The Republican Party has an evangelical problem.

My very simplistic theory of American presidential politics over the past half-century is that when Republican nominees have the overwhelming support of evangelical Christians, they win. See Richard Nixon, 1968 and 1972; Ronald Reagan, 1980 and 1984; and George W. Bush, 2000 and 2004. Particularly in the 1980, 2000, and 2004 elections, evangelical backing was

crucial, if not decisive.

One could probably include George H. W. Bush’s 1988 victory on this list. Despite the primary challenge from Pat Robertson, Bush courted evangelicals quite effectively in advance of general election before alienating them to a large extent over the course of his presidency.

Conversely, when Republican candidates lose when they don’t connect with evangelical voters and lack close relationships with evangelical leaders. See Bush, 1992; Bob Dole, 1996; John McCain, 2008.

Many pundits see the Religious Right as an albatross dragging the Republican Party to ever-more-certain defeats in a secularizing America. There is some truth to that argument. When Republican candidates become too closely associated with the Christian Right, they alienate other voters. Ironically, Bush’s desperate attempt to mend fences with the Religious Right during the 1992 campaign may have turned off voters uninterested in a culture war in the midst of an economic downturn. The Religious Right can be toxic to a candidate’s attempt to win the middle.

Moreover, one would presume that Republicans could take the votes of white evangelicals for granted. “Evangelicals voted Republican in 2008 because they had nowhere else to go,” writes Dan Williams in God’s Own Party, a detailed history of the Christian Right in America. [Even if you are already familiar with Dan’s book, see this recent discussion of his book.] Unless Tim Tebow runs for president as a Democrat (about as likely as Tebow throwing the football like Tom Brady, and he’ll have to wait until 2024 anyway), Republican presidential nominees are going to win large majorities of evangelical voters for the foreseeable future.

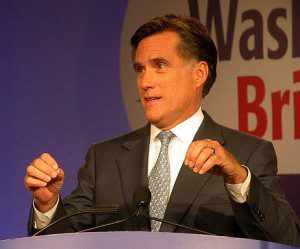

Still, I would argue that the level of evangelical support has been a critical factor in electoral outcomes over the past fifty years. And that bodes very poorly for Mitt Romney.

This is not primarily because of virulent evangelical anti-Mormonism. Last fall, Robert Jeffress gained attention for terming Mormonism a “cult” and Romney “not a Christian.” The media loves to run stories about evangelical ministers who say negative things about Mormonism. It makes for easy reporting.

Compare, though, anti-Mormonism in 2012 to anti-Catholicism in 1960. It’s pretty tepid stuff. Billy Graham probably wouldn’t have warmly spoken of Roman Catholics as “brothers in Christ” in 1960, as Joel Osteen recently did of Mormons. Rick

Warren questions Mormonism for its departure from trinitarian Christianity, but he hardly makes it sound sinister. Jeffress, moreover, has now decided he’d rather have a cultist than Barack Obama in the White House. [See, amid a hilarious discussion of political anti-Mormonism, Jon Stewart’s analysis of Jeffress’s change of heart]. Many evangelical leaders, as well as Christian Right organizations, have already lined up behind the presumptive Republican nominee. A large majority of evangelical voters will back Romney in the fall.

The problem isn’t whether most white evangelicals will support Romney. It’s the lack of evangelical enthusiasm. In what most commentators expect to be a close election, if evangelicals do not turn out in droves for Romney, encourage their neighbors to vote for Mitt, and become the heart of his grassroots operation, Romney has a much-diminished chance of winning. Romney is acceptable to most evangelicals, but simply far from ideal.

The problem includes but extends far beyond Romney’s faith. Evangelicals have gotten used to voting for one of their own, and Mitt isn’t. Moreover, conservative evangelicals would be skeptical of anyone who at least at one time positioned himself as a moderate in Massachusetts. Perhaps the only way that Romney might overcome the enthusiasm gap among evangelicals would be to select a bona fide evangelical Christian as his running mate. McCain probably helped himself with this approach in 2008, but let’s just say that his election also had drawbacks.

The conventional (and correct, in my view) wisdom is that evangelical Christian leaders have been far too beholden to the Republican Party for the past several decades. Evangelical voters, however, make up such a large portion of the Republican coalition that the party is also beholden to them, a reality that Republican politicians often forget until it is too late.

UPDATE: Note this analysis in the May 3rd issue of the Economist, within an article attempting to argue that young evangelicals are deserting the GOP:

“The prominence of evangelicals within the Republican Party is increasing: they made up more than half of all Republican voters in the first 16 primaries and caucuses where entry and exit polls were taken, up from 44% in 2008. And fully 70% of white evangelicals consider themselves Republican these days, up from 65% in 2008.”