Access Hollywood. Roy Moore. Stormy Daniels.

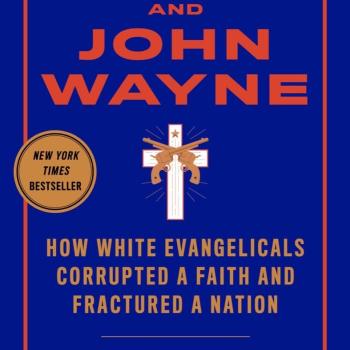

The cast of characters may shift from one scandal to the next, but evangelical Christians have remained remarkably consistent in their response to the sexual scandal du jour. Although evangelicals have not generally earned a reputation for tolerance, particularly when issues of sexual morality are involved, all that seems to have changed of late. These days evangelical Christians seem to be demonstrating an exceeding tolerance for sexual misconduct of all sorts–harassment, assault, the abuse of minors, extramarital sex, general vulgarity, and violence against women—at least when the alleged perpetrator is a Republican.

This tolerance has drawn attention from pollsters and evangelicals alike. A PRRI poll conducted in October, 2016—just after the release of the Access Hollywood tapes and just before the presidential election—revealed a startling sea change among evangelical Christians: Whereas five years earlier, only 30 percent of white evangelicals believed that “a person who commits an ‘immoral’ act could behave ethically in a public role,” that number had more than doubled to 72%. According to PRRI’s Robert P. Jones, “This dramatic abandonment of the whole idea of ‘value voters’ is one of the most stunning reversals in recent American political history.”

Some evangelical critics lamented this apparent embrace of moral relativism, most notably Russell Moore, president of the Ethics & Religious Liberty Commission of the Southern Baptist Convention. He took to Twitter to reiterate this concern in the wake of the Roy Moore (no relation) allegations: “Christian, if you cannot say definitively, no matter what, that adults creeping on teenage girls is wrong, do not tell me how you stand against moral relativism.”

But with the Stormy Daniels saga, evangelical apologists returned in full force. As Tony Perkins, head of the Family Research Council, explained so memorably, evangelical Christians were willing to give Trump “a mulligan”—“a do-over.”

So, a sitting president gets a pass for his alleged dalliances with a porn star, for committing adultery four months after his wife gave birth to their son, and for, purportedly arranging for the porn actress to receive hush money in the amount of $130,000.

What should one make of this?

Is this merely an example of the forgiveness Christians lavishly bestow upon those who trespass? A group of evangelical women who comprise part of the Trump’s base say just that. In an interview with CNN, this blond sextet of Trump enthusiasts effused over their “precious president,” the leader “God has ordained,” and explained that “Whenever anyone accepts Christ into their heart and life, and asks for forgiveness of their sins, and makes him Lord, everybody’s slate is wiped clean.”

So, do they care about his indiscretions with a porn star? They answer with a resounding “No!” Christianity, they explain, “is all about new beginnings, it’s all about starting over.” What happened in the past is irrelevant. “The whole concept is mercy and grace. That’s what Christianity is all about.” Perkins may have used the word “mulligan,” but the real word is grace: “We all have gotten a mulligan because of Christ Jesus,” they gush.

It’s worth pausing for a moment to note that evangelical Christians have been rather selective in how and when they dole out that forgiveness. Bill Clinton, for example, was not so fortunate. Nor, for that matter, was Hillary Clinton—for all her real and imagined offenses. Undocumented immigrants, African American men selling cigarettes, black boys playing with toy guns, LGBTQ folks, and a host of others have rarely been the recipients of extravagant grace on the part of evangelicals.

Nor does it come down to the question of who asks for forgiveness. Trump has made clear that he has never really found it necessary to ask for forgiveness, yet he has received it in large doses from evangelical Christians.

Is this a case of politics trumping religion? Or simply of abject hypocrisy? Or is there something more systemic involved?

Partisan politics do provide a fairly reliable predictor of evangelical outrage, but inconsistencies within the evangelical community go beyond that. Indeed, a careful examination of the way evangelicals have dealt with sexual abuse within their own communities suggests that more fundamental issues are at play. Because, of course, evangelical tolerance of sexual abuse isn’t new.

Evangelicalism has long been rife with instances of sexual abuse, minimizing, victim blaming, and cover-ups. From the highest levels of leadership to instances of misconduct at the local church, evangelicals have too often failed to identify abuse, to hold abusers accountable, and to prevent future instances of abuse. From the rampant abuse uncovered at Sovereign Grace Ministries and Bill Gothard’s IBLP, to John Piper’s advice to women to submit to abusive husbands, and to the resounding congregational affirmation of abusive pastor Andy Savage, the evangelical subcultural has a dismal record when it comes to calling out abusers and seeking justice for the abused.

