[You can also read previous posts in the series]

Imagine a world where families operate like corporations. Parents are management, but efficiency and profitably determine all aspects of family life. Children are both assets and employees; resources are allocated according to potential. And if things don’t work out with a troublesome teen or toddler? Well, you can send them packing, no harm, no foul. Children too can move to another family or negotiate with their parents for bedroom upgrades, extended curfews, and increased allowance.

That disconcerted feeling you have right now? It’s probably similar to what an antebellum Protestant would experience encountering corporate evangelicalism. Never mind whether market-driven families are good or bad, it simply feels unnatural, right? Yet most evangelicals don’t think twice about “church shopping” based on programs, amenities, and “personal fit,” or devoting substantial portions of church budgets to the praise and worship industrial complex, or farming out the development of Vacation Bible School curriculum to an unknown corporation, or discarding a denominational affiliation like last year’s skinny jeans. It’s just what you do.

There is nothing intrinsically natural or unnatural about corporate evangelicalism. Religion is no less immune to business influence than family is to science, or business itself is to family. But such borrowings are not inevitable either. Some stick, others never take. They are, in other words, historically contingent, and as such they beg for an explanation.

Really we are tackling two questions this time. First, when did (at least some) evangelicals become “respectable?” And then when and how did middle-class Protestants start applying the rules and assumptions of the marketplace to the sanctuary?

Let’s begin with the birth of respectable evangelicalism in the 1830s. Upwardly-mobile evangelicals, like the Methodist author Phoebe Palmer, reoriented their inherited faith to accommodate their new social circumstances. Many of these pioneers were women and they effectively domesticated the “personal relationship with God” to comport to the domestic sphere, swapping the howl of the frontier camp meeting for a quiet conversation in the parlor.

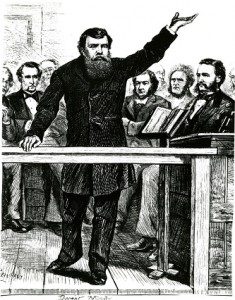

An evangelical orientation that abided by the standards of middle-class propriety soon spread across denominations. It reached not only women, but also the husbands, sons, and brothers who inhabited the male-centric world of middle-class business. The lawyer-turned-revivalist Charles Finney also made inroads among the business classes with the message that salvation was a choice.

But none of this changed the middle-class conviction that faith and market operated by different rules. Nor did it change respectable suspicions of the market. “The whole credit system, if not absolutely sinful, is nevertheless so highly dangerous that no Christian should embark on it,” Finney warned. And no respectable Protestant before the Civil War would have suggested that religious institutions operate on commercial principles.

The distinction between faith and market began to change amid a financial panic in 1857. As stocks plummeted and banks collapsed, evangelical businessmen dropped to their knees at noontime prayer meetings. They were conducted in downtown auditoriums and purportedly led by, and for, businessmen. (Read Kathryn Long’s fantastic book to learn more about how women’s participation in these revivals was erased.) The success of this “businessman’s revival” encouraged the co-mingling of business and religious identities. It also subtly shifted the focus of evangelical participants to the wider public world.

When the Civil War broke out a few years later, many of these same evangelical businessmen organized material and spiritual support for the Union Army. In the 1870s and after, they turned their attention to northern cities. They organized relief after the Great Chicago Fire, for example, tackled urban vices like prostitution, fought government corruption, and provided social services through organizations like the YMCA. There is plenty to criticize in these efforts (ask your nearest labor historian), but they led many a middle-class Protestant to think of business as a source of social virtue, not a threat.

The consummation of a market-based faith came through the Gilded Age ministry of the celebrity revivalist Dwight L. Moody. A successful, but uneducated, shoe salesman from Chicago, Moody exploded the old churchly Protestantism. His homespun preaching might have sounded like old-time religion, but it summarily displaced traditional understandings of self and salvation with business-inspired analogs.

Moody approached evangelization as a sales call. By his account, salvation was not found in a church community, or understood as a journey to the “celestial city.” It was a series of choices made by individuals. The most important of these was conversion. It was like becoming God’s junior partner; you entered into a direct personal relationship with God and were promised divine guidance and support.

This guidance came primarily through the Bible. It should be read “as if it were written for yourself,” Moody taught, like a businessman reading his daily correspondence. Where traditional Protestants saw theology as a safeguard to proper interpretation, Moody saw it as a barrier. One should simply read it “plainly” like a newspaper.

Moody’s business identity was key to his respectability. He presented himself a “man of business” and wore business suits rather than clerical robes. He also sat prominent businessmen on his platform whenever possible. The visages of Rockefeller, Dodge, and McCormick visually conveyed that his message had the blessing of the corporate establishment. Evangelical assumptions were smuggled into “respectable” Protestantism in business garb.

