A pair of recent, thoughtful pieces from our friends at Religion News Service explore the church-based sanctuary movement through the lens of civil disobedience. First from RNS was Kimberly Winston’s look at how sanctuary churches may be at odds with American law under the Trump administration, “Sanctuary for the undocumented comes with legal consequences.” Then came Dave Gushee’s column, “An ethical analysis of the ‘New Sanctuary Movement.'”

Both of these examine the current movement with an eye toward the sanctuary movement of the Reagan years, when many liberal churches attempted to provide asylum to refugees fleeing the violence of American proxy wars in Central America. Gushee is upfront about viewing that as the historical precedent for current talk about sanctuary:

I encountered the first “Sanctuary Movement” in the 1980s, when some churches organized to shelter Salvadorans and Guatemalans who were at risk of being sent back to their violent and repressive homelands during the Reagan Administration. Since then the concept has never really gone away, and it is spiking today as the new Trump Administration has made clear its intent to heighten immigration-law enforcement.

The current wave of sanctuary talk borrows from that movement of 30 years ago in discussing sanctuary as a form of “civil disobedience.” I’m not sure that’s a helpful way to think about it. I’m not a lawyer or an ethicist or in any way an expert on this subject, but I don’t think the framework of civil disobedience is a good fit here.

Sanctuary is too old for that. This is a practice that goes back thousands of years in various forms, and one essential thing about all that long history is this: Sanctuary has always been completely legal.

So before turning to those RNS articles about the current moment in American life, let’s take a step back and review some of that very long history of sanctuary as a legitimate and legal practice — a tradition that was never outside of the law, but rather a part of the legal process. More than that, really, since sanctuary predates anything quite so formal as a “legal process.” In its earliest forms, it was actually something that enabled something like a legal process to be developed.

We can see this in the books of Moses, which outline the laws for sanctuary in “cities of refuge” within the land of Israel. Here’s Numbers 35:9-15:

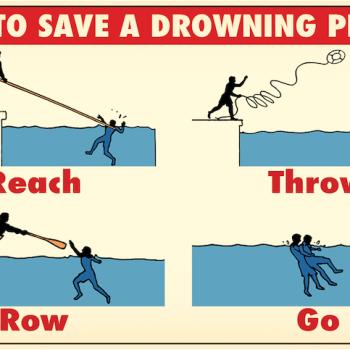

The Lord spoke to Moses, saying: Speak to the Israelites, and say to them: When you cross the Jordan into the land of Canaan, then you shall select cities to be cities of refuge for you, so that a slayer who kills a person without intent may flee there. The cities shall be for you a refuge from the avenger, so that the slayer may not die until there is a trial before the congregation.

The cities that you designate shall be six cities of refuge for you: you shall designate three cities beyond the Jordan, and three cities in the land of Canaan, to be cities of refuge. These six cities shall serve as refuge for the Israelites, for the resident or transient alien among them, so that anyone who kills a person without intent may flee there.

These cities of refuge were Levite cities — priestly cities of the priestly clan and priestly class. They were a kind of holy place for the Israelites. In other places and among other peoples at that time, the same kind of refuge was provided by their priestly classes in their holy places — at Greek temples and shrines and those of other ancient religions.

This is one of the ancient forms of sanctuary — the provision of temporary refuge for accused/presumed criminals “until there is a trial before the congregation.” Those provided refuge were criminals, but the sanctuary provided for them wasn’t a way of fleeing from the law, but rather of fleeing to the law. These places of refuge provided shelter from lawless vengeance and mob justice. This form of sanctuary was itself a lawful practice, and a necessary part of what enabled these societies to have lawful practices.

This same form of sanctuary endured for centuries in Britain, where it was offered not in Levite cities or pagan temples, but in Christian churches and cathedrals. In a fascinating recent episode of Helen Zaltzman’s Allusionist podcast, she discusses this history with John Jenkins of the University of York and with Rosalind Brown of Durham Cathedral:

HZ: Since the mid-16th century, the word ‘sanctuary’ has carried the more general sense of a place of refuge, not necessarily a religious one. But before then, the word had a meaning that is a pretty big contrast to the modern sanctuary movement: for at least a thousand years in England, until James I abolished it in 1623, sanctuary was not for people fleeing injustice, but for people fleeing justice.

JJ: If you’d committed a crime, if you could get yourself to a place of religious significance — a church, a cathedral, even things like a monastery or an abbot’s house or even just land that belonged to the church or was near to it — then you were able to effectively evade justice for a period of time. … And after that period of time was up you might be asked to — you might be forced to — leave the country, or you could go to trial. So the idea is, it’s a sort of extrajudicial way of apparently evading punishment, at least for a short period of time.

HZ: In England, that period of time was usually 37 or 40 days, depending on where you sought the sanctuary.

JJ: The sanctuary rights in England are very different to those on the continent. In general the idea of being able to seek sanctuary having committed a crime is almost universal in Christendom and is reflected in many ways to the world in all sorts of different systems.

HZ: In ancient Greece there were sanctuary temples, as well as statues that served a similar purpose. And the Torah mentions six cities in Judea that had been designated as sanctuaries for people who unintentionally caused the death of another, so they might be spared from revenge killings. So the sanctuary concept was not new when it came into law here in England in the fifth or sixth century.

You should listen to that whole episode (or read the whole transcript) for much more on the strange details, rules and traditions governing the way sanctuary was practiced in Durham. If you like weird history, you’ll like this. (And if you don’t like weird history, well, you should.)

