I have been posting about some apocalyptic sayings attributed to the Prophet Muhammad, which are found in the collections known as the Hadith. Such sayings are numerous, and at so many points, they echo the lore found among contemporary Christians. Taken with those Christian documents, in fact, they suggest the depth of the apocalyptic fascination that inspired the Near East at this time, and which spanned faith boundaries. These documents might even have Christian origins.

Many of these texts are found in the collection known as Sahih Muslim, and specifically the section, “Pertaining To Turmoil And Portents Of The Last Hour” (Kitab Al-Fitan Wa Ashrat As-Sa’Ah). Here is a sample, which is striking for how closely it echoes the kind of ideas found in Christian apocalyptic at this time, and indeed long afterwards (The Dajjal is the Antichrist):

Hudhaifa b. Usaid Ghifari reported: Allah’s Messenger (may peace be upon him) came to us all of a sudden as we were (busy in a discussion). He said: What do you discuss ? They (the Companions) said. We are discussing the Last Hour. Thereupon he said: It will not cone until you see ten signs before and (in this connection) he made a mention of the smoke, Dajjal, the beast, the rising of the sun from the west, the descent of Jesus son of Mary (Allah be pleased with him), the Gog and Magog, and land-slidings in three places, one in the east, one in the west and one in Arabia at the end of which fire would burn forth from the Yemen, and would drive people to the place of their assembly.

(Translated by Abdul Hamid Siddiqui).

Jesus and the Judgment are both major components of the Qur’an, but the Turmoil and Portents deploy a whole apocalyptic mythology – the Antichrist, evil Jews, Gog and Magog – that looks very much as if it was borrowed from the Christian world in a later era. I do not believe most of the sayings in this section have anything to do with the historical Muhammad or his contemporaries, but rather fit the period somewhere between about 640 and 800, with the turbulent 740s and 750s an excellent candidate. Most of the borrowings would have come from the Syriac churches.

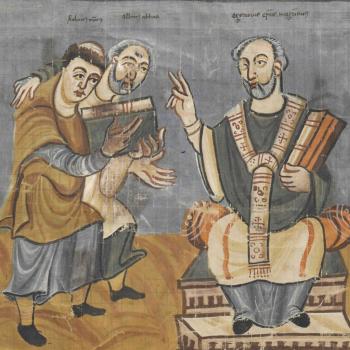

These Islamic texts coincide closely with a lively genre of Christian apocalyptic writing in the two centuries or so following the Arab Conquests. Repeatedly, Christians – presumably, monks and priests – used the genre of apocalyptic to describe the times in which they lived, and offer hope to their readers and listeners. In times of political conflict and repression, apocalyptic had the virtue of allowing anonymous and deniable commentary on current events. Commonly, these works were attributed to mighty sages and prophets of old. Daniel, for instance, was well known in the canonical Old Testament as a prophetic and apocalyptic figure, and Jews and Christians appropriated his name for many later texts. Enoch and Ezra were also popular mouthpieces. As these writings are “falsely attributed” or claimed, we call them pseudepigrapha.

In the seventh century, a Syriac Apocalypse of Daniel built on the Biblical text to depict the End Times and the Coming of Christ. Around 800, a Greek work of the same name describes the catastrophes that Christians will encounter at the hands of the sons of Hagar, the Arab Muslims, who ally with the Jews. Worldly disasters grow worse until the final Judgment and coming of Christ. “And with the Antichrist reigning and with the demons persecution, the Jews contriving vanities against the Christians, the great Day of the Lord draws near.”

Also in the seventh century, there appeared an Apocalypse of Ezra, “The Question of Ezra the Scribe while in the Desert with his disciple Karpos.” This work draws on the Revelation of John and the Book of Daniel, and neatly fits Islam into the apocalyptic framework. In the chaotic conditions of the 740s, Christian apocalyptic was deployed once again to portray the Umayyad Caliphs. As I have described, Enoch was the alleged author of an Apocalypse that envisioned the last Caliph.

One of the most influential and enduring of these texts was the Apocalypse of Pseudo-Methodius, which was firmly grounded in the Old Testament apocryphal scriptures. It offered a complete history of the world from the time of Adam, but it chiefly focused on conditions in the Muslim-dominated Near East around 690, which was presumably when it was written. “Methodius” foresaw the rise of a Greek King who would slaughter the Muslim Ishmaelites, reconquer Jerusalem, and liberate Christians, before the final Judgment. Reading such works, we see how they provide the context for the Islamic Turmoil and Portents. The main difference is that the apocalyptic signs and warnings are attributed not to some Old Testament prophet, but to Muhammad himself.

As I have suggested before, converted Christians, perhaps monks, were likely responsible for importing those apocalyptic traditions into Islam, so that the Turmoil and Portents might represent their handiwork. In my view, Turmoil and Portents represents a snapshot of Christian apocalyptic sentiment in the early-mid eighth century.

There is now quite a sizable literature on these themes, including:

Paul J. Alexander, ed., The Byzantine Apocalyptic Tradition (University of California Press, 1985).

Lorenzo DiTommaso, The Book of Daniel and the Apocryphal Daniel Literature (Brill, 2005).

Benjamin Garstad, ed., Apocalypse – Pseudo-Methodius (Harvard, 2012).

Sidney H. Griffith, The Church in the Shadow of the Mosque (Princeton University Press, 2008).

Matthias Henze, The Syriac Apocalypse of Daniel (Mohr Siebeck, 2001).

Robert A Kraft, Exploring the Scripturesque (Brill, 2009).

Andrew Palmer, ed., The Seventh Century in the West- Syrian Chronicles (Liverpool University Press, 1993).

John C. Reeves, Trajectories in Near Eastern Apocalyptic (Brill, 2006).

Zeki Saritoprak, Islam’s Jesus (University Press of Florida, 2014).

W. J. van Bekkum, Jan Willem Drijvers, and Alexander Cornelis Klugkist, eds., Syriac Polemics (Peeters, 2007).

Emeri van Donzel and Andrea Schmidt, eds., Gog and Magog in Early Eastern Christian and Islamic Sources (Brill, 2010).