This is part eight of a series on WHEAT—an acronym to describe the Beautiful Gospel in a way that parallels the TULIP of Calvinism, the DAISY of Arminianism, and the ROSES of Molinism. See the previous articles if you haven’t already.

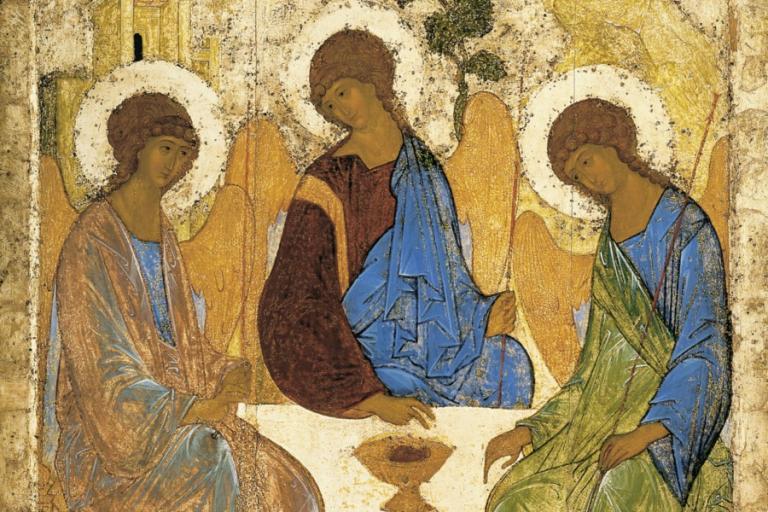

by Andrej Rublëv, Wikimedia Commons.

We’ve now made it to the final point from each of the theological systems we’re considering. This last point questions whether salvation can be lost. Calvinism’s TULIP teaches the perseverance of the saints, which means that God’s elect cannot lose their salvation. Molinism’s ROSES similarly teaches that believers are eternally secure in their salvation. Arminianism has no single official position on this. While the DAISY acronym would suggest that believers can lose their salvation, the FACTS acronym would suggest that that their salvation is secure. And you’ll find Arminians landing on both sides of this debate.

Regardless of which side of this debate any individual might take, all three systems are united by an understanding of salvation that is primarily focussed on our afterlife destination. In other words, when Calvinists, Molinists, or Arminians alike refer to salvation, they are usually talking about salvation from hell. Furthermore, this salvation is typically framed in terms of an event—one’s “salvation experience,” or the moment in time that someone said a prayer and “got saved.” It is really only within this framework that the question even makes sense to be asked, whether those who “are saved” could “lose their salvation.”

By contrast, the Beautiful Gospel, while not denying the reality of hell (at least when properly understood), would argue that hell is far from being the primary focus of salvation. And while we who hold to the Beautiful Gospel may reference a point in time when we committed to following Jesus, we would not tend to think of that as the moment of our salvation.

If we wanted to pinpoint a time of salvation, we might point to that moment when the eternal Word of God wrapped himself in human flesh and entered our world through the virgin’s womb. When Jesus’ divine nature merged with our human nature, so too did our human nature assume the divine, and our salvation was secured. Or we might point to Jesus’ life and ministry. As he taught by word and action what perfect love looks like, he showed us the way of his salvation. Or we might point to Jesus’ crucifixion and resurrection. By entering into death, he abolished death’s power once and for all.

But salvation is much more than any past-tense event. It is primarily a present-tense process. We are currently being saved every moment of every day. And it is also a future-tense state. The time is coming when our our salvation will be fully realized.

We have been saved. We are being saved. We will be saved. All three are true and necessary understandings of salvation.

Theosis—becoming God

In the previous points, we’ve already spent some time considering our past-tense and future-tense salvation. So I’d now like for us to examine the ongoing present-tense process of our salvation, known as theosis.

The concept of theosis is absolutely central to the Eastern Orthodox understanding of the gospel, but it is seldom if ever mentioned in most Protestant circles today. I think that’s a tragedy. Thankfully, this trend seems to be starting to change, as the Beautiful Gospel continues to spread.

Theosis is a Greek word, sometimes translated as “deification” or “divinization” (not to be confused with “divination”). As far as I’ve been able to tell, the term was first used in a Christian context by Gregory of Nazianzus in the fourth century. But the theological concept far predates the use of the term.

