Any would-be biographer of Charles Lindbergh needs to live up to the high standard set by her subject, who won the 1954 Pulitzer Prize for his inventive memoir of his historic 1927 flight from New York to Paris. Named for his famous plane, The Spirit of St. Louis benefited from the considerable editing assistance of Anne Morrow Lindbergh, whose Gift from the Sea replaced her husband’s work at the top of the bestseller list in 1955. (“To A.M.L.,” went his dedication, “Who will never realize how much of this book she has written.”)

“The book’s drama, unity, and sheer mastery of narrative form absolutely stunned,” wrote the Minnesota Historical Society’s Brian Horrigan of Spirit of St. Louis. “Here was the ‘Lindbergh Story,’ well known to anyone over a certain age, but now rendered with a vivacity and piercing kind of truth that was completely fresh.” Most famously, Lindbergh broke up the story of his 33+ hour flight with flashbacks, “rendered as thoughts and memories drifting through the pilot’s sleepy consciousness…. Mimicking the processes of memory itself, Lindbergh places these passages out of sequence, in bits and snatches, as images that suddenly emerge and quickly fade.” Reading SoSL has me wondering whether my “spiritual but not religious” biography of its author can take a less linear form…

“The book’s drama, unity, and sheer mastery of narrative form absolutely stunned,” wrote the Minnesota Historical Society’s Brian Horrigan of Spirit of St. Louis. “Here was the ‘Lindbergh Story,’ well known to anyone over a certain age, but now rendered with a vivacity and piercing kind of truth that was completely fresh.” Most famously, Lindbergh broke up the story of his 33+ hour flight with flashbacks, “rendered as thoughts and memories drifting through the pilot’s sleepy consciousness…. Mimicking the processes of memory itself, Lindbergh places these passages out of sequence, in bits and snatches, as images that suddenly emerge and quickly fade.” Reading SoSL has me wondering whether my “spiritual but not religious” biography of its author can take a less linear form…

But such choices are still two or three years in the distance. My most immediate interest is in the book’s frequent mentions of spirituality and religion, which had been entirely absent from Lindbergh’s first memoir, “We” (penned mere weeks after the 1927 flight, when Lindbergh decided to scrap his ghostwriter’s effort and take on the project himself). It’s not just that the author of The Spirit of St. Louis decided that “a pilot may drink the wine of the gods” or fretted that if he didn’t fly through a storm he “feel as though I’d been cheating… as though the evil spirits of the sky had disdained to sally forth in battle.” The cockpit becomes something like a monastic cell, the flight an ascetic challenge that leaves Lindbergh’s mind “divorced from my body, as though I were an awareness spreading out through space” and helps him recognize in himself “an element of spirit, a directive force that has stepped out from the background and taken control over both mind and body.”

More strikingly still, he revealed encounters with “ghostly presences” that began to enter his plane about twenty-two hours into the sleepless flight: “These phantoms speak with human voices… familiar voices, conversing and advising on my flight, discussing problems of my navigation, reassuring me, giving me messages of importance unattainable in ordinary life.”

“I’m on the border line of life,” Lindbergh remembered deciding at that point, “of life and a greater realm beyond… Is this death? Am I crossing the bridge which one sees only in last, departing moments?… Am I now more man or spirit?”

As a child, Lindbergh said he’d resented church (“an ordeal to be cautiously avoided”) and found God “vague and disturbing… as remote as the stars, and less real — you could see the stars on a clear night; but you never saw God…” But confronted with his own mortality hundreds of feet above the North Atlantic, the young adult had second thoughts:

It’s hard to be an agnostic up here in the Spirit of St. Louis, aware of the frailty of men’s devices, a part of the universe between its earth and stars. If one dies, all this goes on existing in a plan so perfectly balanced, so wonderfully simple, so incredibly complex that it’s far beyond our comprehension — worlds and moons revolving; planets orbiting on suns; suns flung with apparent recklessness through space. There’s the infinite magnitude of the universe; there’s the infinite detail of its matter — the outer star, the inner atom. And man conscious of it all — a worldly audience to what if not to God?

It’s passages like this that convinced me there’s a spiritual biography to be written. And I’m excited some day to dive into the SoSL manuscript collection at the Library of Congress, to see how the excerpts Lindbergh started drafting in the late 1930s reflected steps in his spiritual journey.

But for all his meditations about “the presence of another realm beyond,” SoSL is not a conversion story. God might have revealed himself personally to St. Antony and later ascetics; Lindbergh records no such encounter. The phantasms may have talked (“…but what did they tell me?,” he strains to recall as he finally reaches Ireland, “I can’t remember a single word they said”), but Lindbergh’s God remains silent and distant.

And not especially helpful. When Lindbergh finally lands in Paris, it’s because of human skill, knowledge, craftsmanship, and planning.

