Don’t forget, if you’re in the Bay Area, that I’ll be speaking at St. Dominic’s this Monday night — tell your friends! And for those of you not near San Francisco, you can catch me on the radio at 5pm on Saturday or 1pm on Sunday.

I was really pleased to find, in the NYT artists imitating life (my life specifically). The paper interviewed Emma Stone and Eddie Redmayne in tandem, and, when asked how she persuaded her parents to let her try to be an actress, Stone said this:

ES: I made a PowerPoint presentation for my parents when I was 14. I asked them to let me move to L.A.

ER: On a computer?

ES: Yeah, all about why I should be an actor. I never wanted to do anything else, from 7 on. It wasn’t a flight of fancy. I asked to be home-schooled in a different presentation when I was 12. That was on a clipboard. I’m not kidding. I make presentations because when I feel strongly about something, I cry.

ER: You cry?

ES: When I feel really passionate, I get overwhelmed, and it makes me cry. I learned early on to be more logical and make presentations.

When I wanted to go to sleepaway summer camp, I polled my classmates about whether they were allowed to, made paper charts, and sat my parents down for a lecture. This wasn’t because I felt strongly enough to cry, but because I felt it would be wrong to ask if I didn’t have data of some kind to back me up. (I hadn’t previously asked and been turned down — I’m pretty sure the lecture was my first salvo, and they would have said yes without it).

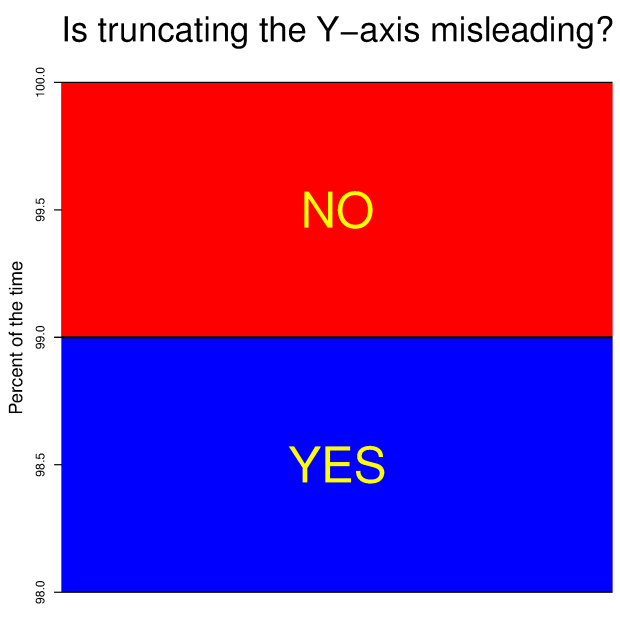

I should add, in the spirit of full disclosure, that I showed my parents misleading graphs. They were misleading in every way I knew how to make them so. The sample was not random, but was chosen from the most popular kids, who I figured were allowed to do anything. The pie chart had vivid colors for “Yes, allowed” and dull ones for “No” to make the “Yes” pop. And the Y-axis on the accompanying bar chart was truncated.

Which gives me the excuse to share my favorite truncated-axis graph with you — read it carefully!

And don’t fear for my parents. I was either scrupulously honest or counterproductively pleased with my own cunning — I walked them through both the graphs and why they were misleading.

Sticking with the theme of artful constructions (related to differing heights), I realized, when reading this article in the NYT Science section, that I’d never paused to wonder how fountains worked before electric pumps existed. Luckily someone else asked, and the NYT answered:

Beginning in ancient times, fountain designers relied on gravity, channeling water from a higher source in a closed system to provide pressure.

[…]

Just a few feet of elevation could provide enough water pressure for a satisfactory fountain spurt. Even comparatively primitive societies enjoyed such fountains, and recent research suggests the Maya may have done so.

At Versailles, the fountain complex ordered by King Louis XIV used a vast, complicated and highly expensive system of 14 huge wheels, each more than 30 feet in diameter, powered by the current of a branch of the river Seine. A river current is just another manifestation of the power of gravity.

Another neat construction project — the NYC medical examiner’s officer is having sculptors lay down (clay) flesh on casts of the skulls of unidentified murder victims, in the hopes of approximating their likenesses well enough to spark recognition. Think of them as 3D sketch artists. The article mentions a lot of interesting considerations, including:

Since relatives might remember the man through photographs, Mr. Palli said he sculpted the face with a slight smile, “because people usually smile in pictures.”

