Like many upper middle class mainline Protestants, which is to say white Christians, I’ve long taken issue with the concept of divine wrath, believing it to conflict with the God whose most determinative attribute is Goodness itself. Whenever I’ve pondered the possibility of God’s anger I’ve invariably thought about it directed at me. I’m no saint, sure, but I’m no great sinner either. The notion that God’s wrath could be fixed upon me made God seem loathsome to me, a god not God.

I’ve changed my mind about God’s wrath.

Or, rather, my friend, Brian Stolarz has changed my mind.

When reflecting upon the category of divine wrath, thanks to Brian, I no longer think of myself. My mind goes instead to Alfred Dewayne Brown, Brian’s client.

Brian spent a decade working to free an innocent man, Alfred Dwayne Brown, from death row in Texas. Dewayne had been convicted of a cop-killing in Houston. Despite a lack of any forensic evidence, he was sentenced to be killed by the State on death row.

Brown’s IQ of 67, qualifying him as mentally handicapped, was ginned up to 70 by the state doctor in order to qualify him for execution. This wasn’t the only example of prosecutorial abuse in the case; in fact, the evidence which could’ve proved his alibi was hidden by prosecutors and only discovered fortuitously by Brian, years later. Dewayne was released by the state this summer. Brian has forthcoming book about the experience. You can find out more about the case here: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/inspired-life/wp/2016/01/21/making-friends-with-a-murderer-and-proving-hes-innocent/

Meanwhile, Dewayne has a civil rights case pending to seek restitution for the injustice done to him.

To seek rectification, biblically speaking.

I spent about a half hour alone with Dewayne this fall as we waited for his presentation, with Brian, to a group of law students. I’ve worked in a prison as a chaplain and interacted with prisoners in solitary and on death row. Like my friend, Brian, I have a good BS radar. Dewayne was unlike the prisoners I’ve met. My immediate reaction from spending time with him was how difficult it was for me to fathom any one fathoming him committing the crime of which he was accused. My second reaction was to feel overwhelmed by Dewayne’s expressions of forgiveness over the wrongs done to him by crooked cops and lawyers, a prejudiced system, and an indifferent society. ‘I’ve forgiven all that,’ Dewayne told me in the same sort of classroom where lawyers who had turned a blind eye to his innocence were once trained into a supposedly blind justice system.

Here’s the crux of the matter, and I use that word very literally:

Dewayne is allowed to express forgiveness about the crimes done to him.

But, as a Christian, I am not so permitted. Neither are you.

If we told Dewayne, for example, that he should forgive and forget, then he would be justified in kicking in our sanctimonious teeth.

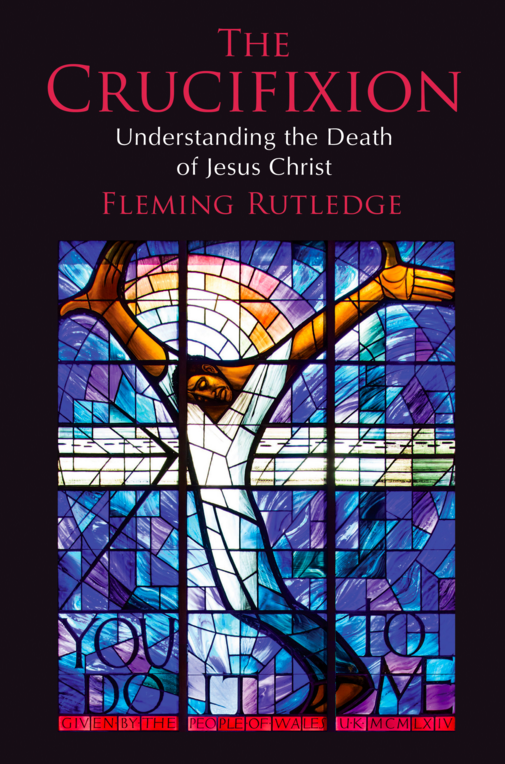

In The Crucifixion: Understanding the Death of Jesus Christ, Fleming Rutledge points out in her third chapter, The Question of Justice, we commonly suppose that Christianity is primarily about forgiveness. Jesus, after all, told his disciples they were to forgive upwards of 490 times. From the cross Jesus petitioned for the Father’s forgiveness towards us who knew exactly what we were doing. Forgiveness is cemented into the prayer Jesus taught his disciples.

Nonetheless, to reduce the message of Christianity to forgiveness is to ignore what scripture claims transpires upon the cross.

The cross is more properly about God working justice.

The most fulsome meaning of ‘righteousness,’ Rutledge reminds her readers, is ‘justice’ understood not only as a noun but as an active, reality-making verb. Though righteousness often sounds to us as a vague spiritual attribute, the original meaning couldn’t be more this-worldly. Justice, don’t forget, is the subject of Isaiah’s foreshadowings of the coming Messiah. Justice is the dominant theme in Mary’s magnificat and justice is the word Jesus chooses to preach for his first sermon in Nazareth.

