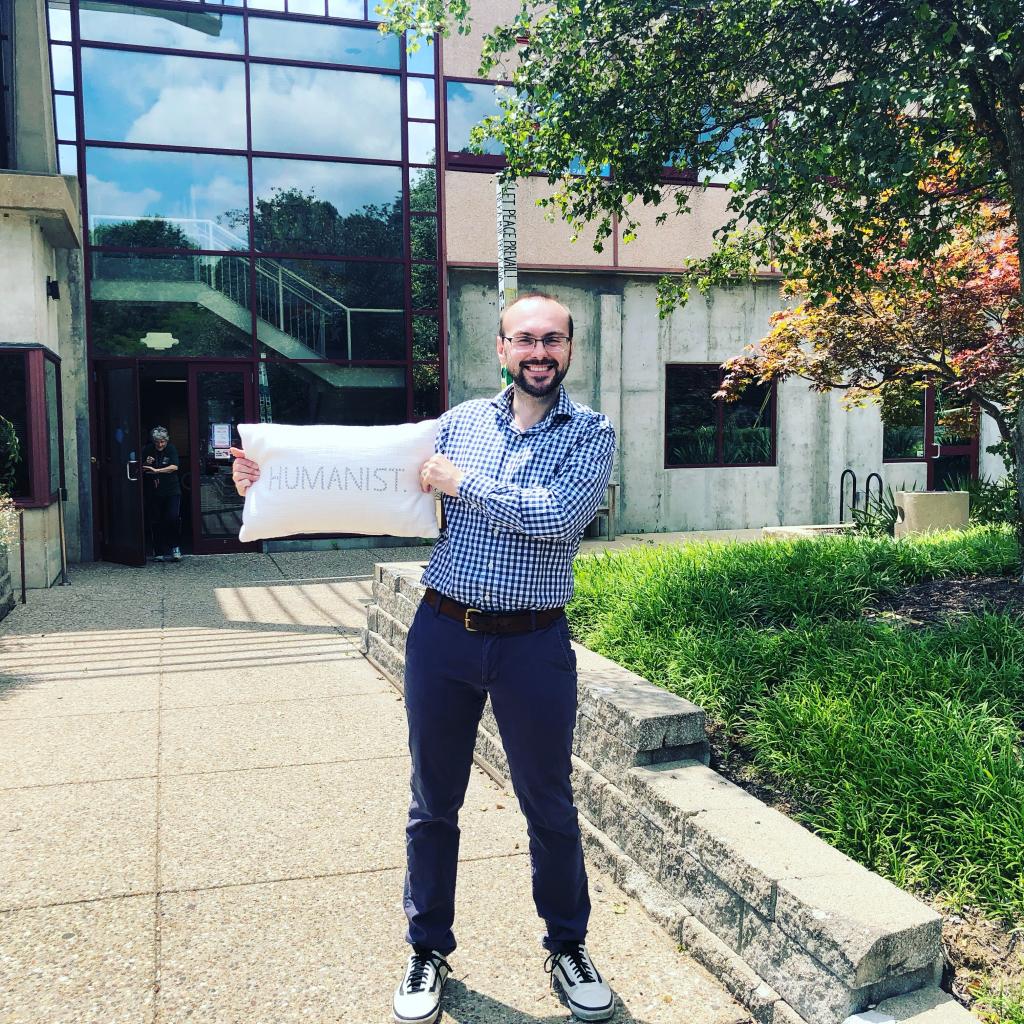

I moved to St. Louis in June of 2014. I moved across the country, leaving the leafy walks of Harvard Yard and the coastal air of Boston, to a city I knew almost nothing about in a state I’d hardly ever visited, to do a job I had never done: I was to train as clergy for the Ethical Society of St. Louis, a Humanist congregation. I didn’t know whether I’d enjoy the city or the work. I was giving up friendships and stepping away from the academic path I had walked for seven years. I was motivated by the desire to help people directly with my philosophical training, to use Humanist ideas to help people live better lives and to improve society – but I wasn’t certain this was the right way to do it. It was a leap of faith. Hah.

On August 9th, 2014 – not two months since I had moved to the city – Mike Brown was shot and killed by Darren Wilson, and the city exploded. I wasn’t in town on the day of the shooting, or during the immediate aftermath, but I read the news and knew instantly that the Ethical Society had to take a stand. The Ethical Society of St. Louis was founded to uphold the equal dignity and worth of every person, and in my mind being shot and killed for the “crime” of walking in the street is not consistent with that principle. No unarmed person should end up dead after an encounter with the police.

