St 4111. Afterlife 1

Denial of Death

I don’t want to die. Might denial of death make me feel better?

When I think about dying and departing this world, I imagine missing out on what’s happening. I’ll miss out on what my grown kids are talking about. On how my precious grandchildren are growing up. On the next new technological marvel from Apple. On the next losing season for the Oakland A’s. It bothers me to think the world will go on without me as a part of it.

Like so many other children, at age four or five I was frightened of the dark. I feared falling asleep, worrying that I might never wake up.

A recurring dream haunted me. In this dream, I would crawl out of my bed and look underneath. There I would see a wooden box filled with dried human bones. Were those my bones?

Oh, yes, my mother comforted me. She stressed that on the other side of death Jesus would be waiting for me in the resurrection. So, in the years since I’ve lived with a double mind. The combination of haunting fear and comforting grace.

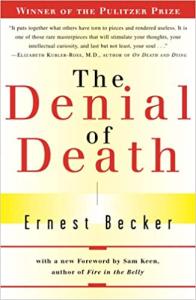

The Denial of Death by Ernest Becker

“Death is the great wrecking ball that destroys everything,” writes Christian social thinker Dinesh D’Souza (D’Souza 2009, 3). Might it help to just pretend there is no death and hope it goes away?

Jewish social thinker Ernest Becker constructed a theory of civilization based on our denial of death. Our anxiety over awareness of our impending death is something we just can’t live with, he observed. So, we deny it.

“The basic motivation for human behavior is our biological need to control our basic anxiety, to deny the terror of death,” wrote Becker in 1973 (Becker 1973). The denial of death is the foundation on which civilization is built.

How do we protect ourselves from the threat of death? By looking both ways before crossing the street, to be sure. By going regularly to the doctor. By keeping to a healthy diet with accompanying exercise.

There are other more disguised ways for us to deny our death. We try to steal the power of life from others. Ritually, archaic cannibals would kill their strong enemies and drink their blood, imbibing their life-force. Non-ritually, we today go to war and steal the victims’ bank accounts or diamond mines or petroleum reserves. By pretending that we are strong while others are weak, we can repress our fear of death. This is a delusion, of course. But we shed blood in wars around the world to sustain this delusion.

The delusional smokescreen that hides our own denial of death may include expanding our circle of social media friends, driving the biggest truck, graduating from the best university, hiring the best wealth management firm, exerting power over others in sports, business, or government. We might even immortalize ourselves with big donations to institutions which will engrave our name on a sidewalk brick. [Pssst. I’ve actually done this.]

Denial of Death Enkindles the Fires of Sin

Becker’s theory—the denial of death—shines light on what we ordinarily keep in the darkness. It’s anxiety lurking within our darkness. Anxiety here refers to our fear of non-being, our fear of dropping from existence into non-existence. Anxiety is a perpetual existential threat.

This fundamental anxiety lies below consciousness. Yet, like a volcano, anxiety is ever ready to erupt into violence. Our violence has a purpose, namely, to steal the life force of someone else. To think we can prevent our own death by stealing life from others is a delusion, of course, as we just noted. But it’s a powerful delusion. This delusion drives history.

This theory—the denial of death—places the Jewish Ernst Becker at the same barbecue with Christian theologians Reinhold Niebuhr and Paul Tillich. All three grasp the same insight: anxiety provides the garden within which human sin grows. When I wrote my first book on sin, Sin-Radical Evil in Soul and Society(Peters 1993), I started where these three thinkers had left off.

The Afterlife? What do our religions teach?

Death and the possibility of an afterlife generate religious hopes like soccer’s World Cup generates fan excitement.

Does religion support the denial of death? Some critics, such as Christel Manning, reduce religion to only the denial of death.

“Religion also answers questions about what happens after death, whether through complex and varied conceptions of reincarnation in Buddhism and Hinduism, or through comforting beliefs that we will see loved ones again in heaven, as in some Christian traditions.”

Whether “denial of death” is the right term or not, it is certainly the case that death and afterlife are cooking on religion’s front burner.

What are the afterlife possibilities? Let me list some eschatological possibilities that have appeared in human history over the last five thousand years or so.

