David Russell Mosley

Ordinary Time

8 October 2014

The Edge of Elfland

Hudson, New Hampshire

Dear Friends and Family,

That Hideous Strength is perhaps often viewed as one of the strangest and weakest of Lewis’s fictional books. It certainly makes little sense if we think of it as the culmination of a Space Trilogy since the entire book takes place on Earth. What’s more this book makes a sudden introduction of Arthurian mythology that is completely absent from the previous two. Some even criticise it for its portrayal of gender and male-female relationships (This however, is contested by Alison Milbank who seems to think Lewis get this more right than wrong. I don’t have a source for this as it is something she said in her class on Fantasy and Religion). And yet, for all of this, I cannot help but love this book.

It helps that I am something of a sucker for all things Arthurian. As evidenced by these posts. But even beyond this, Lewis does something very interesting on a cosmic level in this book. The book sets the tale of two protagonists, Jane Studdock and her husband Mark. Jane and Mark are still newly married, both academics, though she has put her work to the side for the time beings, finding it hard to return to it (she’s doing a PhD on Donne). Jane is troubled by dreams she’s having. She later finds out that she is a seer, that is, sometimes she dreams things that are currently happening. It’s important to note two things, first, Jane does not dream or predict the future. She is simply capable of dreaming the present. Second, Jane does not do this by calling upon spirits of any kind. It is, rather, hereditary. And it is this point that I find most interesting. Lewis has constructed a world where a human creature can, while asleep, ‘dream things true’ as Shakespeare wrote in Romeo and Juliet. In some ways, this is the epitome of an enchanted cosmos. Jane sees the present, and even more, she sees the present in a way that is useful to the Christians she eventually fully joins at the St Anne’s Manor. Lewis doesn’t make it obvious that these are visions given to Jane by God in say the way Daniel, Paul, John, or others have had visions. She isn’t seeing heavenly realities, but what she sees becomes guided by the influence the Director has over her. She is an enchanted human being, with a native ability that is intended for good uses, but can be turned to evil.

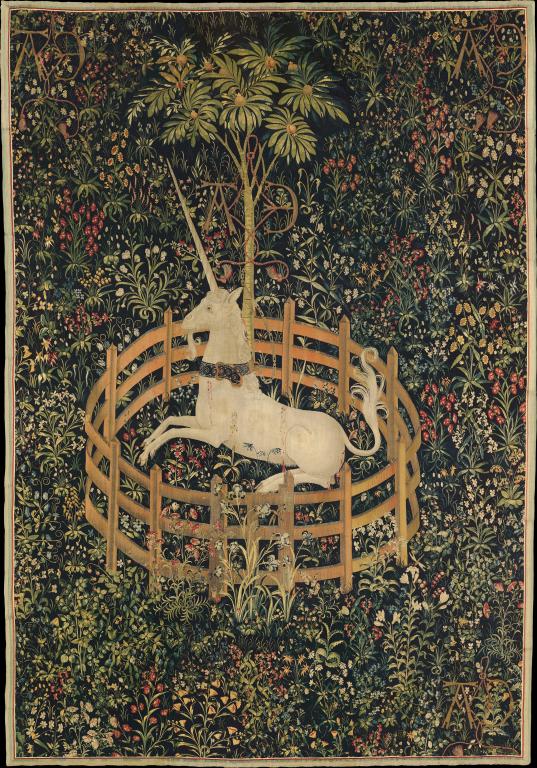

However, the enchantment runs even deeper than this. When Merlin is awakened or brought back into time, what his state was before his reanimation is uncertain, he is ravenous to reconnect with the rocks, fields, and trees around him. But he isn’t allowed to. The Director, the current Pendragon, will not allow him, it is no longer, according to God it would seem, acceptable. Nevertheless, the Director himself has the ability to tame animals in a way no other human can. Mice come at his beck and call to clean up crumbs; a bear lives with them (along with a few other animals); they have a garden, which doesn’t seem to have any particularly enchanted properties to it (not like the animals do), but living within nature does seem to be an integral aspect of their lives at St Anne’s. In fact, the garden growing, animal raising people of St Anne’s are contrasted with the N.I.C.E. and their desire to denature the Earth.

