I recently posted a piece on objective morality in response to Jeremiah Traegar’s article here at ATP. In discussing my response elsewhere, there were the following points that I would like to deal with here in order to kill two birds with one philosopher’s stone.

My original quotes are in italic, with the commenter’s comments in blockquote.

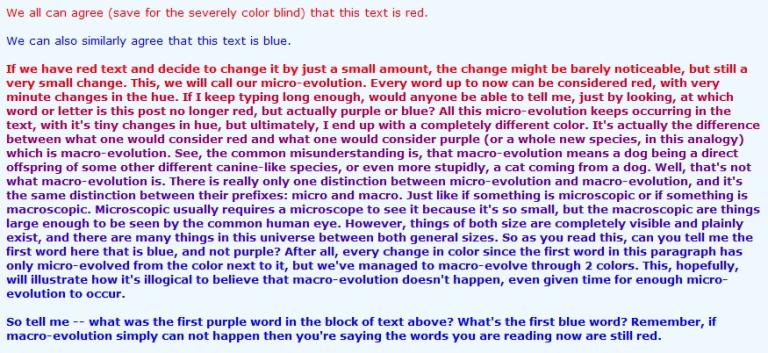

You can argue that there is an objectively better course of action given two options, A and B. If you are looking for wellbeing or happiness (for example), as your endgame for morality, then perhaps option B empirically gets you more of those things. However, setting that as your endgame is not an objective ideal. It is a subjective, conceptual ideal. I would add that for morality to make any coherent sense, for me at any rate, it needs to be goal-oriented, and setting those goals is a subjective project.

Why can’t some endgames be objectively better than others, merely in virtue of the nature of conscious beings and their capacity to suffer and flourish, independent of our beliefs about what we ought or ought not to do to others? Anyone who sets “causing abject suffering” as their endgame is doing morality worse than someone who sets “reducing abject suffering” as their endgame, it seems to me. Also, discovering which goal one ought to pursue need not be subjective, though it is often experienced this way. I think we can coherently say that some goals are objectively better than others for some people at some times.

Some endgames can objectively be better than others in terms of empirically evidenced outcomes. It’s just a sense of what is better that needs establishing objectively, and this is difficult. For example, and here we get into some standard criticisms of prima facie consequentialism, how do we objectively define a better outcome for wellbeing, even if we do establish that wellbeing is self-evidently good and therefore some kind of objective metric.?

What I mean by this is if we say that option B over option A for wellbeing is empirically better, how do we go about calculating this? Do we mean this for the person in question, or for multiple people? Which multiple people? And for how long should we look at the consequences? And what if wellbeing is positively affected in one way and negatively affected in another? When there are pluralistic methods or units of moral evaluation, who gets to define which one wins out? Is it intention or is it outcome? And the problem is, as far as I can tell, moral realism needs to be in some sense absolute. Morally real prescriptions that exist somewhere “out there”, or wrapped up self-evidently in the world, must be self-evidently true. There can be no grey that requires people to argue the toss over one option or another, one moral value system or unit over another. This would surely lead to a kind of subjectivism or conceptual approach.

Let me try to exemplify.

Imagine I give £5 to a homeless man. My intention is to make that person’s life better, and I have a rose-tinted view of what will happen. Perhaps I am being naive and my intentions are naive. Perhaps the burden is on me to make sure that that person spends the money wisely. Let’s park that for the time being.

Now imagine the homeless man (please excuse me from stereotyping – it’s just an example) spends it on crack cocaine for the first time, or Spice, or whatever. This starts him down a trail of self-destruction that massively hurts his family. He goes into a five-year downward spiral of addiction and crisis, destroying his wider family. His wife commits suicide and his children develop mental health issues.

So my intentions were good (but I could arguably have done a better job of researching or ensuring a better outcome), yet the outcome was bad.

For five years.

It then turns out that he turns his life around and makes an awesome recovery. He becomes a role model for ex-users and ends up making a huge contribution to society in stopping other potential addicts taking that route. We could now play the destruction and pain in his family off against the life-changing events to those potential addicts. Which events have more unitary power in terms of moral calculation? Is there an objective matrix of values that feed into some sort of moral calculation that can give you an objectively true analysis of a moral action?

Now, on a twenty-year outcome-based evaluation, that fiver was well spent. However, as a result of that fiver being given and his resultant addiction, let’s say he stopped becoming an ethical vegetarian. We are now playing one outcome against another, and we are not sure over what time period we cut off our evaluation.

And we could look at that event and see the whole matrix of events that would only have come about as a result of that fiver donation. After one hundred years, that fiver event could have affected billions of people. That’s the nature of causality and time.

Where do we cut time off and how wide a net do we evaluate?

It gets even worse if we take into account the counterfactuals.

What if we didn’t give him a fiver, but someone else would have given him a tenner? What if we hadn’t given him the money and as a replacement for that something happened that was either massively beneficial or negative for him? And what if these counterfactuals (or the original action from me) had really mixed outcomes for a mixed number of people? Our non-donation or actual donation can be seen in the context of not only what did happen, but also in terms of what didn’t happen.

