The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned . . . .

by William Butler Yeats,

from The Second Coming

A tide of small bodies riddled with bullets stopped our world, arrested our attention, and held us, for a week, in a reality we cannot bear: that this is the world we live in, this is really who we are.

Shooter, victims, murdered mother, shattered families, wounded town, madness making its way so easily past the mask of goodness we have constructed, and into the heart of our peace. All of it is part of who we are.

The next step, one we always take, begins our walk away from this reality, our walk into a delusion we think will be a way out: turning the story into good guys/bad guys, into a shoot-em-up/lock-em-up, in which we tell ourselves it isn’t us after all: it’s them. And we can control them.

Apocalyse the Experience, which is what we have just been through, is never the end of everything, but always the end of something very precious. It is an event that we cannot forget. The world, in our knowing of it, moves devastatingly from utopian to dystopian. Survivors wander through the wreckage. Time ends. The hours no longer can be counted in the same way. New time begins.

This is the truth about apocalypse, which is the setting for Advent, in the readings assigned for the entire season. Then as now, the change is not predictable by any calendar. It has no vestige of a beginning and no prospect of an end. But it has played out for centuries, in the Holocaust, in pogroms, in caste, race and religion wars in every region and nation, in witch hunts; in My Lai, in Afghanistan, in Hiroshima and the Gaza.

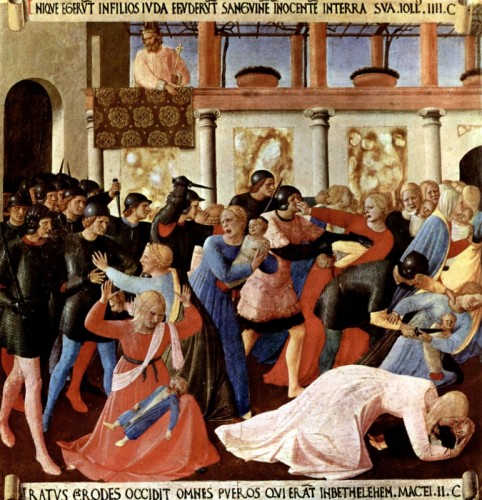

The Slaughter of the Innocents is a part of the story of Bethlehem, and the birth of Christ. These killings, into which Jesus is born, are akin to the Newtown school shootings — very young children, birth to age 2, are killed, and by military assault weapons, in fact, by soldiers who burst in like madmen. This tale is akin to all the massacres we have borne these past decades: Columbine, the Aurora Colorado movie theatre, Virginia Tech, the mall shooting, the neo-Nazi at the Capitol, the psychiatrist at Fort Hood. The aftermath is terrible.

The Slaughter of the Innocents is a part of the story of Bethlehem, and the birth of Christ. These killings, into which Jesus is born, are akin to the Newtown school shootings — very young children, birth to age 2, are killed, and by military assault weapons, in fact, by soldiers who burst in like madmen. This tale is akin to all the massacres we have borne these past decades: Columbine, the Aurora Colorado movie theatre, Virginia Tech, the mall shooting, the neo-Nazi at the Capitol, the psychiatrist at Fort Hood. The aftermath is terrible.

These killings happen in Bethlehem. And they happen here and now, in Newtown. And they have happened in every age. Madness, mayhem, paranoia, zero sum thinking: these are part of our humanness. But they are not all that we are.

Here is Matthews’s tale (2: 13-23):

An angel of the Lord appeared to Joseph in a dream and said, “Get up, take the child and his mother, and flee to Egypt, and remain there until I tell you; for Herod is about to search for the child, to destroy him.” Then Joseph got up, took the child and his mother by night and fled. Herod . . . . infuriated, sent and killed all the children in and around Bethlehem who were two years old or under. Then was fulfilled what had been spoken through the prophet Jeremiah: “A voice was heard in Ramah, wailing and loud lamentation, Rachel weeping for her children; she refused to be consoled, because they are no more.”

The story tells us that the Christ child was born into bedlam, mayhem, the madness which is our world. The Child was born because, pervasive as this reality about us is, it is not all we are. The story was written to give us hope.

The story tells us that the Christ child was born into bedlam, mayhem, the madness which is our world. The Child was born because, pervasive as this reality about us is, it is not all we are. The story was written to give us hope.

The story tells us that our salvation is born in the midst of such times, into the heart of our darkness, in a moment when time is shattered and new time begins.

And our salvation is brought to us by a survivor of the worst that can befall, by a child whose light was not extinguished, a child who understands deeply what has happened, a child who remembers, a child who was not killed. This is the Child who grows in wisdom and stature, who amazes the rabbis in the temple, who has a perspective unlike anyone’s.

The story tells us that the people of Bethlehem were barely aware of this Child. Devastated by the slaughter, picking up their splintered lives, their broken hearts, their stabbing fears, their traumatized surviving children, they also found among the wreckage the words that promise the Messiah will be born to them, especially to them. They carried this promise, in tears, as they buried their dead children.

The story tells us that God does not abandon us to face our peril alone. That God drew Mary and Joseph to this place and this time for this birth. We tend to think the slaughter was later, after the birth and after the flight, but it is possible that the time frame here is very short, that the star brought the kings to the moment of birth, that Herod’s angry order was given impatiently early, that the rumors of murder were rife in the streets as Mary lay down in the straw. It is possible that the carnage was beginning even as she gave birth. And so it is possible to say that she gave birth among the slaughtered.

The hope of our time lives among survivors. We cannot outrun, outgun, or outwit what is monstrous in this world. But in facing the truth of our reality, we can see light in its darkness, and hear angels singing there, for it is into this reality that Christmas comes.

The hope of our time lives among survivors. We cannot outrun, outgun, or outwit what is monstrous in this world. But in facing the truth of our reality, we can see light in its darkness, and hear angels singing there, for it is into this reality that Christmas comes.

May we remember that Christmas comes to meet our desperate need. God with us is the theme.

Never we know but in sleet and in snow,

The place where the great fires are,

That the midst of the earth is a raging mirth

And the heart of the earth a star.

And at night we win to the ancient inn

Where the child in the frost is furled,

We follow the feet where all souls meet

At the inn at the end of the world.

The gods lie dead where the leaves lie red,

For the flame of the sun is flown,

The gods lie cold where the leaves lie gold,

And a Child comes forth alone.

– G.K. Chesterton, from A Child of the Snows

________________________________________________

Illustrations:

1.Mary with the Infant Jesus. by Andrea Mantegna. 1455. Gemäldegalerie (Berlin, Germany). Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.

2. Massacre of the Innocents in Bethlehem. Fra Angelico. 1450. Florence, Italy. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.

3. Slaughter of the Innocents, detail. Reni, Guido. 1611-12. Pinacoteca nazionale (Bologna, Italy) Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.

4. Birth of Christ, detail. 1545-48. La Tour, Georges du Mesnil de. Le Petit Palais, Paris, France. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.