By David Khalaf

My former therapist is dead.

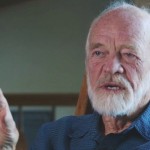

The news came out of Los Angeles this week that Joseph Nicolosi, one of ex-gay therapy’s greatest champions for decades, died of complications with the flu at age 70. Some members of the LGBTQ community may offer flippant reactions or begrudging respects. Those who struggled under the weight of his therapy may feel a quiet sense of relief. Me, I’m mostly sad.

I saw Nicolosi on and off for six years, from roughly 1997 to 2002. When I came out to my family at age 19, my parents offered no angry words or accusations of sin, only sadness and expressions of love. But being gay just didn’t seem like an option. It was shameful. I was shameful. So we agreed that I would try reparative therapy for a season. We didn’t know what else to do.

Nicolosi was the therapist to go to for same-sex attractions. It was like going to Stephen Hawking for advice on theoretical physics, or Richard Simmons for jazzercise classes. Nicolosi was one of the founders of NARTH, the National Association for Research & Therapy of Homosexuality, which was created in 1992 after the American Psychiatric Association had, according to NARTH, “totally stifled the scientific inquiry that would be necessary to stimulate a discussion about homosexuality.” He and his staff have treated thousands of clients over the years in what is the largest office dedicated to the issue of same-sex attractions. Even after Exodus International imploded in 2013, NARTH and Nicolosi lived on.

I was still a freshman in college when I started therapy. My time with Nicolosi was intricately tied to football games, final exams, and late nights working at the school newspaper. Therapy ran parallel to my collegiate life, a secret alternate reality to the persona of confident young adult I was trying so hard to create. I would disappear from campus for a few hours each week to make the drive from downtown Los Angeles up to Encino. Nicolosi’s dark, cozy office was located in a nondescript building a few blocks from the freeway. I went to therapy on my time, but on my parents’ dime (and at something like $120 a pop, I think I was getting the better end of the deal). My first time there I asked Nicolosi if he validated parking. “We validate feelings,” he said, “Not parking.” He didn’t lack humor.

The man was an enigma to me. He had built up walls so long and high it would make Donald Trump jealous. I think he needed to keep that professional distance, even more than a normal counselor. His clients were men sinking in the shame of their desires, aching for affirmation. Feeling broken, they longed for acceptance, but Nicolosi wasn’t the one to give it to them. I got the sense he didn’t want to get too close—that would be messy. So instead he engaged us with clinical interest, superficial banter, and occasional kind words.

Our sessions typically involved me talking, or sitting there trying to identify a feeling, while he quietly listened, scribbling inscrutable observations on his notepad with his blue pen. Half of my attention went into trying to interpret his chicken scratch so I could discover just how messed up I was. I think he wrote sloppily on purpose. He wore a uniform of his own design: baggy slacks with an ill-fitting dress shirt, and never a tie. He was in perpetual need of a haircut. When he spoke it was forceful and confident. I don’t remember him ever expressing doubt. Maybe that’s why I followed him for so long.

I don’t think Joe Nicolosi cared about me as a person. In fact, I doubt he would even remember me if he had seen me before his passing. He sometimes double-booked my appointments and seemed to forget my name unless my file was in his hand. I was already oversensitive at that point in my life, and it felt like being abandoned. But maybe I’m wrong. Perhaps these slights were a challenge for me to assert myself, as he often claimed gay men needed to do in order to reclaim their masculinity. Perhaps the boredom and indifference I sensed from him was merely his professional demeanor masking a deep concern for my wellbeing. I don’t think so.

And so we must ask ourselves: What good is a therapy that purports to save some lives if it takes others?

Whether or not Nicolosi cared about the individual people, I do believe he cared about the issue. Based on his theology and his beliefs about human sexuality, he had devised a psychological theory to explain homosexuality. He believed men and women experiencing same-sex attractions could change their orientation, and he genuinely wanted to see his theories realized in the lives of people who were desperate for change. I remember him telling me in my first meeting that if I didn’t want to change that I shouldn’t. His therapy was only for those who were dissatisfied with their sexual orientation. He was also straightforward in admitting that most of his clients experienced only degrees of change. I respected his honesty. And although people have wasted many years and many dollars caught up in the tangle of his therapy, it was, in my experience, never abusive or intentionally demeaning. Reparative therapy led me off course for many years, and it deepened my shame rather than alleviating it, but he was not intentionally cruel. I can blame Nicolosi for misdirecting people, but not for mistreating them.

His intention, however, does not excuse the damage reparative therapy has inflicted on so many LGBTQ people. Reparative and conversion therapies have caused gay people to feel fundamentally broken and irrecoverably sinful. This kind of therapy has shattered not only people’s self-worth but their spiritual connection to God. Those whose lost faith might call themselves lucky, for others lost even the will to live. These people took their own lives. And so we must ask ourselves: What good is a therapy that purports to save some lives if it takes others?

Nicolosi made a convincing case for the psychological underpinnings of homosexuality. It’s another reason I stayed with him for so long. I’ll even risk criticism by saying that some of his ideas around shame and attachment loss have merit. But what I witnessed over the years, both in myself and in the majority of men who went to him, was an utter lack of change. That, to me, was more compelling evidence than any theory he could ever offer. In the men’s groups I attended both through Nicolosi’s practice and later in life, the one thing I witnessed time and again was men trapped and defined by their struggle. There was no joy in their story; there was no fruit in their lives. Only after that epiphany did Spirit begin talking to me, leading me to a different truth about my sexuality.

I’ve had dreams about visiting Joe Nicolosi one day, asking him what he truly thought of me, and what all those chicken scratch notes really meant. Did he ever fear that his theories were a load of bullshit, and that he was leading people astray? Did he really believe in what he was pushing, or had he merely discovered a lucrative business model? Was he doing God’s work or his own? I’ll never know.

It feels like a part of my history has died with him. I grieve, if not Nicolosi directly, the formative season we shared together, when life was a tempest of pain and confusion, a back-and-forth tide of growth and regression. And I choose to remember the one time—when I was feeling particularly alone, during a season of life when I was numb with desolation—that the therapist who kept such strong professional boundaries, who didn’t seem to particularly care for me, stood up and offered me a hug. I will credit him that one act of kindness. And for that, at least, I will mourn him.

David Khalaf is a fiction writer living in Portland. He is now married to Constantino Khalaf and together they write the blog Modern Kinship.

Like our Facebook page and follow us on Twitter for more.

Image from josephnicolosi.com.