I don’t think it’s quite right to say, as Zaltzman does, that this form of sanctuary was “for people fleeing justice.” They were fleeing from the informal “justice” of vengeance, but they were also fleeing toward formal justice in the form of either a trial or of exile. This form of sanctuary always existed within the law.

All the way back, of course, this form of the ancient tradition of sanctuary existed alongside the more familiar idea of the sort being revived and practiced by those American churches in those RNS articles. This more familiar form of sanctuary doesn’t involve temporary refuge for those presumed to be guilty, but indefinite refuge for those presumed to be innocent.

That other form of “sanctuary” practiced by Levite cities of refuge and by the cathedrals of medieval England gradually faded as more formal legal systems developed. Formal courts of law removed much of the need for that practice, taking on the guarantee of safety before trial that it had previously provided. But the parallel form of sanctuary — indefinite refuge for the innocent fleeing injustice — has remained necessary, and it endures.

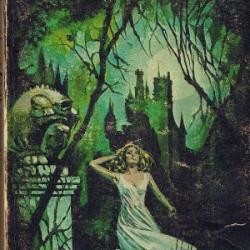

This enduring idea of sanctuary is best illustrated, I think, in a famous scene from Victor Hugo’s The Hunchback of Notre Dame. Here is that scene in the Charles Laughton and Disney adaptations. First, from the 1939 classic film:

And the same scene, Disneyfied, in the 1996 animated film:

This is mainly the sort of thing we have in mind when we speak of “sanctuary” — Quasimodo swooping in to rescue Esmeralda from execution, whisking her back inside the walls of Notre Dame Cathedral where she is safely out of the reach of her would-be executioners. In this idea of sanctuary, the cathedral serves like “base” in a game of tag — an inviolate refuge outside of the usual legal jurisdiction (no “apple trees”). And, just like in that children’s game, being safe on base is part of the rules.

To illustrate how enduring this ancient idea still is, just look at another common way we use the word “sanctuary” today, as a designation for nature preserves — for “wildlife sanctuaries” and “bird sanctuaries.” These are special places set apart — sanctified — as refuges for the preservation of endangered life. They are not outside the law, but they are governed by a different set of laws, and the usual laws may not apply there.

That’s the same general idea as the “Sanctuary! Sanctuary!” Quasimodo proclaims in the scenes above. And the same general idea advocated by sanctuary churches.

And again, this form of sanctuary is sanctioned. It doesn’t involve disobedience or law-breaking. In Hunchback, Notre Dame’s prerogative of extending sanctuary is its legal right. Esmeralda is safe there not because of the strength of the cathedral’s walls, but because the same law that sought to execute her also makes it illegal to violate the sanctity of that sanctuary. If you read Hugo’s novel or watch that full clip from the Laughton movie, you’ll see how this idea of sanctuary always involved a negotiation between competing jurisdictions — both of which were legitimate and legal.

That’s still true today, as we can see from what is probably the most famous current example of a person finding refuge in this form of sanctuary. I’m referring to Wikileaks founder Julian Assange, who has been living in the Ecuadoran Embassy in London since 2012. Assange, who is Australian, was arrested in the UK, from which he was to be extradited to Sweden to face trial on allegations of sexual assault and rape. (Assange denies those charges and insists that his asylum in the embassy isn’t due to those actual criminal charges but rather to his fear of being extradited to America to face as-yet-unspecified charges for his role in leaking classified information from the U.S. government.) By staying within the embassy, Assange puts himself on the sovereign soil of Ecuador, and that is what protects him from arrest and trial by British or Swedish authorities.

This is the same mechanism that protected Esmeralda once Quasimodo secured her within the walls of the cathedral. In that time, in Paris, that cathedral was its own sovereign territory, and its sovereignty was respected by the King of France as a matter of French law. Alas for Esmeralda, the balance of power between the competing sovereignties of pope and king, church and state, was not as firmly inflexible as the contemporary balance of power that recognizes the national sovereignty of embassies, thereby ensuring Assange’s refuge in a building that is in London yet also not part of London.

My point here is that those receiving the protection of sanctuary are not thereby breaking the law. They have physically relocated from one jurisdiction to another, placing themselves within a different legal framework, but not outside the law. Sanctuary isn’t mainly about physical protection, but about legal legitimacy. The corrupt Parisian officials seeking the death of Esmeralda might have been physically capable of storming the cathedral to recapture her. They weren’t prevented from doing so by the strength of the cathedral’s guards, but by their own law which also, in part, conceded the legal legitimacy of the cathedral’s jurisdiction. So too it isn’t Ecuador’s military might that prevents Scotland Yard from kicking in the doors of their embassy to re-arrest Assange. The British police refrain from doing so because their own law recognizes the legitimacy of Ecuador’s sovereign prerogative to grant such asylum. Sanctuary is legal.

There’s a big difference, though, between Esmeralda and Assange. I don’t just mean that Esmeralda was fictional, or that she was not a creepy sexual predator (allegedly), or even that her legal innocence was firmly established. Assange has been granted sanctuary by Ecuador, a modern, secular nation. Esmeralda’s sanctuary was provided, instead, by ecclesiastical authority dependent, in part, on some notion of a kind of spiritual jurisdiction.

This leads us to a much trickier, harder-to-articulate aspect of this idea of sanctuary, so let’s leave off here and come back to that in a bit.

For now I just want to stress this first main point: Sanctuary has never been an outlaw practice or a form of disobedience — “civil” or otherwise. It has always been, instead, an assertion of jurisdiction recognized as legal. I think that’s still true today.