This post was recently posted on Facebook by someone I know and I was added to the link. I want to deal with this here because it is not only something this other person does all the time, but it is a really common occurrence when arguing about morality and moral claims. I have talked about all the things I will talk about here very frequently, but I will try to draw them all together in several pieces (I will link to a lot of my previous articles so not to make this series massively long, even though it already is!). I was commissioned by John Loftus a few years back to write a chapter on exactly this subject for his anthology Christianity Is Not Great (link to my series drawing on my chapter). My views will be split over several pieces.

Without further ado, here is what he said:

HOW NOT TO ARGUE – KNIFE CRIME AS EXAMPLE One can approach knife crime as a baffling and inexplicable phenomenon that could be happening on another planet. One can commission studies that address it at the statistical level as if it is a mathematical phenomenon to be solved by the stats. But this is to adopt a very particular behaviourist approach which looks at human behaviour in terms of surface appearances. To do this is to adopt a very specific model of what a human is. So, correlations between school exclusions, money invested in youth clubs, unemployment etc will give you the ‘answers’ (they usually involve blaming the Government of the day). The answer, then is to apply money at the place indicated by the stats. Anyone who quarrels with this is hit over the head with studies considered to have the privileged last word on the matter, called unscientific, a refuser of ‘evidence’, naive, bad or even mad.

However, the very distinctive, statistical behaviourist approach strangely excludes a vital element from the phenomenon we are supposedly examining and one with which, being human ourselves, we are all familiar. It excludes moral interiority, responsibility and agency in the carrier of the knife, the very things that differentiate us from animals and because of which every sophisticated society has courts assuming moral accountability. Strange things to blink at you might think. The interesting this is that a person who has no expertise in behaviourist data collection and statistics can see this from the viewpoint of their simple humanity. So what value the statistical approach if the statisticians haven’t even considered the full nature and parameters of what they are studying?

I don’t want to discuss the causes of knife crime here. I don’t want to insist on proving the existence of moral responsibility. I simply want to point out the faultiness of the argumentative methodology. Those who adopt the purely statistical, behaviourist approach (which may garner some interesting information) should have the good manners to ask if their interlocutors feel this method is satisfactory and addresses the whole picture. The very adoption of that model shapes the conclusion by excluding key avenues in human nature at the outset. What value, then, does the experiment have? It’s studying a phenomenon by assuming at the outset that it has a different nature from what it actually has.

I simply use this as an example of how the behaviourist approach to the problem is as much up for discussion as its conclusions are. To exclude the moral may be one of the reasons for the problem. Shouting at the sceptic who doubts the methodology because the statistics prove the case is vain as the issue is, can statistics prove the case here?

It’s interesting that David Lammy’s approach in 2012, where he put knife crime down to the moral vacuum created by paternal absenteeism, might address the moral issue better.

Essentially, we shouldn’t look at data concerning behaviour and concentrate on internal moral causality. And by this, he also means devaluing the biosocial jigsaw of causality that causes moral behaviour. This is merely morality, absent, it appears, of any other causal influence so that it can just be the domain of the agent (uncaused) in its causality. As you can tell, we have argued the toss over free will.

This guy is a moral deontologist who believes in free will and God (though in a much more traditional, British and conservative sense than in any evangelical American sense). He is a pretty standard conservative who believes that morality exists inside people as a driver and he would here is two things that look very similar to a form of essentialism. I remember when we were arguing at Tippling Philosophers that he felt quite strongly about gender norms in a very sensualist manner quite similar to natural law theory and to Thomistic philosophy.

These sorts of comments should sum him up:

As in leaving out the moral element in humans which can’t be reduced to data

And I don’t need books to tell me that morality exists here and now. I and you and everyone else can’t do without it in our daily discourse. It’s like saying I need a book to convince me I need oxygen. All I need is the accoutrements of my present humanity. That’s my authority [This is not to say he isn’t well-read – JP]

I start from the my engagement with the real as all real philosophers do.

