This is part seven of a series on WHEAT—an acronym to describe the Beautiful Gospel in a way that parallels the TULIP of Calvinism, the DAISY of Arminianism, and the ROSES of Molinism. See the previous articles if you haven’t already.

Russian icon, Wikimedia Commons.

Calvinism’s TULIP teaches that God’s grace is irresistible. That is, those whom God has elected cannot resist his call to salvation. Molinism’s ROSES asserts an “overcoming grace,” which is a nuanced way to say essentially the same thing. However, Arminianism claims that while God has freed all humans to believe, we also remain free to reject God.

On this point, I have no major objections to the Arminian position, though I’d like to press into it a bit further. But first I want to respond to the position of Calvinism and Molinism.

It’s bad enough that these two systems have God consigning half of humanity to eternal damnation, but irresistible grace makes things equally problematic for the elect. To put it bluntly, if grace were irresistible, then it would be a form of assault. If a “no” is ultimately not possible, then a consenting “yes” is also not possible. And if there is no possibility for consent, then God’s relationship with his elect is just as troubling as his relationship with the damned.

Calvinism and Molinism would claim that in reality, God simply continues to pursue the elect until their wills align with his. But given the unilateral control of God that is presupposed by these systems, along with the inability for humans to resist his “grace,” what this really describes is a form of brainwashing. It cannot be true consenting allegiance if there is no possibility for the elect to say no.

God’s self-giving kenotic love

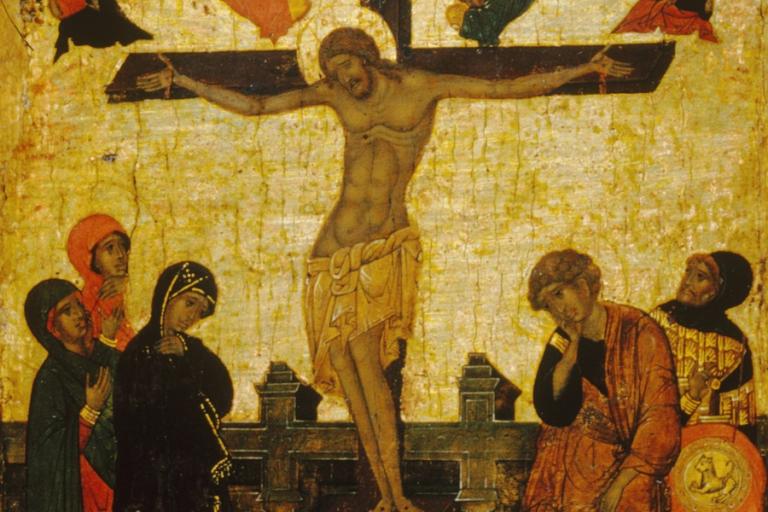

In contrast to the coercive God of Calvinism and Molinism, the God revealed in Jesus is one of kenosis—a Greek word meaning “emptying” or “self giving” that comes from Philippians 2:7:

Let the same mind be in you that was in Christ Jesus,

who, though he was in the form of God,

did not regard equality with God

as something to be exploited,

but emptied [ekenōsen] himself,

taking the form of a slave,

being born in human likeness.

And being found in human form,

he humbled himself

and became obedient to the point of death—

even death on a cross. (Philippians 2:5–8. NRSV)

No end of speculation surrounds this “emptying” of Jesus. What exactly did he empty himself of? Did it make Jesus less equal to God than he was before the Incarnation?

Any orthodox explanation of kenosis must say that no, Jesus did not become less equal to God. The Word who was in the beginning with God, and who was God, remains fully God when he becomes flesh and dwells among us (John 1:1–14). “For in him all the fullness of God was pleased to dwell” (Colossians 1:19, NRSV).

But the Beautiful Gospel, rooted in the belief that Jesus perfectly reveals God, gives us another way to look at kenosis. Rather than viewing kenosis as a one-time emptying that occurred at the Incarnation, we would say that Jesus’ Incarnation reveals God to be a God who is always engaged in kenosis. God is always giving of himself for the sake of his creation. God is kenotic love at his core.

Here’s how Brad Jersak describes it:

Far from giving up, hiding or hindering God’s nature, we shall see that Christ’s kenotic and cruciform life is the revelation par excellence of God’s glory. Kenosis is not a surrender of the divine attributes; kenosis defined as self-giving or self-donation is the premier expression of God’s nature—of God’s love and grace—seen most clearly on the Cross. (A More Christlike God, p. 99 )

So when I say kenosis, I am talking about love. Cruciform love, as revealed through Christ’s Passion, is none other than authentic, willing consent to ‘otherness.’ Love is, by nature, willing and consensual, self-giving and self-sacrificial. (A More Christlike God, p. 101)

Because God is such kenotic love in his very essence, he cannot violate consent or free will. To do so would be to violate his own nature.

Thus “irresistable” or “overcoming” grace is out of the question. But so is a grace that comes with conditions or an expiration date. God’s grace is absolute. God is constantly giving of himself to all of creation, with no limitations and no strings attached.

Here again is Brad Jersak, using the Bridegroom imagery of Christ to speak about these two pitfalls of a grace that is not based on kenotic love:

Without going into great detail here, might I suggest that because God, by nature, is the eternally consenting Bridegroom, there are two things he cannot and will not do:

- He will not ever make you marry his Son, because an irresistible grace would violate your consent. Your part will always and forever be by consent.

- His consent will never end, because a violent ultimatum would violate your consent. Divine love will always and forever be by consent. Emphasis on forever. “His mercy endures forever” (Psalm 136). “I have loved you with an everlasting love; I have drawn you with unfailing kindness” (Jer. 31:3).

I don’t believe the divine courtship involves wearing you down with his love until you give up. It’s simply that he’ll always love you, with a love that even outlasts and overcomes death (Song of Solomon 8). The Bible at least hints (Rev. 21-22) that the prodigal Father will wait for you, invite you and keep the doors open for you until you’re ready to come home. He’ll wait for you forever. (A More Christlike God, pp. 126–127)

In the previous post, we asked whether we could be certain that every individual would eventually accept God’s reconciliation.

Having now considered the necessity for consent, I would have to say no. We cannot be certain. But we can certainly hope! We can hope in the strongest sense of the word, having complete assurance that the God who is love will exhaust the full power of love to draw everyone to himself, yet without ever violating consent.

And what happens when we do submit to God’s love and accept his reconciliation? In other words, what does salvation look like? We’ll address this question in the final point of WHEAT—“transformative love.”

All posts in the Beautiful Gospel of WHEAT series: