This information used to be in Chapter 2 of my book, but unfortunately I had to cut it due to length. (I initially worried about my ability to write a book that was at least 40,000 words, and then I wrote one that was 55,000 words!)

So, lucky you, I’ve turned it into a blog post instead. You can use this whenever someone tries to claim, for example, that the Catholic Church forbids women from working outside the home absent grave necessity (and yes, I’ve seen that very argument perpetuated).

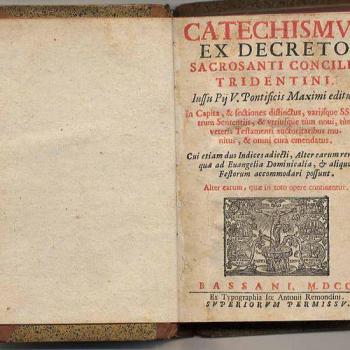

What Does the Catechism Say?

The Catechism of the Catholic Church (CCC) is silent about working mothers. If it was such a cardinal sin for women to work outside the home, you’d think the Catechism would mention it at least once, wouldn’t you? However, it doesn’t — but it talks quite a lot about the responsibilities of parents.

In its section about the domestic church, the Catechism says (emphasis mine):

It is here that the father of the family, the mother, children, and all members of the family exercise the priesthood of the baptized in a privileged way “by the reception of the sacraments, prayer and thanksgiving, the witness of a holy life, and self-denial and active charity.” Thus the home is the first school of Christian life and “a school for human enrichment.” Here one learns endurance and the joy of work, fraternal love, generous – even repeated – forgiveness, and above all divine worship in prayer and the offering of one’s life.

Nowhere does the Catechism say that a mother must forego employment and stay at home in order to properly facilitate the domestic church. On the contrary, part of the duties of parents is to teach their children the joy of work, among other virtues that can be lived out in the workplace as well as in the home.

Paragraph 2208 states:

The family should live in such a way that its members learn to care and take responsibility for the young, the old, the sick, the handicapped, and the poor. There are many families who are at times incapable of providing this help. It devolves then on other persons, other families, and, in a subsidiary way, society to provide for their needs: “Religion that is pure and undefiled before God and the Father is this: to visit orphans and widows in their affliction and to keep oneself unstained from the world.”

Part of caring and taking responsibility for the young, the old, the sick, the handicapped and the poor entails supporting them financially, or providing healthcare or health insurance. It could also include working as a physician, a nurse, or medical support personnel.

A few paragraphs down, there is the section detailing the responsibilities of parents to their children. The CCC does not say that a mother has the responsibility to stay at home with her children; on the contrary, it says:

Parents’ respect and affection are expressed by the care and attention they devote to bringing up their young children and providing for their physical and spiritual needs. As the children grow up, the same respect and devotion lead parents to educate them in the right use of their reason and freedom.

Providing for one’s children’s physical needs can include providing financially by working outside the home (and part of providing for their spiritual needs could be working outside the home in order to afford Catholic school tuition).

The section titled Economic Activity and Social Justice, starting at paragraph 2426, discusses man and his relationship and responsibilities within the economic sphere.

In work, the person exercises and fulfills in part the potential inscribed in his nature. The primordial value of labor stems from man himself, its author and its beneficiary. Work is for man, not man for work.

Everyone should be able to draw from work the means of providing for his life and that of his family, and of serving the human community.

Everyone has the right of economic initiative; everyone should make legitimate use of his talents to contribute to the abundance that will benefit all and to harvest the just fruits of his labor. He should seek to observe regulations issued by legitimate authority for the sake of the common good.

Not just men, not just single women or married women without children, but everyone.

Further on, the Catechism says:

2433 Access to employment and to professions must be open to all without unjust discrimination: men and women, healthy and disabled, natives and immigrants. For its part society should, according to circumstances, help citizens find work and employment.

Nothing in this paragraph indicates that mothers should not utilize access to employment and professions.

A just wage is the legitimate fruit of work. To refuse or withhold it can be a grave injustice. In determining fair pay both the needs and the contributions of each person must be taken into account.

“Remuneration for work should guarantee man the opportunity to provide a dignified livelihood for himself and his family on the material, social, cultural and spiritual level, taking into account the role and the productivity of each, the state of the business, and the common good.”

Agreement between the parties is not sufficient to justify morally the amount to be received in wages.