It’s part of our essence. Your quotations prove it. The moment you criticise Trump for being a fascist.

So on and so forth. You get the idea. One of his favourite philosophers is Roger Scruton who is a pretty standard conservative deontologist.

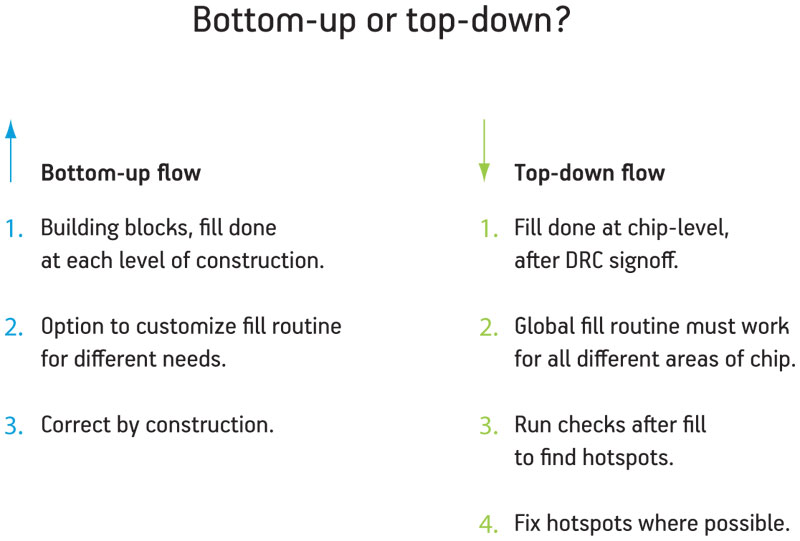

Bottom-Up and Top-Down

He takes great pleasure in disagreeing with pretty much everything I say. Part of this is because we disagree on pretty much all our conclusions by coming at things fro completely different angles.

The problem, as far as I’m concerned, is that he argues from his conclusions and not to them. This is one of the main points on want to make today. I wrote an article many years ago entitled “Top down or bottom up?“:

This is fundamental, in many senses, to me. It is why I spend a lot of time trying to establish the building bricks of philosophy, such as “what is an abstract idea?” So often we argue on the veneer, and so often this means that our conclusions or claims are propped up with little more than biases and bluster.

For me, the bottom-up approach is by far the more justifiable one.

If you look at this image about chip design (or something, it doesn’t really matter), you will get my point:

Here you can see that the left-hand approach has a conclusion which is correct if the whole thing is built correctly. The importance is in the construction, which should ensure truth if built with the correct bricks. The right-hand option smacks of ad hoc. If it doesn’t seem to work (is true) then just mess around with fixing things at the last stages, working under the assumption, nothing more, that the initial building blocks and desires and plans are correct.

At the end of the day, looking down on things is pretty arrogant, and assumes that you know best.

Abstract Objects

To argue that morality is just inside of us like some kind of magic fairy dust is merely wishful thinking and ends up being just an assertion. He doesn’t even really offer any proper deontological arguments. But that’s beside the point. Let’s look at the ontology as a whole. We know from the Philpapers survey that, even after 3000 years of moral philosophising, we are at an impasse for moral philosophers. No one single moral framework fully works. They are all problematic. This is why no one can agree. Indeed, any philosopher who coherently argued indubitably for a fully working moral framework would get the Nobel Prize. It hasn’t been done and it won’t be done.

And it can’t be done.

Morality is the ultimate of abstract objects. In order to understand the nature of morality, we need to understand the nature of abstract objects. What this comment does is to confuse actions that he has ascribed to moral value to with morality. But to ascribe something abstract to something concrete is quite a jump and needs some explaining, but this explaining is never ever done. Actions are themselves events with real, physical properties. Intentions are different to actions in that they are states of minds, but we know that the mind supervenes on the brain, the physical.