To mute Christianity into a message about forgiveness is to sever Jesus’ cross from the Old Testament prophets who first anticipated and longed for an apocalyptic invasion from their God.

And it’s to suggest that on the cross Jesus works something other than how both his mother and he construed his purpose.

Rather than forgiveness, Rutledge asserts, we see on the cross God’s wrath poured out against Sin with a capital S and the upon the systems (Paul would say the Powers) created by Sin. On the correspondence between Sin as injustice and God’s wrath, Rutledge cites Isaiah’s initial chapter:

What to me is the multitude of your sacrifices?

says the Lord;

I have had enough of burnt-offerings…

bringing offerings is futile;

incense is an abomination to me.

I cannot endure solemn assemblies with iniquity.

Wash yourselves; make yourselves clean;

remove the evil of your doings

from before my eyes;

cease to do evil,

learn to do good;

seek justice,

rescue the oppressed,

defend the orphan,

plead for the widow…

Therefore says the Sovereign, the Lord of hosts, the Mighty One of Israel:

Ah, I will pour out my wrath on my enemies,

and avenge myself on my foes!

I will turn my hand against you…

Christianly speaking, forgiveness is a vapid, meaningless concept apart from justice. The cross is a sign that something in the world is terribly wrong and needs to be put right. The Sin-responsible injustice of the world requires rectification (Rutledge’s preferred translation for ‘righteousness’).

Only God can right what’s wrong, and the cross is how God chooses to do it. God pours out himself into Jesus and then, on the cross, God pours out his wrath against Jesus and, in doing so, upon the Sin that unjustly nailed him there.

Summarizing the prophets’ word of divine wrath in light of the cross, Rutledge writes:

‘Because justice is such a central part of God’s nature, he has declared enmity against every form of injustice. His wrath will come upon those who have exploited the poor and weak; he will not permit his purpose to be subverted.’

Despite the queasiness God’s wrath invokes among mainline and liberal Protestants, how could one think of Alfred Dewayne Brown and not hear the above lines as good news? The example of Dewayne Brown points out the problem with the popular disavowal of divine anger; namely, what we (in power) find repugnant has been a source of hope and empowerment to the oppressed peoples of the world.

The wrath of God is not an artifactual belief to be embarrassed over, it is the always timely good news that the outrage we feel over the world’s injustice is ‘first of all outrage in the heart of God,’ which means wrath is not a contradiction of God’s goodness but is the steadfast outworking of it.

The biblical picture of God’s anger, Rutledge shows, is different from the caricature of a petulant, arbitrary god so often conjured when divine wrath is considered in the abstract. ‘The wrath of God,’ she writes, ‘is not an emotion that flares up from time to time, as though God had temper tantrums; it is a way of describing his absolute enmity against all wrong and his coming to set matters right.’ Put so and understood rightly, it’s actually the non-angry god who appears morally distasteful, for ‘a non-indignant God would be an accomplice in injustice, deception, and violence.’

Maybe, I can’t help but wonder, we prefer that god, the one who is a passive accomplice to injustice, because, on some subconscious level, that is what we know ourselves to be.

Accomplices to injustice.

I did no direct wrong to Dewayne Brown, for example, but on most days I’m indifferent to others on death row like him. The inky facts of injustice are all over my newspaper but I don’t do anything about it. I try not to see color even as I neglect to see it through the prism of the cross.

I’m not an oppressor but I am most definitely an accomplice. Odds are, so are you.

Perhaps that is what is truly threatening to so many of us about a wrathful God; we know that the bible’s ire is fixed not so much on the hands-on oppressors as it is against the indifference of the masses.

As Rutledge points out:

’,,,in the bible, the idolatry and negligence of groups en masse receive most of the attention, from Amos’ withering depiction of rich suburban housewives (Amos 4.1) to Jesus’ lament over Jerusalem (Luke 13.34) to James’ rebuke of an insensitive local congregation (James 2.2-8).

As Brett Dennen puts it in his song, ‘Ain’t No Reason,’ slavery is stitched into every fiber of our clothes. We’re implicated in the world’s injustice even if we like to think ourselves not guilty of it. Rutledge believes this explains why so much of popular Christianity in America projects a distorted view of reality; by that, she means sentimental. Our escapist mentality protects us not just from the unendurable aspects of life in the world but also from the burden of any responsibility for them.

Such sentimentality, however popular and apparently harmless, has its victims. They have names like Alfred Dewayne Brown.

Having a friend like Brian and having met someone like Dewayne, I’m convinced we risk something precious when we jettison God’s wrath from our Christianity. We risk losing our own outrage.

Fleming Rutledge’s The Crucifixion might’ve convinced all on its own:

‘If, when we see an injustice, our blood does not boil at some point, we have not yet understood the depths of God. It depends on what outrages us. To be outraged on behalf of oneself or one’s own group alone is to be human, but it is not to participate in Christ.

To be outraged and to take action on behalf of the voiceless and oppressed, however, is to do the work of God.