I talk to the cabbies.

Where are you from?

They answer: Ethiopia, Sudan, Libya, Jamaica, Mississippi.

What brought you to DC?

A better life.

Then they tell me about the people they knew before they came to D.C.. The sisters, the cousins, the aunties, the brothers. They speak about how they miss their mamas and their daddies, some haven’t seen their parents in decades.

They ask me where I live.

Oregon, I reply.

What brings you here? they ask.

My father’s name is on the Wall.

He was killed in Vietnam? they ask.

Yes.

How old where you? That’s the most frequently asked question I get by anyone who learns of my father’s death: How old were you?

It was the question the Gold Star President asked me last night on the lawn in front of the Capitol. She, who had lost her beloved son to a roadside bomb.

I was fortunate, I replied. I was nine.

It is how I feel now, although, it was not how I felt for much of my growing up years.

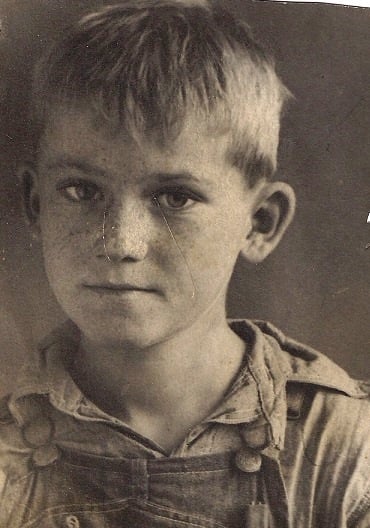

The little boy I met later, standing on the folding chair, was younger, six or seven. Her daddy died, too, his mama said.

When I was young like you, I said.

His eyes grew wider. He stared, looking for signs, I suppose, that I was a young girl, once.

His daddy died at war but not in the same way as mine. His daddy took his own life, unable to cope with the survivor’s guilt he felt over his own identical twin brother, who lost a leg to an IED.

As I watched the flags waving, I wondered, do the men and women who send others off to war — do they ever experience survivor’s guilt?

Twenty-two suicides by veterans every single day.

That’s the number now.

That’s a classroom full of kindergartens, all grown up.

The cabbies I talk to, a lot of them know war and its repercussions. Many of them fled their own homelands because of war and how it ravaged the country economically, spiritually, physically. They have sisters who’ve been raped, aunts who were mutilated, friends who were tortured, brothers who were killed.

They listen to talk radio, these cabbies, and they think a lot about the politics of this country, and the politics of the country they left behind.

Human nature isn’t much different, culture to culture.

Corrupt people in power can ruin it for all the rest of us.

The cabbies grow quiet when I tell them my father’s name is on the Wall.

They offer their condolences with heavy sighs and gracious words usually couched in some commentary about war and its ills, or politicians and their wrongheaded approach to foreign policy.

In our grief, we agree.

I feel a kinship with the cabbies who fled their war-torn countries. I don’t know the horrors they endured as children, as teenagers, or as young adults. But I know enough about war to imagine.

Part of any remembering is imagining.

When we lose our ability to imagine what life must be like for another, we lose an essential part of our humanity: empathy.

I saw it in that young boy’s eyes as he stood there on that folding chair searching my face for the young girl who like him was fatherless.

And I see in the dark eyes of the cabbies as they glance in their rear-view mirrors at me.

What is it you see in the rear-view mirror, looking back, imagining, remembering?