Mind – Brain Supervenience

There are several ways to show this:

1)The evolution of species demonstrates that development of brain correlates to mental development. E.g. “We find that the greater the size of the brain and its cerebral cortex in relation to the animal body and the greater their complexity, the higher and more versatile the form of life” (Lamont 63). Lamont, Corliss. The Illusion of Immortality. 5th ed. New York: Unger/Continuum, 1990.

2) Brain growth in individual organisms:

“Secondly, the developmental evidence for mind-brain dependence is that mental abilities emerge with the development of the brain; failure in brain development prevents mental development (Beyerstein 45). Beyerstein, Barry L. “The Brain and Consciousness: Implications for Psi Phenomena.” In The Hundredth Monkey. Edited Kendrick Frazier. Buffalo, NY: Prometheus Books, 1991: 43-53.

3) Brain damage destroys mental capacities:

“Third, clinical evidence consists of cases of brain damage that result from accidents, toxins, diseases, and malnutrition that often result in irreversible losses of mental functioning (45). If the mind could exist independently of the brain, why couldn’t the mind compensate for lost faculties when brain cells die after brain damage? (46).” Ibid

4) EEG and similar mechanisms used in experiments and measurements on the brain indicate a correspondence between brain activity and mental activity:

“Fourth, the strongest empirical evidence for mind-brain dependence is derived from experiments in neuroscience. Mental states are correlated with brain states; electrical or chemical stimulation of the human brain invokes perceptions, memories, desires, and other mental states (45).” Ibid

5) The effects of drugs have clear physical >>> mental causation.

Merely reading into Phineas Gage should open one’s eyes, here.

Back to Abstracts

Everyone who reads this blog regularly will know that it’s one of my favourite topics. That’s because it underwrites pretty much everything. And this is what I mean about arguing from the bottom up. If you don’t establish what abstract ideas are, pretty much the rest of philosophy is just preference. It arguing from a conclusion that you like but it’s not building up to a conclusion. It is a castle in the sky.

Morality is an abstract idea, so surely we would need to know what an abstract idea is and what its ontology (principles of existence) is? As many of you know, I am a conceptual nominalist.

Nominalism arose in reaction to the problem of universals, specifically accounting for the fact that some things are of the same type. For example, Fluffy and Kitzler are both cats, or, the fact that certain properties are repeatable, such as: the grass, the shirt, and Kermit the Frog are green. One wants to know in virtue of what are Fluffy and Kitzler both cats, and what makes the grass, the shirt, and Kermit green.

The realist answer is that all the green things are green in virtue of the existence of a universal; a single abstract thing that, in this case, is a part of all the green things. With respect to the color of the grass, the shirt and Kermit, one of their parts is identical. In this respect, the three parts are literally one. Greenness is repeatable because there is one thing that manifests itself wherever there are green things.

Nominalism denies the existence of universals. The motivation for this flows from several concerns, the first one being where they might exist… Particular physical objects merely exemplify or instantiate the universal. But this raises the question: Where is this universal realm? One possibility is that it is outside of space and time…. However, naturalists assert that nothing is outside of space and time. Some Neoplatonists, such as the pagan philosopher Plotinus and the philosopher Augustine, imply (anticipating conceptualism) that universals are contained within the mind of God. To complicate things, what is the nature of the instantiation or exemplification relation?

Conceptualists hold a position intermediate between nominalism and realism, saying that universals exist only within the mind and have no external or substantial reality.

Moderate realists hold that there is no realm in which universals exist, but rather universals are located in space and time wherever they are manifest. Now, recall that a universal, like greenness, is supposed to be a single thing. Nominalists consider it unusual that there could be a single thing that exists in multiple places simultaneously. The realist maintains that all the instances of greenness are held together by the exemplification relation, but this relation cannot be explained.

Finally, many philosophers prefer simpler ontologies populated with only the bare minimum of types of entities, or as W. V. Quine said “They have a taste for ‘desert landscapes.’” They attempt to express everything that they want to explain without using universals such as “catness” or “chairness.”

