In 2014, I’m reading and blogging through Pope Francis/Cardinal Bergoglio’s Open Mind, Faithful Heart: Reflections on Following Jesus. Every Monday, I’ll be writing about the next meditation in the book, so you’re welcome to peruse them all and/or read along.

This week’s chapter was more difficult than those previous for me. By the time I got up to this summary in the final pages, I was still at sea:

In summary, then, we are confronted with two rival projects. The first is the project of our faith that recognizes God as Father; this is the project that works for justice and makes us all brothers and sisters. The other project is the one proposed to us by the enemy acting as an angel of light; it is the project of the absent God, where humans prey on humans and the law of the strongest prevails: homo homini lupus. Which project will I choose? Am I able to distinguish one from the other? If I realize that I cannot discern between them, will I be astute enough to defend myself?

Unlike the last chapter, where Pope Francis used more concrete examples from day-to-day life (think of the woman making the priest walk to her house to bless it), a lot of this chapter stayed abstract and academic to me. Yes, we’re called to choose between God and the privation-thereof, check. But we’re also not so good at doing that, check. In order to read this chapter with more urgency, I kept reaching back to C.S. Lewis’s Screwtape Letters for examples of choices between desiring God and desiring the world that do sneak up on me.

But, given the distance at which I was reading the chapter, I didn’t know what to do with this:

When the enemy comes up against a faith that is by definition militant, he takes on the semblance of an angel of light and begins to sow seeds of pessimism. To engage effectively in any struggle, one must be fully confident of victory. Those who begin a struggle without robust confidence have already lost half the battle. Christian victory always involves a cross, but a cross that is the banner of victory.

Yes? I mean, I am technically confident that prodigal sons will be welcomed back if they choose to return and that God gives us a lot of opportunities to ask for grace and healing, no matter how far we’ve wandered. But that seems like confidence in the power of Christ to redeem us, not any particular confidence about which way I’m moving (world-wards or homewards) at the moment. So, being confident that there’s a way back doesn’t quite cure my pessimism that I might still be blundering in the opposite direction.

And I don’t find the comment about victory and the cross all that reassuring. As far as I understand, it means I shouldn’t assume that suffering is a cue that I’m on the wrong track, but it’s not exactly a polestar for the right path either. So that comment curbs one error of moral navigation but still leaves me lost.

Again, I’m reasoning a lot more about this chapter by pulling in outside sources. Pope Francis is writing primarily to priests, so talking about “discerning” brings up a richer array of references than just “deciding” or “judging.” I assume he’s referencing the Ignatian spirituality of his Jesuit order, which places an extraordinary emphasis on developing discernment (or, as an Aristotelian might put it, learning phronesis — practical wisdom). And, if you want to learn more about that, with more concrete examples and worked problems, I recommend a book that one of you recommended to me: Weeds Among the Wheat: Discernment Where Prayer and Action Meet by Thomas H. Green, S.J.

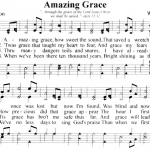

In my very abbreviated summary, discernment is the practice of sharpening your moral sense. By reviewing your actions after they pass (perhaps in a Daily Examen) and being mindful and alert to them as they occur, you can become increasingly sensitive to which actions make you a vessel of God’s love and which spill the graces out unused. Instead of only having a sense of how to choose when the options are stark, you are more able to recognize “the enemy acting as an angel of light” (as when you might want to speak sharply to someone who is underdressed for Mass — in the guise of reverence, you might be chasing someone away). And you may grow to notice more choices available in day to day life.

I can kind of see this theme resting below the text of this chapter, but, not being as steeped in discernment as I’d like, it’s a little too far away for me to grasp easily.

UPDATE: Gilbert gives his reading of this chapter at The Last Conformer