It’s pretty clear from the context of the Catechism that “man” refers to “mankind” — as in all human beings, not just those of the male variety — hence, this paragraph of the CCC affirms that all men and women, which includes fathers and mothers of young children, should have the opportunity to provide for his or her family.

What Do the Popes Say?

Those who claim the Catholic Church teaches that mothers should not work like to pull quotes from older papal encyclicals — usually those published prior to 1960 or so — out of their proper context to justify their claims.

Women in general and working mothers in particular are only mentioned very briefly in Pope Leo XIII’s encyclical about human work, Rerum Novarum, published on May 15, 1891:

Women, again, are not suited for certain occupations; a woman is by nature fitted for home-work, and it is that which is best adapted at once to preserve her modesty and to promote the good bringing up of children and the well-being of the family.

In that particular day and age, it was rare for a woman, especially a mother, to work outside the home. Working mothers of that era usually kept their economic activity firmly centered in the home. In rural areas, they raised livestock for sale or sold animal by-products (eggs, milk, cheese, honey, wool, etc.), made and sold baked goods, made and sold clothing, wove cloth or created lace, raised and sold garden produce, and so on.

In more urban locales, women often worked alongside their husband in a family business such as a mercantile or a restaurant, or sometimes owned a business themselves. (In this case, the children usually pitched in to work as soon as they were old enough, and young children stayed alongside their mother as they worked.) Some took in boarders to earn extra income. The wife of a doctor might work as a receptionist in his home office, or even as a medical assistant or nurse.

Thus, Pope Leo noted that women were “fitted for home-work” — which does not preclude them earning a wage — and emphasized that the well-being of the family must be paramount.

When you consider the incredible amount of work it took to ensure the well-being of one’s family, and the amount of effort required to keep a family adequately clothed and fed without the benefit of electricity, running water, or indoor plumbing, it’s hard to argue that both parents could successfully work outside the home without their family suffering, or without family support — for example, elderly relatives — to take over needed tasks.

He doesn’t elaborate on what occupations women are suited for, or say that women (single or married) must not be engaged in any occupation. Otherwise he would have had to condemn Saint Zelie Martin, mother of Saint Therese of Lisieux, who ran a successful lace-making business with her husband, Saint Louis Martin, circa 1858.

Pope Pius XI spoke about working mothers in his encyclical Casti Connubii, which was promulgated on the last day of 1930 (all emphases mine):

The same false teachers who try to dim the luster of conjugal faith and purity do not scruple to do away with the honorable and trusting obedience which the woman owes to the man. Many of them even go further and assert that such a subjection of one party to the other is unworthy of human dignity, that the rights of husband and wife are equal; wherefore, they boldly proclaim the emancipation of women has been or ought to be effected. This emancipation in their ideas must be threefold, in the ruling of the domestic society, in the administration of family affairs and in the rearing of the children. It must be social, economic, physiological: – physiological, that is to say, the woman is to be freed at her own good pleasure from the burdensome duties properly belonging to a wife as companion and mother (We have already said that this is not an emancipation but a crime); social, inasmuch as the wife being freed from the cares of children and family, should, to the neglect of these, be able to follow her own bent and devote herself to business and even public affairs; finally economic, whereby the woman even without the knowledge and against the wish of her husband may be at liberty to conduct and administer her own affairs, giving her attention chiefly to these rather than to children, husband and family.

Again, note how the pope’s concern is not necessarily with the fact that the mother is working, but rather if the mother is working to the detriment or neglect of herself, her husband, and/or her family. He expresses concern about a working mother who is working in defiance of the preference of her husband, or who devotes all of her time to work and none to her husband and children, or who literally abandons her home and family in order to work. And he decries the “false teachers” of that day and age (for example, Margaret Sanger, founder of what is now Planned Parenthood) who told married wives and mothers that they could or even should do any or all of those things in order to be “liberated” women.