As ever, the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry on nominalism is great – here. As is the SEP entry on abstract objects – here. As is the superb SEP entry on properties found here. Other useful SEP entries are Challenges to Metaphysical Realism, Platonism in Metaphysics, and the wiki entry on the Third Man Argument (an argument from Plato that shows an incoherent infinite regress in relational universals, which can be found in the SEP here).

To illustrate this, let’s now look at the “label” of “chair” (in a very cogent way, all words are abstractions that refer to something or another, but nominalists will say that these abstractions, or the relationship between them and the reference points, do not exist, out there, in the ether). This is an abstract concept, I posit, that exists, at most, only in the mind of the conceiver. We, as humans, label the chair abstractly and it only means a chair to those who see it as a chair—i.e. it is subjective. The concept is not itself fixed. My idea of a chair is different to yours, is different to a cat’s and to an alien’s, as well as different to the idea of this object to a human who has never seen or heard of a chair (early humans who had never seen a chair, for example, would not know it to be a chair. It would not exist as a chair, though the matter would exist in that arrangement). I may call a tree stump a chair, but you may not. If I was the last person (or sentient creature) on earth and died and left this chair, it would not be a chair, but an assembly of matter that meant nothing to anything or anyone.[i] The chair, as a label, is a subjective concept existing in each human’s mind who sees it as a chair. A chair only has properties that make it a chair within the intellectual confines of humanity. These consensus-agreed properties are human-derived properties, even if there may be common properties between concrete items—i.e. chairness. The ascription of these properties to another idea is arguable and not objectively true in itself. Now let’s take an animal—a cat. What is this “chair” to it? I imagine a visual sensation of “sleep thing”. To an alien? It looks rather like a “shmagflan” because it has a “planthoingj” on its “fdanygshan”. Labels are conceptual and depend on the conceiving mind, subjectively.

What I mean by this is that I may see that a “hero”, for example, has properties X, Y and Z. You may think a hero has properties X, Y and B. Someone else may think a hero has properties A, B and X. Who is right? No one is right. Those properties exist, in someone, but ascribing that to “heroness” is a subjective pastime with no ontic reality, no objective reality.

This is how dictionaries work. I could make up a word: “bashignogta”. I could even give it a meaning: “the feeling you get when going through a dark tunnel with the tunnel lights flashing past your eyes”. Does this abstract idea not objectively exist, now that I have made it up? Does it float into the ether? Or does it depend on my mind for its existence? I can pass it on from my mind to someone else’s using words, and then it would be conceptually existent in two minds, but it still depends on our minds. What dictionaries do is to codify an agreement in what abstract ideas (words) mean, as agreed merely by consensus (the same applies to spelling conventions—indeed, convention is the perfect word to illustrate the point). But without all the minds existing in that consensus, the words and meanings would not exist. They do not have Platonic or ontic reality.

Thus the label of “chair” is a result of human evolution and conceptual subjectivity (even if more than one mind agrees).

If you argue that objective ideas do exist, then it is also the case that the range of all possible entities must also exist objectively, even if they don’t exist materially. Without wanting to labour my previous point, a “forqwibllex” is a fork with a bent handle and a button on the end (that has never been created and I have “made-up”). This did not exist before now, either objectively or subjectively. Now it does—have I created it objectively? This is what happens whenever humans make up a label for anything to which they assign function etc. Also, things that other animals use that don’t even have names, but to which they have assigned “mental labels”, for want of better words, must also exist objectively under this logic. For example, the backrubby bit of bark on which a family of sloths scratch their backs on a particular tree exists materially. They have no language, so it has no label as such (it can be argued that abstracts are a function of language). Yet even though it only has properties to a sloth, and not to any other animal, objectivists should claim it must exist objectively. Furthermore, there are items that have multiple abstract properties which create more headaches for the objectivist. A chair, to me, might well be a territory marker to the school cat. Surely the same object cannot embody both objective existences: the table and the marker! Perhaps it can, but it just seems to get into more and more needless complexity.

