We are joined today at the Anxious Bench by Kerry Pimblott, author of Faith in Black Power: Religion, Race, and Resistance in Cairo, Illinois, and Lecturer in International History at the University of Manchester.

Cairo, Ill., is on “life support.” At least that was the verdict of neurosurgeon and Secretary of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), Ben Carson, upon visiting the rural community earlier this summer. Carson’s grim diagnosis comes on the heels of HUD’s announcement in April that Cairo’s two public housing complexes – McBride and Elmwood Place – are unfit for human habitation and that their nearly 400 residents will be permanently relocated and the buildings razed.

The announcement stunned community members, not because the reports about the housing conditions were false (residents have been living with mold, vermin, lead contaminated water, electrical and plumbing problems for years) but because HUD’s decision was so final. The federal government will not build new public housing in the city. Adequate and affordable rental properties in the private sector are in short supply. Put simply, Cairo’s public housing residents are being told that they have few options but to uproot and leave the town they call home. If they do, Cairo – located in Alexander County, one of the nation’s fastest depopulating counties will lose a fifth of its population spelling disaster for the local school district and other vital public services.

On its face, the coming exodus could be viewed as a tragic but inevitable development for a declining river town. But, history offers a longer and more complex story of racial discrimination, disinvestment, and resistance that I tell in my recent book Faith in Black Power: Religion, Race, and Resistance in Cairo, Illinois (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2017).

* * *

The construction of Cairo’s two public housing complexes began during WWII following the passage of the 1937 U.S. Housing Act. Under FDR’s New Deal administrations, the federal government committed to clear urban slums and work with local authorities to develop improved public housing alternatives for American workers. As in many other cities, federal housing initiatives in Cairo conformed to prevailing patterns of racial segregation. Elmwood Place was designated for white residents and Pyramid Court (later renamed McBride) for African Americans.

Race was also a determining factor in site selection and the quality of property development. Elmwood Place would be built of brick and located uptown in a mixed income residential neighborhood on Elm Street between 37th and 40th Street. In contrast, the Pyramid Court consisted of cheaper wood-frame properties located downtown in a low-lying, flood prone site adjacent to the Mississippi River levee on Cedar between 12th and 15th Street.

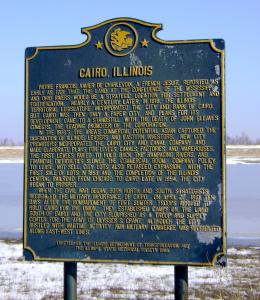

This story of Jim Crow public housing is one familiar to many American cities. What is less known, however, is that the Pyramid Court’s first residents in 1943 followed in the footsteps of an earlier generation of Black Cairoites. During the Civil War, Cairo served as the headquarters for the Union’s army and naval operations on the western front. After the Confiscation Acts of 1861 and 1862 and Lincoln’s subsequent Emancipation Proclamation, African Americans fled the cotton fields of the Deep South and crossed federal lines in growing numbers. Many were transported northwards on the Mississippi River aboard steamers to Cairo. Here, more than five thousand people were housed in the Union’s northernmost “contraband camp” located on 12th and Cedar Streets, the exact site of the contemporary McBride (formerly Pyramid Court) complex. Despite the proliferation of historical markers to Cairo’s Civil War history, none commemorate the city’s monumental significance to the thousands of formerly enslaved African Americans who took their first tentative steps toward freedom here.

Eyewitness accounts from abolitionists and missionaries paint a stark image of the conditions faced by refugees that lived in the camp during the war. These were unsanitary, disease-ridden, and overcrowded accommodations that the Quaker Levi Coffin described as granting “none of the comforts and few of the necessities of life.” After the war, most of the refugees would leave Cairo but a significant number remained, growing the city’s Black population from just 47 in 1860 to 1,849 in 1870.1 Those that stayed were responsible for laying the foundations of Cairo’s black community, building churches, fraternal orders, schools, unions, and businesses. In many cases, it was the direct descendants of this first generation of black Cairoites who carried their belongings into another federally sponsored housing initiative during WWII almost a century later.

