Today’s guest post comes from H. Paul Thompson, Jr., Dean of the College of Humanities and Professor of History at North Greenville University. His current research and writing interests focus on evangelical Christians, the Bible, and race and diversity, after his first book, A Most Stirring and Significant Episode: Religion and the Rise and Fall of Prohibition in Black Atlanta, 1865-1887, was published by Northern Illinois University Press in 2013. In this post he looks to a much more recent chapter in U.S. history.

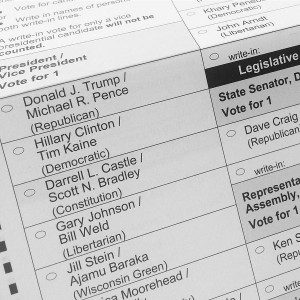

Donald Trump did not win an election on November 8, 2016.

He won 30 elections, out of 51.

Although there was one day set aside for American citizens to choose their next president, our states (and Washington, DC) hold separate elections; we do not have the “one national” election by which other republics and democracies choose their presidential equivalent. To think any differently about what happened in November leads to all kinds of ambiguities, distortions, and poorly informed analysis.

A primary source of the confusion on this matter is the cooperation between the polling industry and mainstream media. The media seem to prioritize reporting and analysis of polling data that emphasizes the percentage of voters claiming to support each of the main candidates, as though we elect our president by a direct vote of the people. Media personalities refer to “the election” or “the vote,” as though there was only one, direct, popular election. Talking heads then frequently disaggregated those percentages by assessing the interests and priorities of various demographic groups. Although this is an ongoing problem, in 2016 these practices distracted many from the real electoral story.

You may be thinking to yourself, “but I heard a lot of swing state commentary and analysis last year.” True, but I am arguing that speaking of “swing states” subtly and incorrectly implies the existence of a single national election in a way that speaking of, say, “Ohio’s presidential election,” would not. It may sound like an exceedingly fine point of distinction, but I think it is a meaningful one. Trump effectively focused his resources not so much on the aggregate number of voters in “swing states” as he did on the “presidential elections” in states such as Florida, Ohio, and Pennsylvania. Trump concluded his campaign in Michigan, and he and running mate were in Wisconsin twice as frequently as Hillary Clinton and Tim Kaine. Voters who live in states where Republicans regularly win presidential elections witnessed relatively few of Trump’s big campaign rallies.

When all was said and done, what actually occurred is that in addition to winning the presidential elections that Republican candidates normally win, Trump also won several presidential elections that Republican nominees rarely win, so he won enough electoral votes to become the nation’s 45th president. That is different — and more accurate — than saying he won “the” presidential election.

This is another way to say it: because Trump won presidential elections in Florida, Ohio, Michigan, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, Iowa, West Virginia, and North Carolina, he was able to add 119 electoral votes to those of the reliably Republican states and end up with 304 electoral votes (minus at least two unfaithful electors).

Any of the Republican primary candidates would have won the reliably red states, but those state elections alone don’t have enough electoral votes to elect a president. Because we do not directly elect our president, it was not “American voters” who elected Trump (as though a majority of American voters supported him). Trump simply won the right combination of state presidential elections. He knew what to do to win those elections. November’s elections strongly suggest that the majority of voters in reliably red and blue states will typically vote for any nominee of their respective parties, regardless of how questionable they may find him or her to be. They also suggest that regardless of what he does during his first term, Trump is unlikely to change the partisan basis for their presidential voting proclivities in 2020. Trump successfully figured out that becoming the U.S. president does not require appealing to the American people in some broad generic sense, rather it can be achieved by strategically appealing to a winning combination of state electorates.

When we misleadingly assert that Trump won “the” election, we are forced to explain “how” he won “the” election when Hilary Clinton won 48% of the popular vote to his 45.9%. Such imprecise wording also raises constitutionally uninformed questions about the “legitimacy” of Trump’s victory that could otherwise be avoided.

Correctly asserting that Trump won 30 state presidential elections enables us to see more clearly that the moral implications of voting or not voting, or of voting for a third-party candidate vary for Americans based on the state in which they live. In 2016, those who chose to vote for a third-party candidate (including many of my colleagues) were chided for “wasting” their vote, while those who declined to vote for any presidential candidate (including myself and many others) had to withstand charges of being irresponsible or arrogant. Our electoral college combined with the degree of a state’s political homogeneity must be considered when assessing such charges. I do not accept that they are true in some generic, or absolute sense. It is closer to the truth to say that declining to vote for Clinton in Michigan or Wisconsin “gave” those states to Trump than it is to say that declining to vote for Clinton “gave” South Carolina or North Dakota to Trump.

Correctly understanding our presidential election as multiple state elections also helps us understand the campaigning strategies of the major party candidates. If major party nominees expected to win by the popular vote, they would pour resources into get-out-the-vote efforts in all locations where supporters of their party are concentrated, rather than focus on swing state elections. A nominee’s visits to “safe” states would focus as much on get-out-the vote strategies as on fundraising, which they now stress.

While my analysis does not propose a path forward, I have attempted to provide an accurate foundation upon which to build such a path. As a Christian I feel compelled to search Holy Scripture for principles about how to relate to our secular government, and the most original and practical sermon I heard on this matter last year was titled “Sons of Liberty and Joy: How a Christian Relates to the State.” Preached by John Piper, I offer it as a starting point for a path forward for believers.