When did this chair “begin to exist”? Was it when it had three legs being built, when 1/2, 2/3, 4/5, 9/10 of the last leg was constructed? You see, the energy and matter of the chair already existed. So the chair is merely a conceptual construct. More precisely a human one. More precisely still, one that different humans will variously disagree with.

Let’s take the completed chair. When will it become not-a-chair? When I take 7 molecules away? 20? A million? This is sometimes called the paradox of the beard / dune / heap or similar. However, to be more correct, this is an example of the Sorites Paradox, attributed to Eubulides of Miletus. It goes as follows. Imagine a sand dune (heap) of a million grains of sand. Agreeing that a sand dune minus just one grain of sand is still a sand dune (hey, it looks the same, and with no discernible difference, I cannot call it a different category), then we can repeatedly apply this second premise until we have no grains, or even a negative number of grains and we would still have a sand dune. Such labels are arbitrarily and generally assigned so there is no precision with regards to exactly how many grains of sand a dune should have.

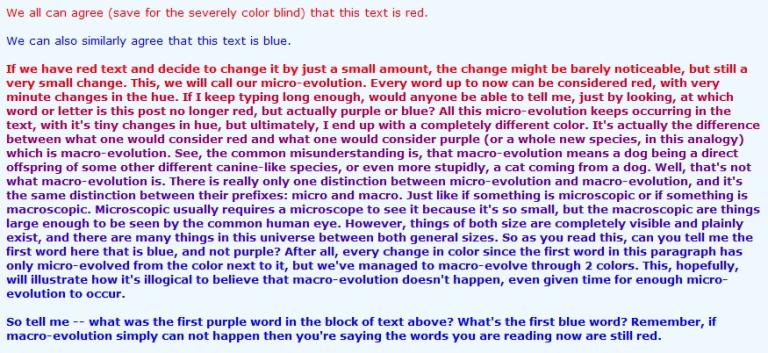

This problem is also exemplified in the species problem which, like many other problems involving time continua (defining legal adulthood etc.), accepts the idea that human categorisation and labelling is arbitrary and subjective. The species problem states that in a constant state of evolving change, there is, in objective reality, no such thing as a species since to derive a species one must arbitrarily cut off the chain of time at the beginning and the end of a “species’” evolution in a totally subjective manner. For example, a late Australopithecus fossilised skull could just as easily be labelled an early Homo skull. An Australopithecus couple don’t suddenly give birth to a Homo species one day. These changes take millions of years and there isn’t one single point of time where the change is exacted. There is a marvellous piece of text that you can see, a large paragraph[ii] which starts off in the colour red and gradually turns blue down the paragraph leaving the reader with the question, “at which point does the writing turn blue?” Of course, there is arguably no definite and objectively definable answer—or at least any answer is by its nature arbitrary and subjective (depending, indeed, on how you define “blue”).

End result? Realism is, in my opinion, untenable and conceptual nominalism (conceptualism) is not only a more coherent argument, it is also borne out by actual data and the world around us.

Here are a number of articles on abstract objects that you can read so that I don’t make this unnecessarily long:

- Philosophy fundamentals – abstracts and abstract ideas

- The Pertinence of Nominalism to Religious and Philosophical Debates

- Philosophy 101 (philpapers induced) – Abstract objects: Platonism or nominalism

- The “I”, personhood and abstract objects

- My Atheistic Moral Philosophy; Objective, Subjective and Theistic Morality

Morality – What Is It? Abstract.

But what this commenter needs to do is to establish some kind of ontic realism. This is why moral positions are often categorised into realism and anti-realism. But morality is a conceptual construct that we create in order to navigate the world as a social species. Without it, society would fall apart. That is precisely because society has been constructed using morality as both a tool and a currency. So when we both say it exists, there is some kind of equivocation.

