The New York Times recently published a fascinating report on Brazilian Pentecostal “child preachers,” which it suggests is a major phenomenon. Without corroboration, Samantha Shapiro quotes a pastor who “estimates there are thousands” of evangelists and healers ages five to eighteen.

This is the sort of journalism of the weird and unusual that is one engine of mainstream coverage of religion in American newspapers. And it is fascinating!

The piece begins with a profile of Alani, the eleven-year-old daughter of pastor Adauto Santos who lives in São Gonçalo near Rio. Her parents share that she performed her first miraculous healing at the age of 51 days, when the touch of her hand relieved the distension in a woman’s stomach. Now she preaches, sings, and heals regularly, sometimes to drug addicts. Her classmates sometimes ask her to pray when they have headaches.

Child preachers are a fun subject. I first encountered Uldine Utley (immensely popular in the 1920s) in an article by Kristin Kobes du Mez published ten years ago [“The Beauty of the Lilies: Femininity, Innocence, and the Sweet Gospel of Uldine Utley,” Religion and American Culture 15 (Summer 2005).] Also, Thomas A. Robinson and Lanette D. Ruff wrote a book on the subject of girl evangelists in the 1920s, and they put together an accompanying website with a number of mini-biographies.

Du Mez describes Utley’s appeal as a counterpoint to the incessant masculinity and combativeness of 1920s fundamentalism. Born in 1912, Utley was converted at an Aimee Semple McPherson revival and went on her first evangelistic campaign at the age of eleven. She soon gained the support of fundamentalist preacher John Roach Straton, who at first “classed her with other boy and girl evangelists, some of whom I had seen and heard who could be justly classed as freaks.” Utley, by contrast, effortlessly moved between Bible passages in her sermons.

Du Mez describes Utley’s appeal as a counterpoint to the incessant masculinity and combativeness of 1920s fundamentalism. Born in 1912, Utley was converted at an Aimee Semple McPherson revival and went on her first evangelistic campaign at the age of eleven. She soon gained the support of fundamentalist preacher John Roach Straton, who at first “classed her with other boy and girl evangelists, some of whom I had seen and heard who could be justly classed as freaks.” Utley, by contrast, effortlessly moved between Bible passages in her sermons.

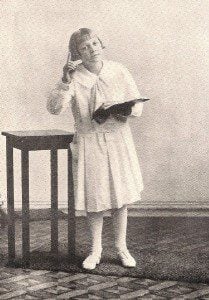

Audiences loved her “melodious voice” and “golden hair,” and she cultivated this ideal of femininity by dressing herself in white and carrying a single rose. Early in her ministry, she had a vision of a “mammoth rosebud” which unfolded petal by petal to reveal Jesus walking toward her. A good reminder that the visionary culture of American evangelicalism was alive and well in some quarters well into the twentieth century!

For a long while, Utley was a convincing portrait of childlike and feminine innocence, though later in her career some fundamentalists criticized her for cultivating a certain sex appeal. Some now termed her the a “Garbo in the pulpit.” It is not easy for child stars of any sort to grow up. Utley preached incessantly in the 1920s and into the 1930s, then had a breakdown in 1936 shortly after her marriage. The exact reasons for her breakdown remain unclear. Sadly, she was institutionalized for many decades prior to her 1995 death.

During her lifetime and since, detractors accused both Straton and Utley’s parents of exploiting their girl evangelist. Did her parents see her as the path to prosperity? In all likelihood, they worked her far too hard.

Shapiro presents the case of Victor Gabriel, who missed school but earned thousands while preaching at overnight conferences. Gabriel says that he does not regret his “lost childhood.” Also, Juanez Moraes, father of sixteen-year-old Matheus, promotes his son’s “career with the pride of a stage parent and also the shrewdness.” The family escaped a poor neighborhood to move into a gated apartment complex. Shapiro’s report is generally even-handed, but she strongly implies that greedy parents are exploiting their children.

The world of child preachers is quite foreign to my experience. We Presbyterians prefer ministers who have studied Greek and Hebrew over children (or adults) that speak in unknown tongues. Pint-sized preachers are not exactly doing things “decently and in order.”

The appeal, however, is not hard to see. Innocence. A clear sense of the miraculous, as children do things children are not expected to do according to their natural abilities.

There are clearly abundant examples of child preachers within early-American Pentecostalism and contemporary countries such as the Philippines and Brazil (and in some U.S. churches as well).

Children have surely long imitated parents, and child converts have surely long felt an urge to exhort and preach. Can any of our readers provide earlier examples?