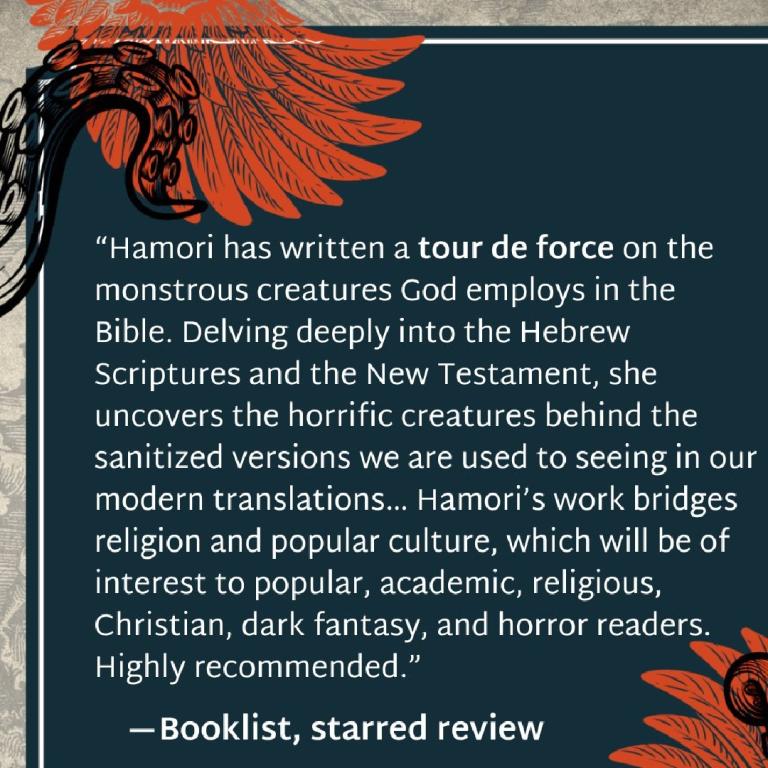

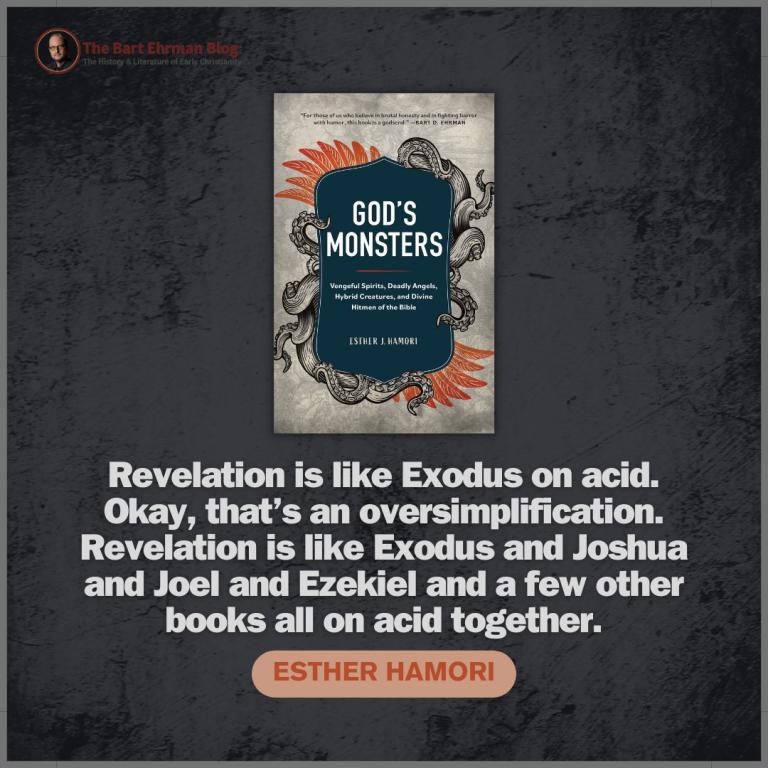

The Bible is full of monsters, some of which you’ll recognize, and some of which you didn’t realize were monsters before reading Esther Hamori’s book God’s Monsters: Vengeful Spirits, Deadly Angels, Hybrid Creatures, and Divine Hitmen of the Bible (Broadleaf, 2023).

I am a biblical scholar and read or listen to a lot of books related to biblical studies, both those aimed at scholars and those aimed at a general audience. As someone whose main field is New Testament but who also writes on the intersection of religion and popular culture, I can genuinely say that I learned from Hamori’s book God’s Monsters and that it is by far one of the best examples of public scholarship that I have ever come across. I experienced it as an audiobook and the narrator captured the volume’s seriousness and humor, including the moments of deep penetrating sarcasm, just perfectly. There’s no way I could ever do justice to the humor, and trying to would probably spoil them at any rate. Much of the humor comes in the form of pop culture references. The analogies and contrasts with angels, demons, and other monsters from film and television are not just a bridge between the scholarship and the wider audience. They serve to clarify the points made and to make the experience of learning about biblical literature in its Ancient Near Eastern and Mediterranean context all the more enjoyable. I was glad that Doctor Who got a mention. Even when pop culture is referenced, however, the focus is on the Bible in its ancient context. So many times I was struck by things I had missed that I feel like listening to the audiobook again to remind myself of them all. I’ll offer as one example the way that both the Song of Songs’ description of the beloved and God’s description of Leviathan in the Book of Job fall into the same genre of poem, expressing love and admiration. In more than one place in the Bible, it is Leviathan rather than human beings that represents the pinnacle of God’s creation.