Another favorite quote used to decry working mothers is from Pope Pius XI’s Quadragesimo Anno, promulgated in 1931:

In the first place, the worker must be paid a wage sufficient to support him and his family.[46] That the rest of the family should also contribute to the common support, according to the capacity of each, is certainly right, as can be observed especially in the families of farmers, but also in the families of many craftsmen and small shopkeepers. But to abuse the years of childhood and the limited strength of women is grossly wrong. Mothers, concentrating on household duties, should work primarily in the home or in its immediate vicinity. It is an intolerable abuse, and to be abolished at all cost, for mothers on account of the father’s low wage to be forced to engage in gainful occupations outside the home to the neglect of their proper cares and duties, especially the training of children. Every effort must therefore be made that fathers of families receive a wage large enough to meet ordinary family needs adequately. But if this cannot always be done under existing circumstances, social justice demands that changes be introduced as soon as possible whereby such a wage will be assured to every adult workingman. It will not be out of place here to render merited praise to all, who with a wise and useful purpose, have tried and tested various ways of adjusting the pay for work to family burdens in such a way that, as these increase, the former may be raised and indeed, if the contingency arises, there may be enough to meet extraordinary needs.

Initially, this certainly sounds like Pope Pius XI is condemning working mothers, doesn’t it? However, note that he says mothers should work — not “must work” or “may only work” — in the home or its immediate vicinity. “Should” allows for extenuating circumstances. Also consider some of these points:

- This encyclical was written in 1931, at a time when the Great Depression had crippled most of the world’s economies. Many men and women were forced into physically exhausting jobs that had long hours and paid very little just to keep their families fed. This fact was at the forefront of the pope’s mind when he decried the low wages, insufficient to support a family, being earned by fathers.

- The jobs available to women at that time were few, and to married women, even fewer — in fact, in the United States in 1930, 26 states had laws prohibiting the employment of married women, and the federal government had passed a law stating that married women could not be employed in government jobs.

- As discussed previously, the household responsibilities of women at that time lacked the utilities and labor-saving devices we have access to today, meaning that keeping a family adequately fed and clothed took much more time and effort. A mother working full-time outside the home in that day and age would barely have time for sleeping and eating herself with all of the work there was to do at home, just keeping up with her family’s basic needs.

In both encyclicals, this is the underlying message that Pope Pius XI conveys: it isn’t that mothers should never work, it’s that her “outside” work should not cause her to ignore or neglect her vocation as a wife and mother.

This message is again repeated in Divini Redemptoris, published by Pope Pius XI in March 1937:

Refusing to human life any sacred or spiritual character, such a doctrine logically makes of marriage and the family a purely artificial and civil institution, the outcome of a specific economic system. There exists no matrimonial bond of a juridico-moral nature that is not subject to the whim of the individual or of the collectivity. Naturally, therefore, the notion of an indissoluble marriage-tie is scouted. Communism is particularly characterized by the rejection of any link that binds woman to the family and the home, and her emancipation is proclaimed as a basic principle. She is withdrawn from the family and the care of her children, to be thrust instead into public life and collective production under the same conditions as man. The care of home and children then devolves upon the collectivity. Finally, the right of education is denied to parents, for it is conceived as the exclusive prerogative of the community, in whose name and by whose mandate alone parents may exercise this right.

To put this excerpt in its proper historical context, Divini Redemptoris was an anti-Communist encyclical. Pope Pius XI is, again, not condemning mothers who work; he is criticizing the the role of women in the political system of Communism (women had no choice in the matter and were expected to work alongside men, even if they did not want to do so, while the care and education of the children was taken over by the government — what better way to brainwash the next generation?).

As you can see, when read in the appropriate context, these excerpts do not condemn working mothers in and of themselves — rather, they condemn any situation or system in which a mother’s employment, necessary or otherwise, leads to the neglect of one’s home and family.

Over time, the role of mothers in the workforce become more prominent and plausible, thanks to the invention of labor-saving devices such as dishwashers, washers and dryers, electric ovens and microwaves, ready-made fabrics and clothes, and so on.

Once mothers were much better able to manage the responsibilities of their homes and families in addition to a job outside the home — and as more and more husbands stepped up to share in those responsibilities — so too did the doctrine of the Church develop as pertains to working mothers.

Pope John XXIII said in his 1963 encyclical Pacem et Terris (emphasis mine):

The conditions in which a man works form a necessary corollary to these rights. They must not be such as to weaken his physical or moral fibre, or militate against the proper development of adolescents to manhood. Women must be accorded such conditions of work as are consistent with their needs and responsibilities as wives and mothers.

