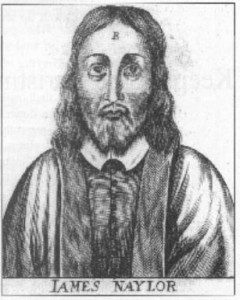

In October 1656, James Nayler rode into the English city of Bristol, accompanied by a small band of men and women who sang hosannas. Understood to have recreated Christ’s triumphal entry into Jerusalem, and accused of claiming to be Jesus Christ, Parliament convicted Nayler of “horrid blasphemy.”

Nayler was scourged with the whip, his flesh flayed and dirtied. His forehead was branded with a “B” for blasphemy, and his tongue was bored with a red-hot iron. A bare recitation of Nayler’s punishments cannot adequately convey their cruelty. The eyewitness accounts, both by his supporters and detractors, turn the stomach.

![mw42030[1]](https://wp-media.patheos.com/blogs/sites/168/2017/06/mw420301-235x300.jpg)

German etching of the “King of the Quakers,” 1657, courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery

What Damrosch does so effectively place Nayler’s ministry in its full religious and political context. First, he carefully traces the theological lines of division between the Quakers and their Puritan opponents. As is the case with so many of the ecclesiastical quarrels of seventeenth-century England, theirs was a conflict between groups that had much in common but also many disagreements. For example, many Puritans had supported lay prophesying (some separatists, such as John Robinson, extended this to women as well as men), as did the Quakers. The latter, however, marched into parish churches and exercised this gift by denouncing ministers.

Puritans retained a deep sense of their sinfulness, brooding about whether or not they truly belonged to Christ’s elect. Although anti-Puritans regarded them as incessantly self-righteous, Damrosch quips that Puritans actually had to act “viler than thou” because of their beliefs about human sinfulness. Quakers, by contrast, asserted that the literal indwelling of Christ in his elect produced actual holiness, if not perfection. The Friends pulled off the unlikely feat of making Puritans seem like libertines. They were deadly serious about avoiding mirth and laughter.

Damrosch also uses Nayler’s case to examine fissures within the Quaker movement itself. Nayler’s trip to Bristol and arrest came after his falling out with George Fox. Whereas Fox had worked with other itinerants such as Nayler as rough equals, by 1656 Fox increasingly sought to impose organizational discipline and his own authority on the Nayler also found himself in the middle of a related controversy between several women (including Martha Simmonds) and male Quaker leaders. Simmonds demanded that Nayler denounce her critics. Nayler refused to do so, but the in process suffered a breakdown. Nayler was beset by conflict on every side at the time of his arrest. As he sought to ward off organizational chaos (rather successfully) and anti-Quaker persecution (much less successfully), Fox used Nayler as a scapegoat in what amounted to a remaking of the Quaker movement in the years ahead. Quakerism shed much of the extravagance and outrageous public performances that characterized its confrontational first decade. Partly because Quakerism became rather different by century’s end from what it had been in the 1650s, Quaker historians for a very long time either ignored James Nayler or blunted his message.

Finally, Damrosch places these developments in the political and religious context of the Protectorate. The Parliament that tried Nayler in 1656 was a new creation, after Oliver Cromwell had dissolved its predecessor the year before. It was unclear on what basis this unicameral Parliament could or should try Nayler, and it was unclear whether or not Cromwell would back its harsh treatment of Nayler. Had Cromwell not sorely wanted funds for his campaigns against Spain, the Protector might have insisted on greater leniency for Nayler.

For anyone wanting a quick guide to why Quakers employed “thee” and “thou” and refused to remove their hats in court (but did remove them in church), Damrosch’s book is enormously useful. There are other excellent studies of the early Quaker movement (such as Barry Reay’s The Quakers and the English Civil Revolution), but none I have encountered are as lucid as Damrosch’s. He takes the theological arguments of the 1650s seriously and explicates them with great clarity.

The early Quakers are well worth our ongoing attention, for they raised a host of issues of ongoing concern and controversy among Protestants, such as the nature of biblical authority, the persistence or cessation of miracles, and the relationship between redeemed Christians, the Holy Spirit, and Jesus Christ.