The ‘religion as cause’ argument implies that religious faiths are more inherently prone to violence than ideologies that are secular. Following an evaluation of the scientific literature on religion and violence, we argue that wherever evidence links specific aspects of religion with aggression and violence, these aspects are not unique to religion. Rather, these aspects are religious variants of more general psychological processes.

Unfortunately, we cannot combat self-justification accompanied by scapegoating with fact, evidence, or appeal to fairness. This is because the lie is so powerful. Only the call to repentance combined with the news of God’s grace can accomplish this.

In sum, the sin-obsession of the new atheists is the alleged sin of religious people. Not their own. Sin is one of those theological concepts that may resist objective or scholarly explanation. Why? Because sin is existential. Each of us must penetrate our own lies that cover up self-justification and scapegoating. When we are satisfied with living the life of the lie, then we’re not likely to be sin-obsessed.

The Law-Gospel Dialectic within the Sin and Grace Dialectic

How can we penetrate the lies which hide our inner self from the truth about ourselves? The Lutherans have an answer. It’s called preaching the Law-Gospel Dialectic. First, we condemn with the Law. Then, we forgive with the gospel. The Law-Gospel Dialectic is the chief form taken by the Sin and Grace Dialectic for Lutherans. Is the Law-Gospel Dialectic effective in today’s preaching during worship?. (Art: “Law and Gospel” by Lucas Cranach the Elder, 1529)

I’m a Lutheran. When the Lutheran preaches, the task is clear: convict of sin and liberate with forgiveness. The law of God reveals to us our sinful state and our abject helplessness before the throne of grace. After hearing the law, we are supposed to feel as useless and worthless as horse pucky. Then, when we feel guilty, shamed, and worthless, the gospel comes to the rescue. The gospel pronounces the good news of divine grace alone (sola gratia), namely, we are forgiven of our sins and justified by our faith. After hearing the gospel, we are supposed to feel as joyful as Revelation’s angels singing te deums. In principle, I affirm that this is excellent theology.

In practice, however, the law-gospel dialectic fails to deliver. Why? Because of who the people are in the pew that are listening. Who are they? Let me divide the pairs of ears listening to me preach into two groups: (1) those who rejoice in God’s law and (2) those who feel ontologically worthless.

Rejoicing in God’s law

The first and larger group in the congregation who listen to my proclamation of God’s law rejoice. The Psalmist, after all, did not fear condemnation by God’s law. “Happy are those [who] delight in the law of the Lord” (Psalm 1:2).

Those sitting the pews don’t feel obsessed with their own sin. No. Rather, they love God’s law because it reminds them of what they already want to do, namely, love God and love neighbor. God’s law doesn’t make my Christians in the pew feel guilty. Rather, it makes them feel inspired, motivated, enthusiastic. They already like God. They like God’s law. So, they’re not sin-obsessed because they have already embraced the gospel. They have already been graced by God. They know it. And they love it.

What is the greatest sin?

Giles asks: what is the greatest sin? Here is his thoughtful answer. “I’ve always believed that the greatest sin anyone could commit was related to the Greatest Commandment. I mean, if it’s the Greatest Commandment, then to break it would seem to be the greatest sin. So, what’s the Greatest Commandment?” What’s that commandment again?

““Teacher, which is the greatest commandment in the Law?” Jesus replied: “‘Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind.’ This is the first and greatest commandment. And the second is like it: ‘Love your neighbor as yourself.’ All the Law and the Prophets hang on these two commandments.” (Matt. 22:36-40) (Art: “Come Unto Me” by Wayne Pascal)

Let’s run this through the Law-Gospel filter. If the Law-Gospel dialectic does its prescribed work, then we would expect the following. The listener would hear God’s law of double love and feel judged at missing the mark. Of falling short. Of loving less than the law requires. The judged person would feel like horse pucky. Her or she or they would then confess, repent, and resolve to love more fully.

The gospel would then be presented. The gospel would present God’s gracious forgiveness. The gospel would declare that we are justified by God’s grace through faith. Once justified, grace would also offer the power of the Holy Spirit to enable self-sacrificial loving. The dialectic of law and gospel would then arrive at spiritual fulfillment.

Is this what the souls in my congregation ask for in my homilies? No. All that stuff about sin and forgiveness is now behind them. They want to get on with the loving part. Shouldn’t the pastor simply applaud? How might the dialectic of sin and grace help us here?