Pope Saint John Paul II said the following in 1981:

In this context it should be emphasized that, on a more general level, the whole labour process must be organized and adapted in such a way as to respect the requirements of the person and his or her forms of life, above all life in the home, taking into account the individual’s age and sex. It is a fact that in many societies women work in nearly every sector of life. But it is fitting that they should be able to fulfil their tasks in accordance with their own nature, without being discriminated against and without being excluded from jobs for which they are capable, but also without lack of respect for their family aspirations and for their specific role in contributing, together with men, to the good of society. The true advancement of women requires that labour should be structured in such a way that women do not have to pay for their advancement by abandoning what is specific to them and at the expense of the family, in which women as mothers have an irreplaceable role.

Here, Pope John Paul II echoes what Pope Pius XI had said some fifty years previously: Having to abandon these tasks in order to take up paid work outside the home is wrong — not intrinsically, or by its nature, but instead when it contradicts or hinders these primary goals of the mission of a mother.

Indeed, the pope puts the onus on employers and society to structure the work of women in such a way that it does not interfere with their vocations as wives and mothers.

In Familiaris Consortio, also published in 1981, he has an entire section on “Women in Society” where he addresses the issue of working mothers. Specifically, he says,

…in the specific area of family life a widespread social and cultural tradition has considered women’s role to be exclusively that of wife and mother, without adequate access to public functions which have generally been reserved for men…. There is no doubt that the equal dignity and responsibility of men and women fully justifies women’s access to public functions.

and

…the true advancement of women requires that clear recognition be given to the value of their maternal and family role, by comparison with all other public roles and all other professions. Furthermore, these roles and professions should be harmoniously combined, if we wish the evolution of society and culture to be truly and fully human.

Fourteen years later, in his 1995 Letter to Women, he takes special care to thank women who work — and he doesn’t say that his words are only addressed to women without children at home.

Thank you, women who work! You are present and active in every area of life-social, economic, cultural, artistic and political. In this way you make an indispensable contribution to the growth of a culture which unites reason and feeling, to a model of life ever open to the sense of “mystery”, to the establishment of economic and political structures ever more worthy of humanity.

This sentiment was echoed by then-Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger — later Pope Benedict XVI — in May 2004 (emphasis mine):

In this regard, it cannot be forgotten that the interrelationship between these two activities – family and work – has, for women, characteristics different from those in the case of men. The harmonization of the organization of work and laws governing work with the demands stemming from the mission of women within the family is a challenge. The question is not only legal, economic and organizational; it is above all a question of mentality, culture, and respect. Indeed, a just valuing of the work of women within the family is required. In this way, women who freely desire will be able to devote the totality of their time to the work of the household without being stigmatized by society or penalized financially, while those who wish also to engage in other work may be able to do so with an appropriate work-schedule, and not have to choose between relinquishing their family life or enduring continual stress, with negative consequences for one’s own equilibrium and the harmony of the family. As John Paul II has written, “it will redound to the credit of society to make it possible for a mother – without inhibiting her freedom, without psychological or practical discrimination and without penalizing her as compared with other women – to devote herself to taking care of her children and educating them in accordance with their needs, which vary with age.”

Pope Francis said in his apostolic exhortation Amoris Laetitia:

Here I would also like to mention the situation of families living in dire poverty and great limitations. The problems faced by poor households are often all the more trying. For example, if a single mother has to raise a child by herself and needs to leave the child alone at home while she goes to work, the child can grow up exposed to all kind of risks and obstacles to personal growth. In such difficult situations of need, the Church must be particularly concerned to offer understanding, comfort and acceptance, rather than imposing straightaway a set of rules that only lead people to feel judged and abandoned by the very Mother called to show them God’s mercy. Rather than offering the healing power of grace and the light of the Gospel message, some would “indoctrinate” that message, turning it into “dead stones to be hurled at others”.

Pope Francis also spoke specifically about working mothers during a visit to the campus of an Italian university:

Another challenge emerged from the voice, of this good working mother, who also spoke on behalf of her family: her husband, her young son and the baby she is expecting. Hers is an appeal for employment and at the same time for her family. Thank you for this testimony! In fact, it is about trying to reconcile working hours with family time.

Not only did Pope Francis praise a “good working mother,” during this address, he urged employers to help their employees balance their responsibilities with flexible schedules and time off.

In my upcoming book, I also talk about the teachings and examples of the saints — such as St. Zelie, St. Teresa Benedicta of the Cross, a.k.a. St. Edith Stein, St. Elizabeth Ann Seton, and St. Gianna Beretta Molla.

I don’t have a firm release date yet, but I know it will be mid-May 2019. As soon as pre-ordering is available, I will let you know!