As Gilded Age industrial capitalism evolved into modern consumer capitalism, corporate evangelicalism transformed along with it. The new evangelicalism complemented the individualistic contract ideology embraced by professional opponents to unionization. It resonated with neoclassical economic assumptions about human behavior that began with the choices of “rational” individuals. And as white-collar work became routinized and goods more plentiful in the early twentieth century, it accommodated the practice of constructing personal identity through consumer choices. Acts of piety and acts of consumption became increasingly entwined in the minds of corporate evangelicals.

Moody’s associate and successor on the revival circuit, Reuben Torrey, was one of the many promoters of a consuming faith. He packed auditoriums around the world by treating the Bible like a divine catalog, listing goods and services available to any believer who met the associated requirements. Prayer, he taught, was the God-ordained way of getting things.

The new assumptions of corporate evangelicalism had cascading effects on traditional Protestantism. The belief that God would personally provide for material needs severed longstanding obligations between the wealthy and the poor. By the new accounting, God directly guided believers in how and where to give: perhaps to the poor, perhaps toward a new church gymnasium, or to a political action committee promoting family values. Anecdotes of divine promptings and last-minute unsolicited donations convinced many. It was charity structured by market relations: God’s “invisible hand” directing beneficence more efficiently than any charity or government could.

Corporate evangelicalism effectively transformed believers into economic actors. For anyone accepting the underlying logic, it only followed that these economic ideas were God-given “natural laws.” The market was transformed from an arena of moral danger into a divinely-engineered, self-correcting system. To challenge that system—whether by government regulation, labor unions, or socialism—was to challenge both the “American way” and God’s design.

Of course not everyone embraced economic individualism. The working classes put their faith in the power of solidarity and collective bargaining. Indeed, labor activists could argue for the “naturalness” of their approach with churchly precedents. Like traditional church discipline, might not unions also enact discipline over wayward workers for the greater good? Meanwhile social scientists, inspired by Darwin, postulated that nature and/or nurture were the primary drivers of human behavior, not individual choices. Humanity, like other species, should be studied as populations, not individuals.

Communal understandings of humanity helped spawn “modernist” Protestantism in the early twentieth century. Liberal theologians emphasized a social gospel over individual salvation. Sin was a matter of social structures, not choices. And salvation came by reform rather than a personal faith. God was the inanimate force of historical progress, and the Bible an ever-evolving record of that progress. It must be interpreted scientifically.

By the 1910s the battle lines were drawn. Socially-oriented liberals clustered in universities and the bureaucracies of mainline denominations. Free market fundamentalists poured their efforts into new parachurch institutions, consciously structured like corporations. Towering above its contemporaries was the Moody Bible Institute in Chicago (MBI). Though founded by Moody in the 1880s, it was transformed by the president and promotional guru of Quaker Oats, Henry Crowell, into a highly bureaucratized headquarters of corporate evangelism. Crowell also used branding strategies to undermine the religious authority of denominations, promoting Moody’s individualistic evangelicalism as “old-time religion,” free of liberal contamination.

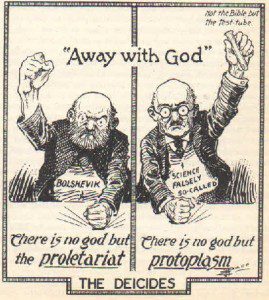

During this time, corporate evangelicals rallied a nationwide fundamentalist coalition against their modernist foes through a publication that purportedly outlined “The Fundamentals” of an interdenominational conservative Protestantism. They relentlessly attacked modernist theology, Darwinian science, and socialist economics as weakening church and state. With liberal theology seemingly discredited by World War I and then further gains during the Red Scare in 1919, they believed public opinion was on their side.

But, of course, such optimism was misguided. Liberals shrewdly formed coalitions with accommodating conservative and moderate denominationalists. Though the Federal Council of Churches they became the public face of American Protestantism. The fundamentalist movement, in contrast, sputtered in the mid-1920s, after which it was mercilessly mocked before being summarily ignored for the next thirty years.

This then is the creation story of corporate evangelicalism, but we should take care not to draw too stark a contrast with their liberal opponents. Liberal Protestants had their own forms of individualistic, capitalist-friendly, Protestantism, ably explained by Susan Curtis and Matthew Hedstrom. And some of the most prominent business leaders of the Progressive Era, John Rockefeller, for example, were allies of the liberal cause. Just as most judges do not treat their homes like a courtroom, no business person is compelled to understand their faith in economic terms. But some did, and corporate evangelicalism was one important manifestation of that impulse.

Thus, a new way of being an evangelical Protestant emerged in the 1910s, one that resonated with the times. Yet, the growth of corporate evangelicalism was sluggish until the last half of the century. Next month, I will explain this and look at some of the other varieties of evangelicalism that existed alongside it.