Feeling Worthless? The Homeless

Now, the matter gets still more complicated. In my parish ministry, I have frequent contact with homeless persons. Sometimes they come to worship with all their possessions in a backpack and shoulder bag. In addition to the threats of low temperatures, rain, and unreliable food access, they can be caught in the downward spiral of discouragement, depression, and self-destruction. Here’s a quote of a voice coming from inside a tent in a homeless encampment: “I hate myself. I just wanna be dead.”

Now, the matter gets still more complicated. In my parish ministry, I have frequent contact with homeless persons. Sometimes they come to worship with all their possessions in a backpack and shoulder bag. In addition to the threats of low temperatures, rain, and unreliable food access, they can be caught in the downward spiral of discouragement, depression, and self-destruction. Here’s a quote of a voice coming from inside a tent in a homeless encampment: “I hate myself. I just wanna be dead.”

I recently gave some cash to two such men. Later they reported they had distributed much of this money to other homeless people who badly needed food. Get this: while feeling worthless and experiencing depression, they obeyed Jesus’ double commandment to love.

Of what value would the Law-Gospel dialectic be in this situation? The law of God already serves as a rescue, as an inspiration.

Public Theologian Robert Benne is right when he reminds us that the divine law in itself is not salvific.

The action of the law in the world is nonredemptive. We are not saved by the energies of the law, no matter how positive they might be. Robert Benne. Paradoxical Vision (Kindle Locations 910-911).

Even so, the divine law can very well be inspiring to many of us whose hearts are turned toward God.

Before the transition to the conclusion, let me add a brief postscript. On a recent Sunday morning shortly before worship. one of the homeless men walked into church and sat down in his usual place, a third row pew. The previous night had been cold and rainy. I walked up to share a greeting. With a giant smile he said, “It’s just so great to be alive! Don’t you agree, Pastor?” Go figure.

The Sin and Grace dialectic leads to: sin boldly!

No, sin-obsession is not descriptive of either the human race or life in the congregations I serve as pastor. Is sin important! Absolutely. I applaud those Patheos theologians who mull it over and attempt to provide understanding, illumination, and inspiration. By engaging in discourse clarification, the systematic theologian becomes a public theologian that brings exposure to the lies we tell ourselves.

Why might sin-obsession be less prevalent than assumed? I have suggested two reasons. First, the very phenomenon of human sinning includes the lie. The lie takes the form of self-justification and scapegoating. When we are sinning, we hide this from ourselves. When we are successful at hiding the truth from ourselves, we cease to be sin-obsessed. At least with our own sin. We’re quick to point out the sins of others, to be sure.

Second, many Christians simply swim in God’s grace without testing the temperature of the water. They love God’s law, especially when God’s law inspires us to love both God and neighbor. This does not eliminate sinning, to be sure. But it does keep our focus on what’s most important.

The sin and grace dialectic is the most precious gift from our redeeming God to the human race. In the form of the Law-Gospel dialectic, God’s grace offers forgiveness, comfort, joy, and an inner willingness to pursue love of God and love of neighbor.

Yet, we do not experience it as a Sunday morning two-step. When listening to the pastor preach, we do not begin with a condemnatory law that leads through feeling like horse pucky to forgiveness and then renewal. Rather, the entire sin and grace dialectic seems to be present in all steps at every moment. When sin and grace comes to awareness in the Christian’s mind, the focus turns to: how might I exercise the love of neighbor that God’ commands? In sum, the gospel has genuinely inspired some devout persons among us.

I’m just thankful that God’s grace is at work, regardless of how it works.

▓

Ted Peters is a Lutheran pastor and emeritus seminary professor. His one volume systematic theology is now in its 3rd edition, God—The World’s Future (Fortress 2015). He has undertaken a thorough examination of the sin-and-grace dialectic in two works, Sin: Radical Evil in Soul and Society (Eerdmans 1994) and Sin Boldly! (Fortress 2015). Watch for his forthcoming, The Voice of Public Christian Theology (ATF 2022). See his website: TedsTimelyTake.com.

Ted Peters is a Lutheran pastor and emeritus seminary professor. His one volume systematic theology is now in its 3rd edition, God—The World’s Future (Fortress 2015). He has undertaken a thorough examination of the sin-and-grace dialectic in two works, Sin: Radical Evil in Soul and Society (Eerdmans 1994) and Sin Boldly! (Fortress 2015). Watch for his forthcoming, The Voice of Public Christian Theology (ATF 2022). See his website: TedsTimelyTake.com.

▓