Most semesters, I teach a course my university titled “Religions of the West.” Given my own background of research and writing, I at first considered pretending that the “West” meant the “American West” and having my students discuss Native American spirituality, Spanish missions, and Mormonism. Alas, “Religions of the West” meant the broader histories of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Sigh. Lots of work. But that’s why humanities professors get paid the big bucks.

Now, several years in, I’ve at least got the subject matter straightened out. But at the start of the semester, I ask my students consider why we are studying these three religions in tandem (I also question whether it makes sense to refer to them as “of the West”). What do they have in common? Monotheism? A significant role for written scriptures? Interconnecting scriptures?

At some point in this discussion, the term “Abrahamic religions” or “Abrahamic faiths” arises. Abraham is a significant figure for Jews, Christians, and Muslims.

Abram, whom God calls from Ur of the Chaldeans to the land of Canaan and with whom (renamed Abraham) God makes covenants long before the Mosaic law. Abraham’s covenant with God, made clear through the act of circumcision, establishes a relationship between God and a chosen people.

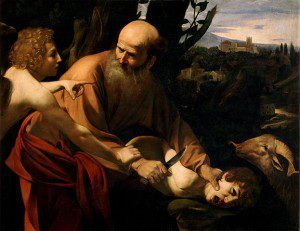

Abraham, of whom it was said, he “believed God, and it was reckoned to him as righteousness,” words written for our sake, because “it will be reckoned to us who believe in him who raised Jesus our Lord from the dead.” Abraham, willing to offer his son Isaac, prefigures God’s willingness to offer Jesus as an atonement for human sin.

Abraham, a prophet, who with his son Ishmael built (or rebuilt) the Kaaba, whose descendants through Ishmael included Muhammad, the seal of the prophets.

Jews, Christians, and Muslims all understand themselves as Abraham’s (literal or spiritual) descendants. For all, Abraham is a paragon of faith and obedience.

Does this make Judaism, Christianity, and Islam “Abrahamic religions?” I have used that term without thinking about where it came from and what it signifies.

In Abrahamic Religions: On the Uses and Abuses of History, Aaron Hughes argues that the term “Abrahamic religions” is an ideological or theological construct — “a form of wish fulfillment and ecumenism” — that scholars of religion should set aside. Not only does the term have no historical meaning, Hughes alleges, but it obscures the way these three complex traditions “have historically intersected and thought with one another.”

As a historian, I sometimes find the enterprise of “Religious Studies” befuddling. My preference is to get on with the story rather than to spend very much time engaging categories and theory. Abrahamic Religions, however, provides a blunt reminder for anyone writing about religious traditions. Be careful!

Hughes makes his case very effectively. Until recently, when Jews, Christians, or Muslims, used the term “Abrahamic,” they did so not to describe the common ground shared by all, but to argue that they — and not the others — were Abraham’s true and only heirs. Then, over the course of the twentieth century, “Abrahamic religions” became a term connected with interfaith dialogue and a hope that the western monotheism could return to what Hughes describes as an imagined past of interfaith interaction and tolerance (symbolized by Muslim Spain, an imagined interfaith utopia). For many in the West, the term “Abrahamic religions” has replaced “Judeo-Christian” as a means of incorporating Muslims within a framework of mutual respect.

While many contemporaries no doubt prefer this ideology or theology to the supersessionist Christian and Muslim claims that preceded it and to fears of an unending “clash of civilizations,” it is still an ideologically loaded “theological invention.” Furthermore, the term seeks to project a set of vague but positive essential traits onto these three traditions, instead of grappling with them in their enormous diversity (and obvious mixtures of admirable and nefarious impulses). Hughes is not saying that these three traditions have no similarities or points of contact. Instead, his argument is that the term “Abrahamic religions” obscures and distorts far more than it illumines their intertwined histories.

This is a smart and convincing book. “Scholars of religion,” Hughes insists, “have to avoid employing words that we think adequately analyze or theorize our data without asking where the words themselves came from.” It’s a good caution, and I will proceed with greater caution in future semesters.

One caveat and one sidebar, neither of which interferes with my appreciation of Hughes’s main argument. First, Hughes takes a needlessly minimalistic approach toward the historicity of scripture. He introduces Abraham as an “ahistorical” figure and flatly states that “we have no evidence for the existence of Abraham or his progeny.” Well, I wouldn’t say no evidence, because the Abraham material in Genesis is obviously evidence of a sort. It might be poor evidence for a historical Abraham, but it’s something rather than nothing. Abraham is a mythical figure, but that does not exclude a historical Abraham.

Second, in the tradition of Jonathan Z. Smith, Hughes more broadly asserts that religions (and of course he questions the unthinking use of the term “religion”) “are not reified essences. They are, on the contrary, large canopies under which coexist manifold, complex, and often contradictory elements.” I also find this a useful reminder. As evidence, Hughes points to the development of Islam during as following Muhammad’s lifetime. He suggests that it is entirely unclear when Muhammad’s early followers understood themselves to be practicing “Islam,” something entirely distinct from the monotheistic message of the Jewish-Arab tribes Muhammad encountered in Yathrib. For some time, the boundaries between what became “Islam” and what are still very uncertain forms of Arabian Christianity and Judaism were porous. Only later did those lines harden. “We thus need to move beyond words, categories, and models,” Hughes concludes, “which imply three discrete religious traditions … with a shared essence that interact with each other.”

Sigh. More work.