- The Denial of Death

- Naturalism: When yer dead yer dead!

- Astral Body? Ka? Or Angel?

- Third Day Afterlife

- Immortal Soul

- Reincarnation

- Near Death Experiences

- Communication with the Dead

- Absorption into the Mystical Infinite

- Resurrection of the Body

- Heaven

- Hell

- Purgatory

- Universalism, Grace, and Hellfire

- Predestination & Destination

My plan in this series of posts on “Afterlife” is to look at a number of religious and philosophical possibilities. Could any of them be true? Could any of them provide comfort in the face of existential anxiety? Get ready to click.

Faith as the Antidote to Denial of Death

The single most effective antidote to denial of death is faith. I mean faith as trust. If you trust, you don’t sin. The people around you will like you better if they feel unthreatened. People around you will feel comfortable when they become confient that you will not attempt to steal their life force. Your disposition of trust will elicit others’ trust in you.

Writing in The Christian Century, Samuel Wells parses faith into two: belief and trust. He says he prefers trust.

“There are two kinds of faith, belief and trust. And here’s the irony: God’s faith in us is belief. It’s irrational, far-fetched, and mysterious. There’s no good reason for it, but everything depends on it. Our faith in God is trust. It’s saying, ‘There are going to be setbacks, misunderstandings, and patient rebuilding. But I only want to be with you’.”

Death is a setback. But the Christian gospel tells us that by raising Jesus from the dead on the first Easter God promises to raise us from the dead as well. If we trust God to keep this promise, then we can face death with faith.

Skeptical Doubt

Now, a skeptic might complain. “Ah, you Christians! This false belief is just one more form of the denial of death. There is no God. There is no resurrection. There is no reason for faith.” Now, does such skepticism precipitate anxiety?

Ernest Becker considered all of this. He weighed alternatives. The Christian promise, thought this Jewish thinker, looks better than the alternatives.

Becker believed that institutionalized religion, specifically Christianity, is the best mode of satisfying our urges. God is the perfect Beyond because God is abstract and therefore malleable and not so easily falsifiable. “Religion answers directly to the problem of transference by expanding awe and terror to the cosmos where they belong. It also takes the problem of self-justification and removes it from the objects near at hand. We no longer have to please those around us, but the very source of creation — the powers that created us, not those into whose lives we accidentally fell.”

Christianity is also ideal because it turns our self-hatred and guilt of our creatureliness into a condition for salvation. Thus spake Ernest Becker.

Conclusion

When I was eighteen years old, these questions weighed heavily on me. At that time I read the poem, Thanatopsis, by William Cullen Bryant (1794-1878). Bryant was only a young man when he wrote it in 1817. Whenever I conclude my ponderings about this subject, I like to conclude as Bryant did in Thanatopsis.

So live, that when thy summons comes to join

The innumerable caravan, that moves

To that mysterious realm, where each shall take

His chamber in the silent halls of death,

Thou go not like the quarry-slave at night,

Scourged to his dungeon, but, sustained and soothed

By an unfaltering trust, approach thy grave,

Like one who wraps the drapery of his couch

About him, and lies down to pleasant dreams.

▓

Ted Peters is a Lutheran pastor and emeritus professor at the Graduate Theological Union. He co-edits the journal, Theology and Science, with Robert John Russell on behalf of the Center for Theology and the Natural Sciences, in Berkeley, California, USA. His single volume systematic theology, God—The World’s Future, is now in the 3rd edition. He has also authored God as Trinity plus Sin: Radical Evil in Soul and Society as well as Sin Boldly: Justifying Faith for Fragile and Broken Souls. See his website: TedsTimelyTake.com.

He has just published a new 2023 book, The Voice of Public Theology, to be published by ATF Press.

▓

Becker, Ernest. 1973. The Denial of Death. New York: Free Press.

D’Souza, Dinesh. 2009. Life Beyond Death: The Evidence. Washington DC: Regnery.

Pagels, Elaine. 2020. Why Religion? A Personal Story. New York: Ecco.

Peters, Ted. 1993. Sin: Radical Evil in Soul and Society. Grand Rapids MI: Wm B Eerdmans.