Speaking of making (necessarily limited) portraits of the dead, Kate Havard reviewed Diane Middlebrook’s Young Ovid for the Washington Free Beacon.

The Metamorphasis is full of stories of abrupt and violent change, and Middlebrook’s book itself is an example of life’s sudden and painful transformations. When she began the book, it was meant to be a full biography of the poet, but Middlebrook unexpectedly became ill and died before it could be completed. The resulting volume does not merely tell us about Ovid’s life: We also get, in a foreword by Middlebrook’s daughter and an afterward by her husband, a brief life of Middlebrook.

We read about Middlebrook teaching Ovid’s poetry for 30 years at Stanford, planning to make his biography her life’s achievement. When she discovers she is ill, her first response is to throw herself into the work, but she realizes that time will not allow her to finish it. At first, she despairs, but then her husband convinces her that what she has already written could be reworked into a book on the poet’s early life–his childhood, education, and the love affairs that inspired the Amores and the Ars Amatoria, love poems so explicit that they helped get Ovid exiled for immorality in 8 A.D., at the height of his fame.

Middlebrook winds up trying to intuit the experiences that underlaid Ovid’s art, and, as Calah Alexander makes clear in a recent post, it can be a big challenge to catch the pattern of someone else’s thoughts, even if that person is here to be interacted with:

Lincoln’s at that stage where communication is extremely important – not just saying words, but making himself understood. Unfortunately he’s still pretty difficult to understand, so reading is a great way to work on it, since I can usually figure out what he’s saying based on what he’s pointing at. But when we got to the “goodnight bears” page of Goodnight Moon, he started repeating something that I could not decipher.

It didn’t seem to have any relationship to the picture of the bears. He certainly wasn’t saying “bears”, “chairs,” or “goodnight”. I thought that maybe he was saying “mommy” because he was making an “m” sound, but when I pointed at the bear he was pointing at and said “mommy bear?” he said, “nope!” and kept repeating the same thing. At this point, I figured he was just trying to say a sentence or something, and tried the old “smile-and-nod-while-turning-the-page” trick.

That did not go over well. He insisted on turning the page back, then he started making a baffling motion with his fingers – a sort of tiny wiggling motion with his thumb and forefinger around the bears’ feet. The phrase he had been repeating seemed to get longer and increase in complexity, but it was still being repeated, because the same patterns of sounds were recurring.

You can discover what Lincoln turned out to be saying, and the lesson that Calah drew, over at her blog. (It’s charming)

And finally, also on communication, I’m sure I’ve mentioned before how much I like the song “Die Vampire Die” from [Title of Show]. Here it is again:

That song has the best (and briefiest) reframe for intrusive thoughts that I’ve seen:

Who do you think you’re kidding?

You look like a fool.

No matter how hard you try, you’ll never be good enoughWhy is it that if some dude walked up to me on the subway platform

and said these things, I’d think he was a mentally ill asshole,

but if the vampire inside my head says it,

It’s the voice of reason.

And in the final segment on this week’s This American Life, a man with anxiety turned out to find some piece by externalizing the incessant, unpleasant monologue in his head. He took notes on everything he worried about or felt ashamed about, and then wrote a script to have them randomly emailed to him.

So let’s imagine that I’m standing on the train. I’m about to go down into the train platform. And I look at my phone, and I have an email. And it’s from my anxiety.

I mean, here’s an email from June 2 in the afternoon. Now here’s the subject– history will forget you because history forgets people who are unable to finish anything. “Dear Paul, so you’re probably used to being at the front of the class, and this is a wake-up call that you’re not even in the middle. Inform me, are you ready? Sincerely, Your Anxiety.”

[…]

You can actually reply, right? I would reply and be like, go fuck yourself, over and over again. So the ability to actually yell back at something, which I think is something that we usually associate with being terrible on the internet, in this case, it’s wonderful, because you can yell at the robot and tell it to shut the fuck up.

I really recommend listening (it’s Act IV) or reading the whole segment; Paul’s story is vivid and a great real-life implementation of the “Die Vampire Die” approach.

For more Quick Takes, visit Conversion Diary!