In recent days a powerful voice has emerged from within the evangelical community, calling out Christians for their failure to confront sexual abuse within their own circles. Rachael Denhollander was the first victim to go public with her accusations against Larry Nassar, the sports doctor convicted of molesting dozens of young girls while affiliated with MSU athletics and USA Gymnastics. Denhollander’s victim impact statement is devastating, and demands a close read, in its entirety.

A conservative Christian herself, Denhollander directly addresses Nassar’s pleas for forgiveness:

“You spoke of praying for forgiveness. But Larry, if you have read the Bible you carry, you know forgiveness does not come from doing good things, as if good deeds can erase what you have done. It comes from repentance which requires facing and acknowledging the truth about what you have done in all of its utter depravity and horror without mitigation, without excuse, without acting as if good deeds can erase what you have seen this courtroom today….

The Bible you speak carries a final judgment where all of God’s wrath and eternal terror is poured out on men like you. Should you ever reach the point of truly facing what you have done, the guilt will be crushing. And that is what makes the gospel of Christ so sweet. Because it extends grace and hope and mercy where none should be found. And it will be there for you.

I pray you experience the soul crushing weight of guilt so you may someday experience true repentance and true forgiveness from God, which you need far more than forgiveness from me — though I extend that to you as well.”

Denhollander’s courageous and unsparing statement went viral, and for good reason. But she followed up her statement with an interview with Christianity Today, where she noted how it was interesting “that every single Christian publication or speaker that has mentioned my statement has only ever focused on the aspect of forgiveness. Very few, if any of them, have recognized what else came with that statement, which was a swift and intentional pursuit of God’s justice. Both of those are biblical concepts. Both of those represent Christ. We do not do well when we focus on only one of them.”

Denhollander spoke further on the failure of the evangelical church to support abuse victims. “Church is one of the least safe places to acknowledge abuse because the way it is counseled is, more often than not, damaging to the victim. There is an abhorrent lack of knowledge for the damage and devastation that sexual assault brings. It is with deep regret that I say the church is one of the worst places to go for help. That’s a hard thing to say, because I am a very conservative evangelical, but that is the truth. There are very, very few who have ever found true help in the church.”

In assessing the evangelical response to sexual abuse, Denhollander draws a clear distinction between how evangelicals condemn abuse when it happens outside their fold, but seem unable, or unwilling, to do the same when it occurs among their own. Denhollander sought to use her expertise to advocate for victims of evangelical pastor C.J. Mahaney and the Sovereign Grace Ministries, but she found herself stymied. Evangelical leaders sought to discredit her, and she was told by elders of her church that she needed to find a new church, “it wasn’t the place for us.”

All of this left Denhollander to conclude that “It’s very obvious that they are not going to speak out against sexual assault when it’s in their own community.”

“So that leaves me with the question,” Denhollander adds: “What happens when it’s a trusted person at this church? What happens when it’s a trusted person in these other evangelical organizations? The extent that one is willing to speak out against their own community is the bright line test for how much they care and how much they understand.”

“We have failed abhorrently as Christians when it comes to that test. We are very happy to use sexual assault as a convenient whipping block when it’s outside our community. When the Penn State scandal broke, prominent evangelical leaders were very, very quick to call for accountability, to call for change. But when it was within our own community, the immediate response was to vilify the victims or to say things that were at times blatantly and demonstratively untrue about the organization and the leader of the organization. There was a complete refusal to engage with the evidence. It did not even matter”.

Although she has found herself heralded as a hero by evangelicals in light of the Nassar case, she suggests that, had her abuser been a Sovereign Grace Ministries pastor instead of an MSU gymnastics coach, “I would not only not have evangelical support, I would be actively vilified and lied about by every single evangelical leader out there. The only reason I am able to have the support of these leaders now is because I am speaking out against an organization not within their community. Had I been so unfortunate so as to have been victimized by someone in their community, someone in the Sovereign Grace network, I would not only not have their support, I would be massively shunned. That’s the reality.”

This testimony ought to give all Christians pause.

What sort of theology supports these structures of hypocrisy, injustice, and abuse? What sort of religious culture perpetuates and condones abuse, disempowers victims, and at what cost?

“The gospel of Jesus Christ does not need your protection,” Denhollander concludes. “It defies the gospel of Christ when we do not call out abuse and enable abuse in our own church. Jesus Christ does not need your protection; he needs your obedience. Obedience means that you pursue justice and you stand up for the oppressed and you stand up for the victimized, and you tell the truth about the evil of sexual assault and the evil of covering it up.

Second, that obedience costs. It means that you will have to speak out against your own community. It will cost to stand up for the oppressed, and it should. If we’re not speaking out when it costs, then it doesn’t matter to us enough.”