Throughout U.S. history, “public charge” rules have been a powerful instrument of excluding immigrants on the basis of their poverty–and also on the basis of their religion, race, and ethnicity.

Last month, the Trump administration announced controversial plans to change the rules for 382,000 immigrants who use public assistance. Under these proposed changes, legal immigrants who lawfully use programs such as food assistance and Section 8 housing could be deemed a “public charge” and therefore denied a green card that would allow them to live and work in the United States. According to its proponents, the policy changes express the government’s commitment to financial responsibility. “Self-sufficiency has been a basic principle of United States immigration law since this country’s earliest immigration statutes,” states the proposal, and the new public charge rules are necessary to ensure that “the availability of public benefits not constitute an incentive for immigration to the United States.”

Public charge rules, on the surface, appear to express a commitment to government financial responsibility and individual self-sufficiency. However, a look at the origins and administration of public charge rules reveals that, throughout history, these rules have been about more than economic status. In fact, public charge rules have offered the U.S. government a flexible and powerful instrument for excluding people it has deemed undesirable, not only on because of their poverty, but also because of their religion, race, and ethnicity.

Excluding and Expelling the Poor

Restricting migration through public charge rules has deep roots in American history, as Hidetaka Hirota points out in his book Expelling the Poor: Atlantic Seaboard States and the Nineteenth-Century Origins of American Immigration Policy. American colonies as early as the seventeenth century relied on British poor law, which required parishes to provide for the local poor, and which also gave parishes the right to refuse aid to and remove paupers who did not reside in the parish. These laws laid the foundation for laws developed in states like New York and Massachusetts, where large numbers of immigrants arrived in the nineteenth century and where state governments, in response, developed laws that equipped them with “sweeping powers over foreigners.” In particular, states relied on laws that restricted the landing of aliens deemed “likely to become a public charge” and that gave officials great discretion in deciding the admissibility of immigrants