But, you might say, morality is not evaluated by outcome. Okay, this sounds like some conceptual, abstract philosophy. We are arguably moving away from moral realism. Somehow, written into the fabric of the universe is moral obligation or law or evaluation based on our intentions: let’s say it is about desire and intention. But should my intention require some responsible analysis or can I be just as moral by going through life with a carefree hopeful attitude that all of my actions will lead to good outcomes? If I naively go through life thinking in terms of giving people fish rather than teaching them to fish, my intentions are good, but they may very well actually be naive and damaging.

And how do we link outcome to intentions? Surely outcome should in some way inform our intentions so that we have an idea of the success of our intentions and we can adapt our intentions accordingly. In other words, I can learn that my intentions are better if I responsibly research what the outcomes of my actions are or might be. Learning from outcomes that giving homeless people money is not as useful as giving them food or buying The Big Issue from them where possible means that I can intend to do better by having a better grip on the outcomes of my actions (I am not interested in whether this is actually true for the purposes of this point).

But I’m not sure that any of this helps an absolute sense of moral realism, notwithstanding problems of the actual ontology of abstract moral laws. And there is another area for discussion: are moral laws descriptive or prescriptive?

I struggle to be able to make sense of “objective” abstracta as mind-independent “things”, since all conceptual entities must, to my mind, be mind-dependent; they are things of the mind.

This is a classic struggle for modernists and postmodernists, as you lay out here. That said, secular folks seem to have no trouble making sense of the laws of physics as our attempts to describe actual features of reality that exist out there in a mind independent kind of way. The “law of gravity” is a ghost as Pirsig would say, it exists out there, but not like a thing, instead as a description of what is. We discover that description in our own subjective way, but it precedes us. Same goes with moral claims. The truth of the claim “slavery is wrong” exists out there just as much as the speed of light, long before anyone human figured out either. I don’t even think it’s that weird, just a category reification error, which was what Plato was trying to find is way through after all.

This sort of links well to the above. We discover the real properties of the world and then immediately subjectivise them. This is along the lines of Kant and his ding an sich; we cannot know things-in-themselves as everything is interpreted through our subjective sense experiences, and this would include morality. We produce our conceptual map of the real terrain but we must not confuse the map with the terrain.

Slavery is wrong when we do moral philosophising that starts with certain axioms, it’s just establishing those axioms and the resultant frameworks. But what about slavery in the natural world? Bee drones, which are all female, work to support and serve the queen and her progeny. Bee drones don’t actually consume honey. They rely on the queen’s grubs to secrete a substance to feed on. Thus they have no choice. The Polyergus Lucidus is a slave-making ant only found in the eastern United States. It is incapable of feeding itself or looking after its offspring without assistance and must parasitize members of its own species or close relatives in order to survive. It will raid other nests and carry the pupae away to be reared and eventually grow to become workers or, in this case, slaves in their own colony.

In a sense, all parasitic relationships in nature can be viewed as slavery. One organism benefits as a result of the work of another, and the working one receives no benefit and may be harmed.

We would need to establish, in terms of ontic realism, the term “slave” and to whom it precisely applies. This gets rather close to Wittgenstein and language. On this, he did a 180 flip in his philosophical life:

Wittgenstein’s shift in thinking, between the Tractatus and the Investigations, maps the general shift in 20th century philosophy from logical positivism to behaviourism and pragmatism. It is a shift from seeing language as a fixed structure imposed upon the world to seeing it as a fluid structure that is intimately bound up with our everyday practices and forms of life. For later Wittgenstein, creating meaningful statements is not a matter of mapping the logical form of the world. It is a matter of using conventionally-defined terms within ‘language games’ that we play out in the course of everyday life. ‘In most cases, the meaning of a word is its use’, Wittgenstein claimed, in perhaps the most famous passage in the Investigations. It ain’t what you say, it’s the way that you say it, and the context in which you say it. Words are how you use them.

So it becomes a case of working out the cut off point as to when slavery becomes wrong – it becomes an argument about personhood.

And, oh my, debates about personhood are precisely ones about realism and conceptual nominalism. I set this out in “What Is Personhood? Setting the Scene…“.

If moral realism supervenes on the idea of realism in terms of personhood, then it is doomed to failure.

Simply put, if there were no minds to conceive of morality, there would be no morality.

I might disagree, depending how you mean this. Morality tells us how we ought to treat sentient entities. As long as those sentient entities entities exist, the truths would apply to them, even if no one yet existed with a sufficiently advanced mind to cognize the those truths.

This starts to look like there might be agreement. Perhaps there is a greater need to define “objective morality” in the first place.

Again, I maintain that for these ideas to be existent in our brains the ideas are necessarily conceptual. We attach mental ideas to real properties of actions and events, and call this morality. But it is a conceptual affair. The tools and metrics we use to arrive at our conclusions will be real and empirical, though, it is just a case of establishing those frameworks themselves as ontologically objective.

[The commenter here is Aaron Rabi host of Philosophers in Space and Embrace the Void @etvpod podcasts. Check them out!]