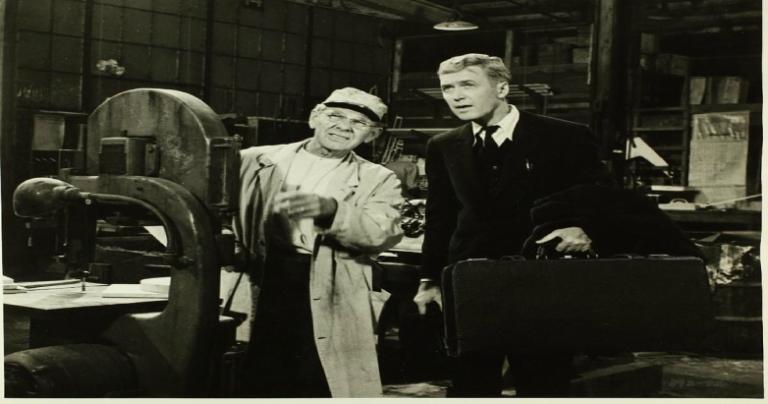

So it’s interesting to watch how God is inserted — however briefly — into the little-loved 1957 film version of Spirit of St. Louis by its writer-director: the great (and not terribly pious) Billy Wilder.

Early on, Wilder invents an exchange between Lindbergh and Frank Mahoney, president of the company that built Lindbergh’s iconic plane. Worried about carrying too much weight, the young Minnesotan decides not even to take a sextant.

“How are you going to navigate?”, asks Mahoney.

“Dead reckoning,” answers Lindbergh — played by a too-old Jimmy Stewart.

“What happens over the water?”

“Over the water, I keep watching the waves, see which direction the wind is blowing, allow for the drift…”

“…and hope the Lord will do the rest,” finishes Mahoney.

“No,” Lindbergh tells him. “I never bother the Lord. I’ll do the rest.”

Mahoney is astonished: “Might need a little help up there, don’t you think?”

“No, [he’d] only get in the way.”

Again, I think these are Wilder’s additions. But they do seem true to what Lindbergh says about his younger self. “It doesn’t matter whether you believe in God,” he remembered thinking as a child listening in on dinner table conversations about science. “Your experiment works, or it doesn’t.”

In a subsequent flashback, Wilder pulls out one of Lindbergh’s actual recollections: giving a flying lesson to a Catholic priest he had befriended in St. Louis, Father Hussman. “His handling of the controls was just as bad as I’d expected,” wrote Lindbergh, with typical candor. “But how he loved to fly!… And he wasn’t a fair-weather flyer. If it was windy or raining, he’d still go up with you if you’d take him, as though he wished to know God’s earth and air in all their phases.” At one point, they even dive down to wave hello from two hundred feet to a Catholic school.

So far, so true to the book. But then Wilder imagines a conversation between priest and pilot, following a rough landing:

“I guess I’m getting the hang of it,” says Hussman.

“No, Father, you’re not,” says his exasperated instructor. “And you never will.”

“Would you like to hear [my prayer] for landings?” asks the priest. “It’s out of the Psalms.”

“No thanks, Father,” mutters Lindbergh.

“Slim, don’t you ever pray?”

“Well, I don’t have to. I know how to land.”

“Let me ask you something,” Hussman presses on. “How come I never see you around the church? You don’t believe, hmm?”

“Yes, I believe,” replies Lindbergh. “I believe in an instrument panel, a pressure gauge, a compass, things I can see and touch. I can’t touch God.”

“You’re not supposed to. He touches you.”

Lindbergh furrows his brow: “Well now, tell me, Father: suppose you were up in this airplane all alone, and you stalled it. And you fell into a spin; you were dropping like a rock. You believe He would help me out of it?”

“I can’t say yes or no,” chuckles Father Hussman. “But He’d know I was falling.”

None of Lindbergh’s musings about mortality and the spiritual realm survived Wilder’s rewrite, and the filmmaker omits the “ghostly presences” who moved in and out of the Spirit of St. Louis. But Wilder does seize on one other religious detail from Lindbergh’s memoir in order to teach his protagonist a lesson in theology.

Reaching into his flying suit for a handkerchief about two-thirds of the way into the flight, Lindbergh finds a medal with the image of St. Christopher, patron saint of travelers. Unsure who put it there, he decides simply, “It was sent with me like a silent blessing or a prayer.”

But in Wilder’s telling, the medal was sent to Lindbergh by Father Hussman — and remains in Lindbergh’s sight as he nears the end of his journey, hanging prominently from his instruments.

As the movie ends, with an exhausted, disoriented Lindbergh approaching Le Bourget airfield, we hear the pilot trying to recall Hussman’s landing prayer. “Oh God,” he finally cries out, “help me.” Wilder cuts to a close-up of the saint’s medallion dangling in front of Lindbergh’s altimeter…

And the plane lands safely, to the cheers of tens of thousands. Almost in disbelief, Lindbergh looks at the medal.

I don’t know that Wilder’s additions belong in a Lindbergh biography. But they do suggest that in the middle of a Cold War against a Soviet civilization that Lindbergh himself decried for “godlessness,” it wasn’t enough to present an all-American hero who was spiritual, but not religious. Wilder’s Lindbergh had to learn what had just been added to dollar bills earlier that same year: “In God we trust.”

An earlier version of this post was published at The Pietist Schoolman.