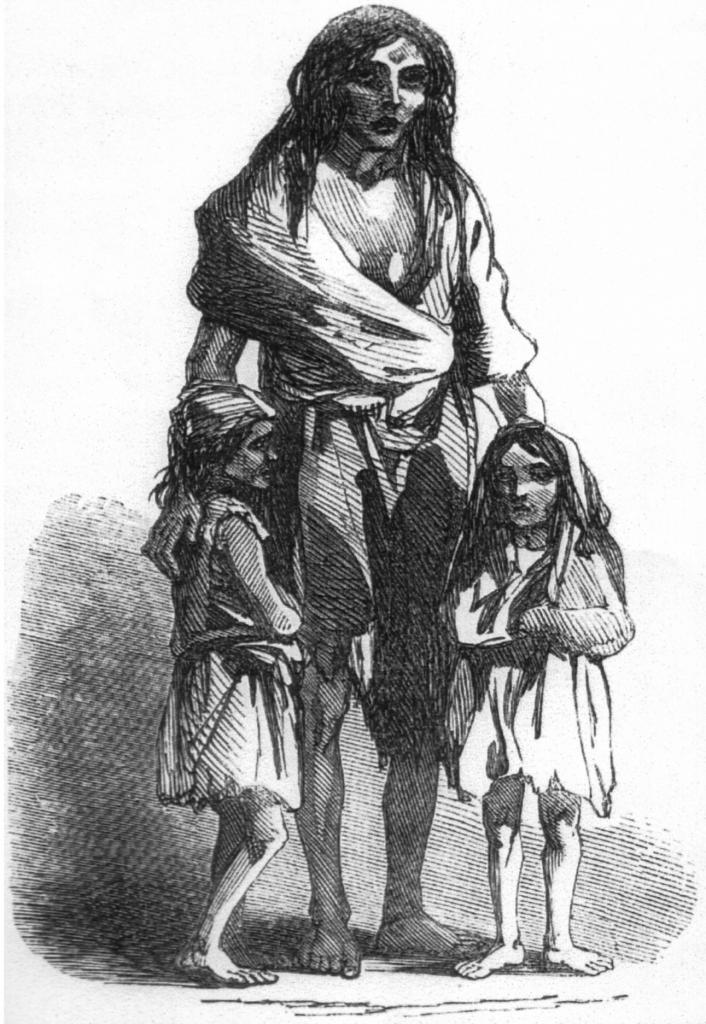

Massachusetts did not merely develop policies that restricted the entry of undesirable poor immigrants; it also created policies to remove them, often ruthlessly. Between 1830 and 1880, Massachusetts deported at least 50,000 immigrants who had fallen into poverty. Although these people had already become residents of the state, Massachusetts nonetheless sent these immigrants back to Ireland, Great Britain, Canada, and other states.

These state-level public charge rules had a long-lasting impact on American immigration law. Most notably, they served as the blueprint for federal-level public charge rules later in the nineteenth century. For example, the Immigration Act of 1882, the first federal immigration law that applied to all foreigners, banned the entrance of paupers, and it was modeled on laws that were developed in Massachusetts and New York.

Closing the Door to Impoverished Irish Catholics

In describing the origins of these public charge rules, Hirota explains that they were, in large part, a response to the influx of poor Irish immigrants during the antebellum period. Anti-Irish hostility during this period centered on the problem of Irish poverty, which was both a financial concern and an ideological one, as dependence on charity transgressed the nineteenth century belief that white individuals should be able to achieve economic independence through their own free labor. “Simply put, nativists resented many Irish immigrants’ lack of money to support themselves and the immigration policy they developed aimed to expel the indigent Irish dependent on public relief,” Hirota writes. In this way, he explains, “American immigration regulation emerged as a matter of class.”

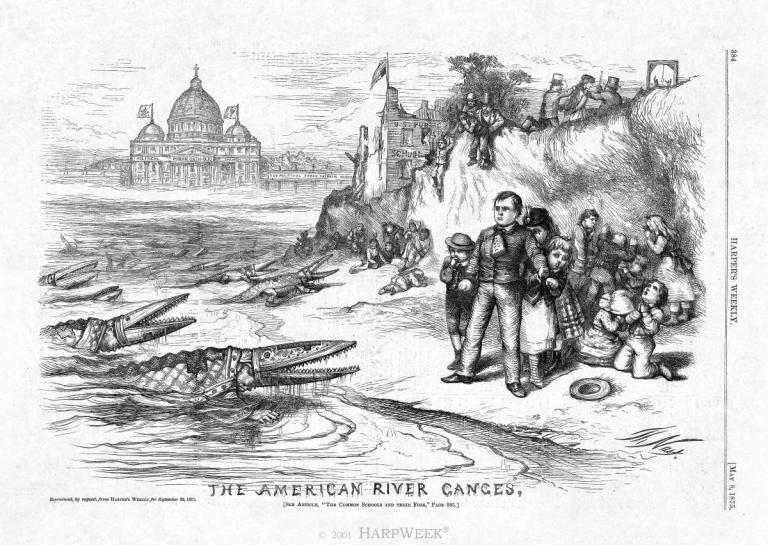

However, he points out that the Irish were also despised because they were Catholic. The Catholic population was about 35,000 in 1800, but by 1840, immigrants—especially Irish immigrants—increased the Catholic population to 663,000. Native-born Protestant Americans, especially those in historically Puritan states like Massachusetts, were deeply suspicious of Catholics, even outright hostile to them. As with their British predecessors, American Protestants viewed Catholics as inferior, superstitious, corrupt Christians whose loyalty to the Pope and the hierarchical Catholic Church made them particularly ill-suited to American democracy and freedom. This deep-seated prejudice gave rise to salacious anti-Catholic propaganda such as Maria Monk’s 1836 Awful Disclosures of the Hotel Dieu Nunnery of Montreal, as well as mob violence. In 1834, for example, a crowd of around fifty men in Charlestown, Massachusetts, burned an Ursuline convent to the ground, and bursts of anti-Catholic street violence erupted elsewhere in Boston and New York City.

