Many of you have been following Alecia Faith Pennington’s situation. You can read my other posts on her story here, but in sum, Alecia Faith released a youtube video explaining that she does not have a birth certificate and cannot prove her identity, and stating that her parents had refused to help her. Alecia Faith’s mother, Lisa Pennington, a popular homeschooling blogger and speaker, responded by claiming that she and her husband have offered to help Alecia Faith. However, a perusal of Lisa’s blog rather confirms Alecia Faith’s story byrevealing her to be a controlling mother who kept even her adult children on a tight leash.

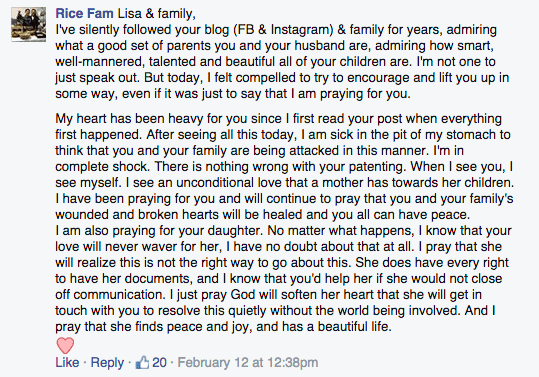

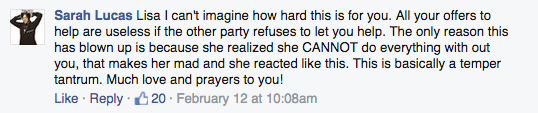

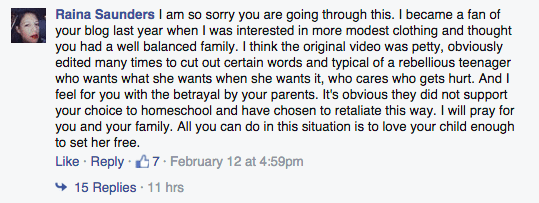

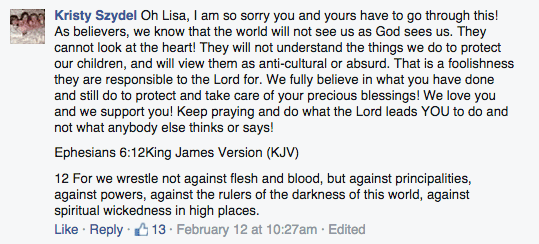

Today I want to talk about some comments on Lisa Pennington’s Facebook page, comments from homeschooling moms comforting Lisa in her “time of trouble” and praying that Alecia Faith’s heart will be “softened” and that she will turn to the embrace of her loving parents. I’ve seen this sort of thing before. Here’s a sampling:

How familiar this all feels.

The idea of the prodigal is a strong trope in evangelical and fundamentalist culture. The problem is, first of all, that that any child who steps out of line is by default portrayed as a prodigal. And second, the problem is that because the story of the prodigal son ends with the son coming home in rags and begging forgiveness, that is the expectation here as well—that our actions are temporary and that in the end we’ll come back all apologetic.

I totally get that young adults sometimes make unwise decisions, and that sometimes they even make extremely bad decisions, such as becoming involved with meth or cocaine or getting in trouble with the law. I get that, and I can only imagine how difficult it would be, as a parent, to see your child head in that direction. But that’s not what we’re talking about here.

In evangelical and fundamentalist culture, any child who does not tow the party line risks being labeled rebellious and, ultimately, becoming a prodigal. And I should note that their prodigal status is rarely self-inflicted. Rather, adult children who choose different beliefs or make different lifestyle choices are treated as outsiders—as rebellious children, even. Emotional manipulation is applied in an attempt to bring them back to the fold. Is it any wonder many of these young adults choose distance as a result, sometimes cutting off contact entirely? It’s incredibly uncomfortable to be treated as an outsider and a problem by your own family, to say the least.

Then the parents’ church community and friends inevitably rally around them, offering comfort and support and offering to pray for God to change the prodigal’s heart. The focus is on how hard this must be for the parents, and the prodigals themselves are rarely actually asked for their side of what happened. Everything becomes about the parents, and how horribly difficult this situation is for them. No one considers that this situation might be difficult for the prodigal.

I was that child—that prodigal. I am that child—that prodigal.

When I chose some beliefs of my own, apart from my parents, I shifted from golden daughter to problem child. When I rejected my parents’ authority over me by refusing to break up with my boyfriend, things got worse. Need I note that I was twenty years old at the time? And my boyfriend? Why did they want me to break up with him? Was he a criminal, or an addict, or abusive toward me? Nope. His crime was not sharing all of my parents’ religious beliefs. He is now my supportive husband and life partner, dedicated father of my two children and hardworking co-provider for our family. Thinking you have the right to decide who your adult child can or can’t date rarely ends well—for you, that is.

My parents almost boycotted my wedding. They came, in the end, and sat in the back. My younger siblings were not allowed to participate in the ceremony as I had hoped. That’s not surprising, perhaps, because at that time whether I would be allowed to visit home and see my siblings in question. After the ceremony, my mom told me she and my dad had decided Sean and I would be allowed to visit. She said it like she was making a concession.

Leaving hurt. It was the hardest thing I’ve ever done. I was forced to choose between my family and my freedom, and given that choice I chose to run. It hurt to know that my parents were talking to my friends’ parents about me, twisting what had happened beyond recognition and portraying me as rebellious and wayward. It hurt to have to leave my siblings, my friends, my church community, everything. It was hard—very hard—to be suddenly alone in arranging things like housing or employment, with no parents or mentors to go to for advice. But my pain was invisible, swallowed up in the pain of my parents.

My parents are the ones who set out with a very specific end goal in mind when approaching childrearing—i.e., that the children turn out to share their beliefs and lifestyle choices. I didn’t chose that. They did. But children are wild cards, and don’t always conform to parental expectations—especially when those expectations are rigid or constrictive. In communities like mine—and Alecia Faith’s—children who don’t conform are too often cast aside, and a prodigal is born.