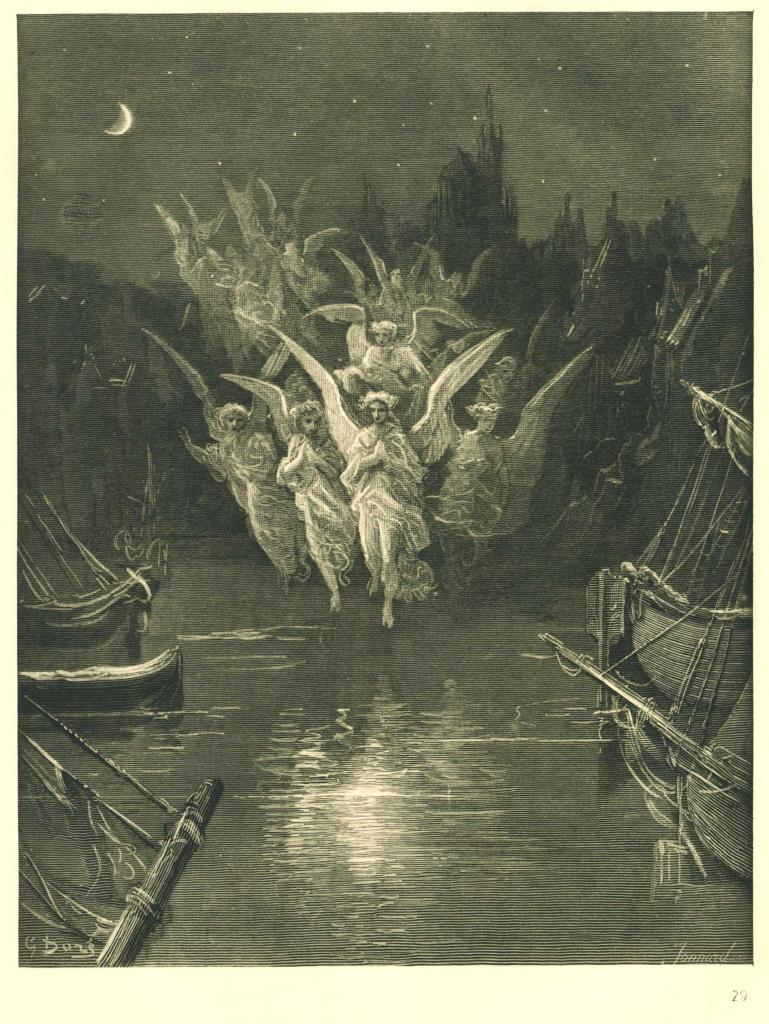

On the Angelic end of things, which has been the focus of the previous two letters in this series, there is decidedly less and more. Because the lens through which we see the world is the uninitiated Jane, rather than Ransom himself, encounters with the angelic are terrifying. There is a scene where Ivy, a member of the group at St Anne’s is reflecting on the Director’s encounters with angelic beings behind the planets (the wanderers) in the cosmos. ‘“Do you know,” said Ivy in a low voice, “that’s a thing I don’t understand. They’re so eerie, those ones [angels] that come to visit you. I wouldn’t go near that part of the house if I thought anything was there, not if you paid me a hundred pounds. But I don’t feel like that about God. But he ought to be worse, if you see what I mean.” “He was, once,” said the Director. “You are quite right about the powers. Angels in general are not good company for men in general, even when they are good angels and good men. It’s all in St. Paul. But as for Maledil Himself, all that changed: it was changed by what happened at Bethlehem.”’ Lewis does something I can’t quite fully account for here. Throughout the series, he has somewhat acted as though Earth, Thulcandra, the Silent Planet were purely under the sway of Satan and that the other Oyarsa cannot enter it, and that its own eldila are not always on our side (even if they aren’t always against us). This makes little sense when compared with Scripture where throughout the Old Testament and Apocrypha angels not only appear but aid humanity in obvious ways. In the New Testament, they fade somewhat behind the glory of Christ, but are still present. Perhaps, however, what Lewis is doing here is distinguishing between the hierarchies. Those great beings who guard and move the planets cannot enter into ours easily and are bad company for us, but those who are intended to work directly with us are not as bad company for us. Still, though, it is clear that we are meant to commune directly with God and not simply through the angels.