Ultimately, public charge rules used the fact of Irish poverty as a reason to exclude and expel many Irish immigrants. However, it is also clear that the Irish were targeted not only because of their poverty, but also because of their religion. Public charge rules were, on their face, a form of economic exclusion, but in practice, they also functioned as a tool of religious exclusion.

Refusing Refuge to German Jews

Public charge rules functioned as a tool of religious exclusion again during the 1930s, when Jews hoping to escape Nazi Germany attempted to migrate to the United States. During this period, as would be the case during subsequent refugee crises in history, Americans strongly opposed accepting refugees. In July 1938, one public opinion poll published in Fortune found that only 4.9% of Americans surveyed believed that the United States should accept political refugees fleeing persecution in Europe. In an era of virulent anti-semitism, Americans appear to have been especially reluctant to accept Jewish refugees. In January 1939, in the wake of Kristallnacht, a Gallup poll found that 61% of survey respondents did not believe that the United States should open its doors 10,000 German refugee children, the vast majority of whom were Jewish.

American immigration officials were able to prevent refugees from entering the United States by relying on the immigration quotas established by the Johnson-Reed Act, but also by using an extremely stringent interpretation of public charge rules. As Stephen Porter points out in his book Benevolent Empire: Power, Humanitarianism, and the World’s Dispossessed, President Herbert Hoover in 1930 directed American consuls to apply public charge rules strictly, in response to American fears of labor competition during the Great Depression. The use of public charge rules ended up allowing the United States to admit far fewer immigrants than what was permitted under the Johnson-Reed quota limits, which were already set at unprecedentedly low levels. By restricting immigrants only to those who had wealth, the United States used less than 20% of its available immigration quotas, and immigration during this period dipped to its lowest level since the United States began keeping records in the 1830s. Importantly, the United States made no exceptions to admit refugees or asylum-seekers.

Anti-Semitic immigration officials were particularly harsh when applying the rules to Jewish applications for immigration. “Virtually all Jews applying to enter the United Staes to escape persecution abroad were required by the State Department Visa Division to have affidavits filed on their behalf by a sponsor in the United Staes promising to support the immigrant if granted admission,” Porter explains. “While other poor and potentially dependent immigrant applicants also had the affidavit requirement applied to them, contemporary refugee advocates and later observers have noted that it was applied much more strictly and systematically to the Jewish refugees, partially the result of strong pockets of anti-Semitism among American consuls abroad and their counterparts in Washington.”

Government policies in Nazi Germany impoverished Jews and made it even more difficult for them to clear the public charge hurdle and seek refuge in the United States. “By the time the Nuremberg laws had stripped all German Jews of their citizenship in September 1935—and thus what little actually remained of their civil rights—most had already been robbed of the means to earn a sustainable livelihood,” writes Porter. “Making matters worse, the German government progressively limited the amount of capital and valuables with which emigrants were allowed to leave. By 1937 the level had dwindled to 10 Deutschmarks, equaling about $4 U.S.” In other words, German policies reduced Jews to poverty, and American policies refused Germany Jews due to their poverty.

As these examples show, policies matter, but so do practices of implementation. Indeed, it is often in the realm of administration that the discriminatory power of public charge rules has been most salient. Historically, public charge rules have functioned as convenient vehicles for bias because they have been extraordinarily flexible in their interpretation and application.

Public charge rules further benefit from being wrapped in the alluring language of financial self-sufficiency. Today, open discrimination on the basis of religion and race might not appeal to most Americans, but the value of economic responsibility certainly does. But the truth is that throughout history, racial and religious antagonism has shaped the creation and application of public charge rules as much as economic concerns have. Americans considering the Trump administration’s newest immigration policy changes would do well to learn from the past and consider that the current proposal might have causes and consequences that reach far beyond face-value commitment to financial independence.