* * *

The racial and spatial realities that shaped public housing in Cairo went unchanged even after HUD ordered an official end to segregation in 1966. In fact, the Alexander County Housing Authority (ACHA) developed a number of additional public housing complexes for the elderly with all but one operating on a segregated basis.2 As legal scholar Michael Seng notes, “Neither HUD nor the State of Illinois, whose laws also forbade segregated public housing, intervened.”3

Under the ACHA’s all-white leadership conditions in the Pyramid Court rapidly deteriorated. During a 1972 investigation by the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, HUD officials conceded that the housing project was in a “very sad condition” and in dire “need of modernization.” Pyramid Court residents testified to living in overcrowded dilapidated apartments infested by roaches and rats. When residents reported these problems to the housing authority often nothing was done. When repairs were made, residents were billed for the costs.4

By the late 1960s, the Pyramid Court emerged as a central flashpoint for black freedom struggles and its working class occupants as leaders of a potent citywide movement for racial change. At the forefront of this struggle was Reverend Charles Koen, a former Midwest Deputy Chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and Prime Minister of the St. Louis-based Black Liberators, who was born and raised in the Pyramid Courts. In 1969, Koen and other Cairo residents formed the United Front, filing lawsuits and launching an economic boycott aimed at promoting fair housing, nondiscriminatory hiring practices, and equal protection under the law. For the next three years, the Pyramid Court was subjected to near nightly assaults by law enforcement and white vigilantes seeking to intimidate residents into halting the boycott. In Faith in Black Power, I show how African American residents sustained their campaign in large part by building on the organizational and spiritual resources of the city’s black congregations. In turn, local Black Power leaders forged previously overlooked alliances with black church executives in some of the nation’s largest predominantly white denominations, resulting in the extension of legal and lobbying support as well as more than half-a-million dollars in financial aid to Cairo.

In October 1974, the United Front’s efforts culminated in a consent decree stipulating that all public housing be integrated, federal monies for renovations disbursed, and two black representatives appointed to the ACHA. Residents of the Pyramid Court formed a tenants rights union and negotiated a seat at the table as well as an affirmative action program for all janitorial and maintenance staff positions. When the ACHA recommended that fifty uninhabitable units in the Pyramid Court be demolished, tenants resisted and forced a compromise in which all but four of the buildings were remediated. In turn, United Front members launched their own housing initiative – the Egyptian Housing Development Corporation – and, despite considerable opposition from local officials, succeeded in building nearly 160 FHA-financed homes for low-income residents.5

* * *

In the decades since, battles have continued over conditions in the city’s public housing projects. In February 2016, HUD was forced to intervene and seized control of the local housing authority, citing a “years-long pattern of financial and operational mismanagement, poor housing conditions, and alleged civil rights violations against the households the housing authority was responsible for assisting.” In May, thirty residents of the Elmwood Place and McBride complexes filed suit against the ACHA for failing to maintain safe and sanitary properties. A settlement was reached earlier this summer by which time residents had already been encouraged to begin looking for alternative accommodations.

Some residents have already signed up for vouchers allowing them to secure affordable housing outside the city. Others have promised to resist relocation, forging a new grassroots organization called Men of Power, Women of Strength. The organization’s leader Steven Tarver favors the demolition of the complexes but only after new housing in the city is developed. If new homes are not provided, “we will fight,” he declared. “We will protest.”

- Figures and quotations taken from Kerry Pimblott, Faith in Black Power: Religion, Race, and Resistance in Cairo, Illinois (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2017), p. 30-33.

- US Commission on Civil Rights, Hearing before the United States Commission on Civil Rights (Cairo, Ill., March 23-25, 1972), p. 169-170.

- Michael P. Seng, “The Cairo Experience: Civil Rights Litigation in a Racial Powder Keg,” 61 Ore L Rev 285 (1982), p. 305.

- US Commission on Civil Rights, Hearing before the United States Commission on Civil Rights (Cairo, Ill., March 23-25, 1972), p. 161-168 and 206.

- Seng, 305-6; “Tenant Orgs To Be Formed,” The Monitor (East St. Louis, Ill.) May 13, 1971; “Tenant Group Seeks Meeting With Housing Board,” The Monitor (East St. Louis, Ill.) April 27, 1972.