But I was new to my position, and I was an intern (a paid, full-time intern, but still), someone training to be clergy but not clergy yet. I didn’t feel sure about taking a strong position on behalf of an of an organization I had just joined, when I knew there would potentially be backlash. It became very clear very quickly that many white St. Louisans were not on board with the protests, and that taking a clear position could cause some major problems. It is a tough thing to help lead a community through a crisis, especially when the community is split. Ultimately, though, I simply felt that no organization could call itself an “ethical society” without fighting for the right of people of color not to be summarily executed by agents of the state. It was foundational, for me: if we weren’t for Mike Brown, we weren’t for equal dignity, and that would make us hypocrites.

So the moment I got back into to town I started to attend organizing meetings with local clergy. We’d gather in church basements and halls and plan how we, representatives of the city’s faith community, would respond. This was not an easy thing: there were mixed feelings about the role of clergy in the protests, and differences of view among the clergy themselves. We were navigating political differences, theological differences, and personal differences. There were some experienced protesters among us, and some who were very nervous. There were some experienced protesters who were very nervous: the police had been nasty, and there were definite risks.

But quickly a series of actions were planned, then more, then yet more. The orange vests of activist clergy became a common sight on the streets of St. Louis, as we knelt in roadways, joined hands in city streets, rallied in public squares, hosted panel discussions and storytelling evenings and teach-ins. For a time I went to multiple actions a day, just going where the protests were. I volunteered with jail support, helping track people through the system, making sure we knew where our activist siblings were and hoping they were safe. I wrote articles and spoke when requested; I stayed silent and followed when asked. I did my best to be useful.

During my post-Ferguson activism I saw some of the most disgraceful behavior I could have imagined from police, politicians, and members of the public. Worse than I could have imagined. Police routinely acted in aggressive and illegal ways, brutalizing activists for no good reason. I saw people dragged from wheelchairs; glasses smashed; faces bloodied; children choked; teargas canisters fired into buildings; activists effectively kidnapped by police; politicians revel in open racism; police representatives relentlessly politicize their response to the protests; citizens driving their cars through groups of protesters; activists – friends – sporting incredible police-inflicted wounds.

I did not think this was supposed to happen. I was raised to think police were helpers, if not universally benign then at least generally reliable. I was raised to believe that our political and criminal justice systems were basically functional: there were problems, to be sure, but nothing that a bit of reform wouldn’t fix. I was raised to believe that my job was to wield my education and my intellect to tweak an essentially friendly system, so that it became ever more friendly – to push things a little further toward progress. The police response to Ferguson – and the reaction of so many of my friends – burst the white liberal bubble of my upbringing and brought me face to face with the unpleasant reality of the world.In a few intense and unpleasant weeks, I learned that many of my assumptions about the world were simply wrong, a function of my upbringing, class, and status rather than a universal condition of humankind.

My main reaction was rage. I was furious that the system I had been prepared to participate in was revealed to be a sham. It was a deep and troubling anger, ever-present, keeping me from sleep. After a three days of sleepless nights I decided to see a therapist, thinking I could maybe talk through my anger. But it didn’t help – my problem was not that I was seeing things that weren’t there, such that dispelling the illusions would bring peace. Rather, I was for the first time seeing things as they really are, trying to come to terms with the fact that much of my prior life was was lived in an illusion. I met Mysterio.

I think activists sometimes find it hard to understand why so many smart, well-meaning people seem unable to see the systemic injustices which shape society. Why don’t decent white people see racism? Why don’t decent straight people see homophobia? Why don’t decent men see sexism? I understand this all too well: to recognize how unjust is our society is to appreciate how much of our own lives is shaped by unearned privileges. If I were to really confront how advantaged I have been by my whiteness, my level of economic comfort, my education, my maleness, then what is left of me? Which achievements could I claim for myself? And if I were to truly confront how brutally society treats people on the margins, what sort of world am I living in? Why would I want to live in that world, a world of bias and cruelty and hate? When the world without illusions is more horrible than you can imagine, who would want to be disillusioned? I understand why Cypher chose to stay in the Matrix.

Of course there is another side to this: disillusionment let’s you see what’s real, and it’s only when we see what’s real that we can effect true change. Disillusionment is a precursor to liberation. Cypher was the villain for a reason: he chose comfort over truth, and never found freedom. That’s why, despite how much I hated it at the time, I thank the Ferguson activists for dispelling my illusions. I see clearer now – even if I’m never as comfortable. It is better to know you have to climb a mountain than to falsely believe you have to vault a molehill – only the former will get us to the mountaintop. But wow is it hard to wake from a dream into a nightmare.

This post is part of a series of ten reflections on (roughly) ten years in the USA. Find the series here.