- Races Do Not “Exist” Even Though They Might “Exist”

- Human Rights Don’t Exist until We Construct and Codify Them

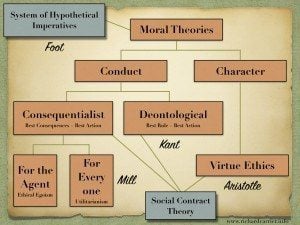

Let’s set out the basics. What is morality? Generally, the study of morality is split into three components: descriptive morality, meta-ethics and normative morality. Normally philosophers replace the term ‘morality’ with ‘ethics’. Descriptive ethics is concerned with what people empirically believe, morally speaking. Normative ethics (which can be called prescriptive ethics) investigates questions of what people should believe. Meta-ethics is more philosophical still in attempting to define what moral theories and ethical terms actually refer to. Or,

What do different cultures actually think is right? (descriptive)

How should people act, morally speaking? (normative)

What do right and ought actually mean? (meta-ethics)

Of course, this kind of philosophising is a prime example of an abstract past time! Descriptively, it seems fairly self-evident to me that moral skepticism is evident. The fact that no moral philosophy works perfectly, the fact that we all believe slightly different things of morality, shows that there is, descriptively, subjectivity concerning moral philosophy.

Either that, or it is hidden somewhere in the world or in the mind of God (see my article “16 Problems with Divine Command Theory ” for a big critique of such deontological ethics). The problem here is that we have to subjectively interpret it so it becomes subjective at any rate. As Kant said, we can’t know things-in-themselves. Add to that the fact that we can make huge errors in accessing this source of morality and you end up having a scenario where you have to construct them using moral reasoning anyway. Which is precisely what happens.

Deontology is the idea that there is some objective, mind-independent moral framework. If this can’t exist outside of sentient minds, then we have a problem. If all humanity or all sentient creatures were to die, then the concept of morality (the existence of morality) would die with those sentient creatures. Again, this is something I’ve talked about almost endlessly, it seems.

The basic point is that you simply can’t decontextualise morality. This is what deontology seeks to do and is doomed to failure. The enquiring murderer and other similar thought experiments put paid to this. Reductio ad absurdum of deontology leads to conclusions where deontologists would actually allow any number of horrible things to happen in the name of rigid morality. Kant’s Categorical Imperative is criticized because the instruction to create rules which should be universal is vague and subject to the potentially flawed opinion of anyone using it.

Richard Carrier writes a fantastic essay to show that all moral value systems defer to virtue ethics anyway: “Open Letter to Academic Philosophy: All Your Moral Theories Are the Same” (he argues for Goal Theory, which looks not too disimilar to desirism, in my opinion).

But what does this mean if morality is conceptual and not ontically real? Well, it means that these conceptual ideas like morality have to be constructed by minds. All minds are independent of each other but they have similar biological construction as well as cultural and historical similarities. Therefore, we often agree on things. However, we also often disagree. The only way of navigating this is to agree by consensus. And this is precisely what happens. This is how democracy works and how laws get written. You vote in a ruling party that can change the law based on a majority rule. Or you have some kind of dictatorship that doesn’t do this…

But in the most representative forms of government and society, we use consensus to work out how best to exist with each other. We use consensus to write dictionaries. We use consensus to make laws. We use consensus to make policies. So on and so forth. Otherwise, it is just might makes right. Historically, of course, this is precisely what happened before the Enlightenment period and the development of political ideals.

Conclusion

It is difficult to make any such article concise because as soon as you make one claim you have to then establish that by using something more fundamental and then establish that using something more fundamental. This is precisely why you have to start from the bottom and work your way up. I am having to do this again for the purposes of establishing why this commenter and myself disagree so often (and so I am sorry to my regular readers for massively repeating myself here!). I maintain that abstract ideas are conceptual (existing individually only in our minds and the minds of any sentience, higher-level thinking creature) and if we want to establish any abstract claims (such as morality and thus politics and regulation and law), we need to do so by consensus. This is both descriptively true, but is also evidenced by point of fact that no philosopher has fully and completely coherently established any moral value system.

In the next piece, I will look at this the earlier bio social jigsaw that leads to the development of moral behaviour. Just a little hint to get you going:

The second part can now be read here.

Stay in touch! Like A Tippling Philosopher on Facebook: