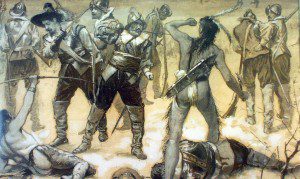

In 1637, English forces and their native allies encircled a Pequot village and burned alive some five hundred men, women, and children. John Mason termed it a “fiery oven” and declared: “It was the LORDS DOINGS, and it is marvelous to our Eyes.” William Bradford, then governor of New Plymouth, allowed that “it was a fearful sight to see them thus frying in the fire.” The stench was horrendous. Bradford, though, declared that “the victory seemed a sweet sacrifice.” Why did early New Englanders describe the massacre as a sacrifice that pleased the Lord?

In 1774, John Adams wandered into St. Mary’s Catholic Church in Philadelphia and described the “awfull” mass in a letter to his wife Abigail:

Here is every Thing which can lay hold of the Eye, Ear, and Imagination. Every Thing which can charm and bewitch the simple and Ignorant. I wonder how Luther ever broke the spell.

Centuries after the Reformation-era iconoclasm that destroyed religious objects in Zurich, England, and elsewhere (and which Luther himself condemned, believing the destruction of objects would end with the killing of people), why was John Adams so horrified by beads, holy water, and a richly decorated altar? And why, at the same time, did someone like Adams take up only the pen against such objects?

Many British colonies in North America made blasphemy a capital crime. When John Cotton proposed that twenty-four crimes be capital offenses in 1636, he placed blasphemy on the top of his list. With the elevation of the “word” to a position of utmost importance, Protestants worried greatly about blasphemy, slander, and unruly tongues more generally. Although a good number of individuals were brought before colonial courts and charged with blasphemy, magistrates and judges generally avoided imposing the penalty of death. Lesser punishments, though, were sometimes harsh. John Rogers, a Baptist in New Haven, was charged with blasphemy for “reproaching the Ministers.” He had to sit on the gallows with a halter around his neck, then was whipped on two separate occasions, spent six weeks “chained to the sill” in prison, then spent three more years in prison. Why was it a case of “blasphemy” rather than “heresy?”

In her Sacred Violence in Early America, Susan Juster demonstrates that such questions are best answered when placed within the context of medieval sensibilities, the Reformation, and ongoing religious warfare in Europe. It’s a book both sobering and “marvelous,” sobering for the sheer quantity of religion-inflected and -inspired violence in early America but marvelous for its rich mining of sources and ability to shed new light on them.

In her Sacred Violence in Early America, Susan Juster demonstrates that such questions are best answered when placed within the context of medieval sensibilities, the Reformation, and ongoing religious warfare in Europe. It’s a book both sobering and “marvelous,” sobering for the sheer quantity of religion-inflected and -inspired violence in early America but marvelous for its rich mining of sources and ability to shed new light on them.

It’s also a book full of ironies. Calvin, Zwingli, and many American Protestants considered the Catholic Eucharist “pagan barbarism masquerading as Christian doctrine,” a relic of blood sacrifice with which Christ’s sacrifice had rightly done away. Yet those same Protestants rejoiced as the blood of natives appeased God’s wrath, wrath kindled by the sins of natives and settlers alike.

Protestants largely believed that the era of “holy war” had ended, superseded by “just war” more limited and regulated. Yet at the same time, English settlers invoked Old Testament narratives such as that of Saul and the Amalekites to argue that their enemies merited complete annihilation.

Juster’s discussion of idolatry and iconoclasm is especially keen. “For Protestants,” she states, “idolatry was the ur-sin, the transgression that encompassed all the other sins the Reformation had sought to eradicate. Atavistic notions of blood sacrifice, of transubstantiated hosts, of crusades, of malediction — all were symptoms, or manifestations, of idolatry: of venerating a human invention (the sacrificial scapegoat, bloodlust, verbal power) over God.” Since anything could become an idol, danger lurked everywhere, even (as Catherine Brekus has demonstrated in her portrait of Sarah Osborn) in one’s love for one’s children or spouse.

But of course, an attachment to religious objects proved impossible to eradicate fully. Ornate furnishings gradually crept back into many churches. Protestants treasured books, especially the Bible. Protestants whose ancestors had criticized Catholics for creating relics out of saints’ bodies, pilfered hair, clothing, and other relics from the tombs of heroes such as George Whitefield (as Mormons would do with Joseph Smith’s hair and coffin in the nineteenth century).

What I find most valuable in Juster’s book is her long view. In each of her four chapters (“Blood Sacrifice,” “Holy War,” “Malediction,” and “Iconoclasm,” she carefully lays out the medieval, Reformation, and colonial (Spanish and English, at least) context of her themes. She pays particularly close attention to the English Civil War, an important backdrop for events in New England, Maryland, and Virginia. Juster’s analysis makes a strong argument that early American religious history can only be understood not only in an “Atlantic world” context but in the context of Christian conflict and debates that predate the Reformation and still resonated strongly at the time of the American Revolution.