Are we really doing this again/still/forever?*

Sigh. OK.

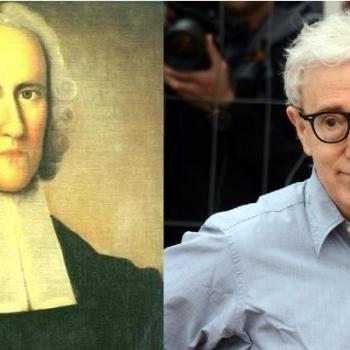

Jonathan Edwards was a man of his time. That’s true for everyone, of course, other than, say, Dr. Sam Beckett or Billy Pilgrim. What this phrase usually means, though, is that the “man of his time” is someone who was complicit in the injustices and evils of his time. It’s a form of the sometimes legitimate objection we often raised as kids: “Why should I be punished when everybody else was doing the same thing?”

We weren’t entirely wrong to point that out to our teachers: Singling out one person for something unexceptional seems unfair. But we overstated our case with that superlative “everybody.”

It’s rarely ever the case that “everybody” was doing the same thing. Most people, perhaps, or surely “many others” — enough to make the behavior in question unexceptionally commonplace. Yet usually there are exceptions — others who are also people of that time believing and behaving differently. The past may be a foreign country, but no country is a homogenous collection of identical people behaving identically.

But let’s not be abstract: We’re talking about slavery. Here in America, talk of someone being a “man of his time” is almost always about slavery.

Thus, in the case of the slave-owning pastor and theologian Edwards, I have often noted this:

[The abolitionist] Benjamin Lay lived from 1681 to 1759. Somehow a person like Lay is never described as “a man of his time.” And yet we’ll apply that description to his contemporaries — like, say, Jonathan Edwards (1703-1758) — to excuse them for being unable to know any better. Edwards was a man of his time. He was also a man of Benjamin Lay’s time, and of John Woolman’s (1720-1772).

My objection there has been challenged by some historians who argue that it’s unfair and misleading to contrast Edwards with exceptional outliers like Lay and Woolman. Both were Quakers and were, in their lifetime, dissidents even with the limited realm of Quakerism. No fair comparing them as also being “men of their time” because they were actually “ahead of their time.”

But, of course, no one can actually be “ahead of their time” except for, again, someone like Sam Beckett or Billy Pilgrim (who are both, remember, fictional). What we mean by “ahead of their time” is that they were at odds with the majority of people in their time — that they were exceptional. It seems unfair to condemn someone for not being exceptional or for — like most people “of their time” — failing to heed the exceptional voices that 20/20 hindsight allows us to realize were right. (This is why Luke 16:29-31 must give these professional historians the heebie-jeebies.)

Hence Dr. John Fea’s insistence that Edwards’ time was almost wholly devoid of any anti-slavery voices of any consequence. He quotes Manisha Sinha’s The Slave’s Cause: “With few exceptions, Western thinkers had justified rather than challenged slavery”** and thus, Fea says, those seeking anti-slavery contemporaries to Jonathan Edwards “are pretty much left with Anthony Benezet, John Woolman, and the cave-dwelling dwarf Benjamin Lay.”

Well, sure, it’s possible to dismiss Benjamin Lay as a fringe figure with little or no influence because he was an irascible, theatrical, cave-dwelling dwarf but please re-read this sentence. Is there anything about Lay there that makes you less interested in him? Anything about being a “cave-dwelling dwarf” that makes you want to pay less attention?

Lay’s friend, admirer, and sometimes publicist, Benjamin Franklin helped to publish Lay’s All Slave-Keepers Apostates.*** That anti-slavery jeremiad was widely rejected, rather than widely embraced, but the key point here is the widely, not the rejected. Lay was notorious for causing scenes and he was very good at it. He was infamous but not un-famous. I’d bet that Edwards had heard of him and was at least vaguely aware of Lay’s argument.

But that doesn’t matter. Benjamin Lay is completely beside the point. So are Woolman and Benezet.

The dispute between Dr. Fea and his uppity bête noire on Twitter isn’t about the extent to which Edwards may or may not have encountered the dissenting arguments of those “few exceptions” among “Western thinkers.” The dispute, rather, is about the meaning of the incontrovertible fact that Edwards absolutely did encounter the dissenting witness of Venus, and Titus, and Joseph, and “Sue … wife to the said Jo.” They lived in his house.

This, I humbly submit, is the actual point of contention even though it is something neither Dr. Fea nor his interlocutor succeeds in articulating. I think that’s why they wind up wound up, angrily talking past one another without ever achieving disagreement.

The dispute is not about what it means that Edwards was a “man of his time,” but about what it means that Joseph was a also a man of Edwards’ time. It’s about whether, or how, Joseph’s life matters.

We cannot say that Edwards could not have known better because we cannot say he was of a generation that knew not Joseph. I’m quoting there from the King James Version of Exodus 1:8. Edwards stands indicted because, in the words of the NIV translation of that same verse, he was someone “to whom Joseph meant nothing.” If Joseph matters, too, then he merits the same empathy and generosity thus far denied him by those so intent on extending those lovely sentiments towards the man who enslaved him.