In the end, what That Hideous Strength gives us is the cosmic come home. The grand movements in the Fields of Arbol (Lewis’s “Old Solar” for the Cosmos) are affected by and affect what happens on Earth, not in an astrological way, but because the whole Cosmos, created and upheld by God, is also governed by his created beings and all of it is tending toward one end. It is all tending toward the overcoming of the world with the Kingdom of Heaven, of the overcoming of Britain with the kingdom of Logres. Let me leave you with the discussion of Logres in That Hideous Strength, keeping in mind that this discussion not only applies to every nation, but to the whole cosmos.

‘“It all began,” he [Dr Dimble] said, “when we discovered that the Arthurian story is mostly true history. There was a moment in the Sixth Century wen something that is always trying to break through into this country nearly succeeded. Logres was our name for it––it will do as well as another. And then … gradually we began to see all English history in a new way. We discovered the haunting.”

‘“What haunting?” asked Camilla.

‘“How something we may call Britain is always haunted by something we may call Logres. Haven’t you noticed that we are two countries? After every Arthur, a Mordred; behind ever Milton, a Cromwell: a nation of poets, a nation of shopkeepers: the home of Sidney––and of Cecil Rhodes. Is it any wonder they call us hypocrites? But what they mistake for hypocrisy is really the struggle between Logres and Britain.”

….

‘“It was long afterwards,” he said, “after the Director had returned from the Third Heaven, that we were told a little more. This haunting turned out to be not only from the other side of the invisible wall. Ransom was summoned to the bedside of an old man then dying in Cumberland. His name would mean nothing to you if I told it. That man was the Pendragon, the successor of Arthur and Uther and Cassibelaun. Then we learned the truth. There has been a secret Logres in the very heart of Britain all these years: an unbroken succession of Pendragons. That old man was the seventy-eighth from Arthur: our Director received from him the office and the blessings; tomorrow we shall know, or tonight, who is to be the eightieth. Some of the Pendragons are well known to history, though not under that name. Others you have never heard of. But in every age they and the little Logres which gathered around them have been the fingers which gave the tiny shove or the almost imperceptible pull, to prod England out of the drunken sleep or to draw her back from the final outrage into which Britain tempted her.”

….

‘“So that, meanwhile, is England,” said Mother Dimble. “Just this swaying to and fro between Logres and Britain?”

‘“Yes,” said her husband. “Don’t you feel it? The very quality of England. If we’ve got an ass’s head, it is by walking in a fairy wood. We’ve heard something better than we can do, but can’t quite forget it … can’t you see it in everything English––a kind of awkward grace, a humble, humorous incompleteness? How right Sam Weller was when he called Mr. Pickwick an angel in gaiters! Everything here is either better or worse than––”

‘“Dimble!” said Ransom….

‘“You’re right, Sir,” he said with a smile. “I was forgetting what you have warned me always to remember. This haunting is no peculiarity of ours. Every people has its own haunter. There’s no special privilege for England––no nonsense about a chosen nation. We speak about Logres because it is our haunting, the one we know about.”

‘“Aye,” said MacPhee, “and it could be right good history without mentioning you and me or most of those present. I’d be greatly obliged if anyone would tell me what we have don––always apart from feeding pigs and raising some very decent vegetables.”

‘“You have done what is required of you,” said the Director. “You have obeyed and waited. It will often happen like that. As one of the modern authors has told us, the altar must often be built in one place in order that the fire from heaven may descend somewhere else. But don’t jump to conclusions. You may have plenty of work to do before a month is passed. Britain has lost the battle, but she will rise again.”’

Let us be Logres in the midst of Britain.

Sincerely yours,

David