What I will say is that even if you have significant familiarity with the Bible you’ll still come to understand seraphim and various other monsters in the divine entourage differently and better, and that you’ll wrestle as well with the monstrosity of God. Hamori pulls no punches and explicitly compares the apologetic attempts to claim that God deserves to get off the hook no matter what God does to President Nixon claiming that if the president does something then it’s right even if illegal. It may make you uncomfortable, but that is because the portrait of God and God’s army of henchmen has been so sanitized and domesticated that hearing someone speak about it so honestly and clearly is at times shocking. The book’s humorous side, rather like God’s loving side in the Bible, does not undermine the full expression of the book’s serious side, such as when Hamori wrestles with the way monsterization, especially in traditions about gigantism, forms a deadly rationale for genocide and conquest from ancient times down to the present day. The ways that Hamori compares God to Sheldon Cooper, Col. Jessup from A Few Good Men, and other fictional characters are simultaneously entertaining, provocative, and insightful.

Read this book. You’ll be learning and laughing out loud constantly. It’s a book that you won’t want to put down once you start. No one who reads it will be sorry they did. I’m grateful for what Hamori has provided in this important and engaging volume. If you, like me, have a particular penchant for snarkasm and appreciate when others use it effectively, you are the ideal audience for this book. I am seriously thinking that I should develop a course on religion and monsters, the Bible and monsters, or perhaps more controversially God, Angels, Demons, and Other Monsters. I would definitely use Hamori’s book as a textbook. Have any other readers of my blog taught or taken a course like that? If so, I’d love to hear about it. (I found one taught by Mona LaFosse whom I don’t know. I’m glad her university made a libguide for her course!)

I posted a shorter version of this review on Amazon. I will add that unlike many books that I review, this one was not sent to me by the publisher. It just looked like it was worth reading so I did. Hopefully that will add to your sense that this is a genuinely unbiased review.

See also the reviews by Anne Thériault and Bob Cornwall, the short recommendation by Brandon Grafius, and the brief comments by Bart Ehrman after which follow a guest post by Hamori (one of several). There is also a brief video with Dan McClellan, and Conor Hilton’s review is worth checking out for the picture alone. I hope that my friends like Steve Wiggins, Doug Cowan, and John Morehead who are interested in horror in a way that I am not will explore and perhaps review Hamori’s book as well as utilize it in their own teaching and scholarship.

The episode

The episode

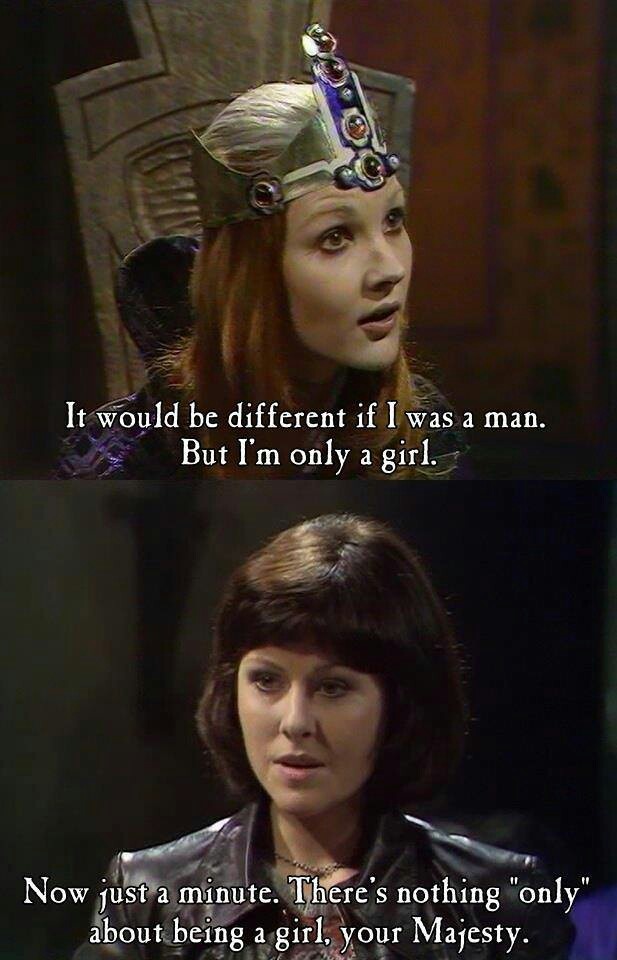

Throughout much of the episode, Kronos seems like little threat to the universe. When Kronos appears, what we see looks rather like a person pretending to be a deranged chicken flapping about. But at the end of the episode, when the Doctor, Jo, and the Master find themselves caught in between their own reality and that in which Kronos resides, Jo mistakes it for heaven. Then, Kronos appears as a giant female face, and she says that just as she is beyond gender, so she is beyond good and evil, and can be destroyer, healer, or creator.

Throughout much of the episode, Kronos seems like little threat to the universe. When Kronos appears, what we see looks rather like a person pretending to be a deranged chicken flapping about. But at the end of the episode, when the Doctor, Jo, and the Master find themselves caught in between their own reality and that in which Kronos resides, Jo mistakes it for heaven. Then, Kronos appears as a giant female face, and she says that just as she is beyond gender, so she is beyond good and evil, and can be destroyer, healer, or creator. DOCTOR: Jo, would you condemn anybody to an eternity of torment? Even the Master?

DOCTOR: Jo, would you condemn anybody to an eternity of torment? Even the Master?