Or, as historian Malcolm Foley wrote in an essay I quoted here a few months ago:

I am reminded of the voices that call prominent theologians in the eighteenth and nineteenth century “men of their times” when referring to their virulently racist pro-slavery stances. It is not an imposition of a foreign standard that I apply when I call those stances virulently racist; it is the recognition and elevation of a standard contemporary to their own, namely that of the enslaved.

Jonathan Edwards was intimately acquainted with this standard contemporary to his own. He lived with (at least) four people who shared it.

Edwards is best known today for his most famous sermon, “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God.” The published version of this sermon is the one he read from when he delivered it on July 8, 1741, in Enfield, Connecticut. Four days earlier, in New York City, an enslaved Black man was burned at the stake.

This was part of the New York Conspiracy of 1741, a mass panic that began in April of that year resulting in show trials and dozens of public executions continuing throughout the spring and summer. The official death toll includes 13 enslaved men burned at the stake, 17 enslaved persons hanged, and two white men and two white women hanged after being named as participants in the purported conspiracy. That doesn’t include the countless others beaten, tortured, or killed by mobs of white New Yorkers convinced that a mass slave uprising was imminent.

The prosecution’s case was based largely on the testimony of one person who had been caught with stolen goods and was promised leniency (and financial reward) in exchange for naming names. All other evidence was the product of duress. The consensus view, today, is that there was no conspiracy and no slave revolt. It was simply a panic sparked by the fear — and the expectation — of such a revolt. It was mass hysteria based on the white majority’s recognition of the alternative standard contemporary to their own. They reasonably and rationally feared that the 10% of New Yorkers living in slavery would seek to revolt — to free themselves and to avenge the harms done to them — because that is what 100% of New Yorkers understood is what anyone would do in their circumstance.

Jonathan Edwards was likely aware of the chaos consuming New York City. It was big news in New England, where people still chafed at the mockery New Yorkers had directed toward them for decades after the debacle of the Salem witch trials. One New Englander — a Plymouth judge named Josiah Cotton — sent an anonymous letter to a lawyer involved in prosecuting the supposed “conspiracy.” Cotton’s letter chides the lawyer by comparing the city’s panic to that in Salem: “This occasion puts me in mind of our New England Witchcraft in the year 1692 Which if I don’t mistake New York justly reproached us for, and mocked at our Credulity about.”****

But, again, it doesn’t matter one way or another whether or not Edwards was aware of the 1741 Panic in New York. Either way, we know what he knew, what all of those terrified white New Yorkers knew. “Every white man there [had] this thought stowed somewhere or other in his mind. … It was a kind of secret which [they] all knew and were too clever to tell.”

*See previously:

- 6.20.14: Our job is to unlearn the lies we learned from the theologians of slavery

- 6.21.14: Unlearning the lies we learned from the theologians of slavery (part 2)

- 6.26.14: Unlearning the lies we learned from the theologians of slavery (part 3)

- 7.9.14: Whatever happened to the clobber texts for slavery? (Unlearning the lies, cont’d.)

- 8.21.14: The Hole in Noll: The whiteness of ‘[White] America’s God’

- 1.26.16: Slaves in the hands of an angry white God

- 4.18.16: What if we learned about the Bible from the people who got it right?

- 3.12.18: The Half Has Never Been Told

- 8.8.18: George Whitefield was worse than Hybels, Swaggart, Haggard, Patterson, Pressler, Bakker, Hinn, Tilton and all the rest put together

- 2.4.19: Bad Reputation: The right subject, the wrong question

- 2.8.19: ‘It was a kind of secret which we all knew and were too clever to tell’

- 2.10.19: If ‘we’ didn’t know, now ‘we’ know

- 2.13.19: Never been partial to shackles or chains

- 9.6.20: Most 21st-century white evangelicals oppose child-trafficking and rape. That’s new.

- 11.13.21: Father Abraham had many sons

- 3.15.22: ‘Onesimus’

- 8.22.22: No time like the present

** “Western” is, in this sentence, a limiting, qualifying, restrictive term. It bounds the parochial realm within which slavery was justified, rather than challenged, by “thinkers.” Note also that the immediately following sentence begins with the word “but”: “With few exceptions, Western thinkers had justified rather than challenged slavery. But popular prejudice against slavey had long been prevalent, at least since the collapse of serfdom in western Europe. Notions of inherent racial inferiority served to counter this sentiment.”

I’m not sure that Sinha is saying what Fea thinks here.

*** Full title: “All Slave-Keepers That keep the Innocent in Bondage, Apostates, Pretending to lay Claim to the Pure & Holy Christian Religion; of what Congregation so ever; but especially in their Ministers, by whose example the filthy Leprosy and Apostasy is spread far and near; it is a notorious Sin, which many of the true Friends of Christ, and his pure Truth, called Quakers, has been for many Years and still are concern’d to write and bear Testimony against; as a Practice so gross & hurtful to Religion, and destructive to Government, beyond what Words can set forth, or can be declared of by Men or Angels, and yet lived in by Ministers and Magistrates in America.” Phew.

**** Cotton goes on to say, “I entreat you not to go on to Massacre and destroy your own Estates by making Bonfires of the Negros and perhaps thereby loading yourselves with greater Guilt than theirs. For we have too much reason to fear that the Divine Vengeance does and will pursue us for our ill treatment to the bodies and souls of our poor slaves.”

So here, too, we find another contemporary witness to the then-evident evil of slavery.