Athanasius famously (or perhaps shockingly, if you’re not familiar with it) summed up theosis this way:

He [the Word of God], indeed, assumed humanity that we might become God. (On the Incarnation, 54)

And of course Athanasius was just restating what others, like Irenaeus, had said before:

… the Word of God, our Lord Jesus Christ, who did, through His transcendent love, become what we are, that He might bring us to be even what He is Himself. (Against Heresies: Book V, “Preface”)

More recently, C.S. Lewis described the process of theosis like this:

The command Be ye perfect is not idealistic gas. Nor is it a command to do the impossible. He is going to make us into creatures that can obey that command. He said (in the Bible) that we were “gods” and He is going to make good His words. If we let Him—for we can prevent Him, if we choose—He will make the feeblest and filthiest of us into a god or goddess, dazzling, radiant, immortal creatures, pulsating all through with such energy and joy and wisdom and love as we cannot now imagine, a bright stainless mirror which reflects back to God perfectly (though, of course, on a smaller scale) His own boundless power and delight and goodness. The process will be long and in parts very painful; but that is what we are in for. Nothing less. He meant what he said. (Mere Christianity, “Counting the Cost”)

And Lewis too was restating what he learned from his “master,” George MacDonald, who wrote the following:

Paul’s idea is, that when we take into our understanding, our heart, our conscience, our being, the glory of God, namely Jesus Christ as he shows himself to our eyes, our hearts, our consciences, he works upon us, and will keep working, till we are changed to the very likeness we have thus mirrored in us; for with his likeness he comes himself, and dwells in us. He will work until the same likeness is wrought out and perfected in us, the image, namely, of the humanity of God, in which image we were made at first, but which could never be developed in us except by the indwelling of the perfect likeness. By the power of Christ thus received and at home in us, we are changed—the glory in him becoming glory in us, his glory changing us to glory. (Unspoken Sermons, “The Mirrors of the Lord”)

Nor is the concept of theosis without scriptural precedent. Lewis above references both Matthew 5:48 and John 10:34. And the quote from MacDonald was a comment on 2 Corinthians 3:18:

And all of us, with unveiled faces, seeing the glory of the Lord as though reflected in a mirror, are being transformed into the same image from one degree of glory to another; for this comes from the Lord, the Spirit. (2 Corinthians 3:18, NRSV)

Similarly, 2 Peter describes how we can actually “become participants of the divine nature” (2 Peter 1:4, NRSV). And Ephesians speaks of how we “may be filled with all the fullness of God” (Ephesians 3:19, NRSV), and also “attaining to the whole measure of the fullness of Christ” (Ephesians 4:13, NIV). That word fullness, by the way, comes from the Greek word pleroma, which is the same word used of Jesus to describe how “in him the whole fullness of deity dwells bodily, and you have come to fullness in him” (Colossians 2:9–10, NRSV).

So what does all this mean? Are we to actually become God? If you have in mind that we each individually become the eternal Creator of the universe, then no, that’s not theosis. To read the Church Fathers like that would be to over-literalize their language to the point of distortion. But at the same time, I fear that watering their language down to anything less than what they said would turn it into an understatement.

For myself, I’m trusting the wisdom of how they chose to phrase this concept of theosis. In a mystical sense (that ought not be literalized too far) we really do become God. We truly do share in the divine nature.

We will become just like Jesus. As for the specifics of what this looks like, 1 John teaches that “what we will be has not yet been revealed. What we do know is this: when he is revealed, we will be like him, for we will see him as he is” (1 John 3:2, NRSV).

This is theosis. This is salvation. This is the Beautiful Gospel.

Can we lose our salvation?

As I mentioned above, once we remove salvation from the context of a legal transaction to get us out of hell, it doesn’t really make sense to ask whether we can lose it. Salvation is not a contract that we can back out of.

Salvation—theosis—is the process of being transformed by God’s love into his image.

We can’t “lose” that salvation. But we can resist it. We have a choice. We can choose to cooperate with God and allow him to do his purifying work in us. Or we can choose to push back against his love and remain as we are.

For most of us, this process is a constant back and forth. We gladly work with God in some cases and certain areas, but we resist in others. We take some steps forward and some steps backward.

But the good news is that God doesn’t give up on us. Our resistance to his love could never dissuade him from seeking our good. Even for the most obstinate among us, God will continue to pour out his love for as long as any hope remains, in both this life and the next.

That’s it for the points of WHEAT. I hope you’ve enjoyed this series, and I hope that WHEAT will be helpful to you in explaining the Beautiful Gospel.

Since starting this series, I’ve already heard from a number of pastors and other church leaders who plan to teach from WHEAT. That’s really encouraging to me, and I’d love to hear from you if you plan to use WHEAT in your teaching. I’d also love to hear if you have any feedback on WHEAT in general.

Let me know in the comments below, or connect with me on Facebook. And be sure to subscribe to the blog!

All posts in the Beautiful Gospel of WHEAT series: