In a recent New York Times column titled “Divided by God,” and more generally in his book Bad Religion, Ross Douthat laments the disappearance of the 1950s-era mainline Protestant/Roman Catholic establishment, a Christian center that once “helped bind a vast and teeming nation together.” Now, according to Douthat, we have become a “nation of heretics…in which most people still associate themselves with Christianity but revise its doctrines as they see fit, and nobody can agree on even the most basic definitions of what Christian faith should mean.”

This religious polarization, according to Douthat, is best illustrated by the 2012 presidential race, matching Barack Obama, an adult convert into the United Church of Christ, and Mitt Romney, a lifelong devout Mormon. (Until he dropped out of the race, Rick Santorum supplied another religious dynamic to the race: traditional Catholicism. As Douthat notes, an orthodox Christian may seem like the “weirdest heresy of all” in today’s spiritual milieu.)

Douthat is one of best conservative writers in America. In a brilliant 2009 move, the Times made him their youngest op-ed columnist in history, before Douthat turned thirty. He is a real cultural conservative, without the moderate, establishmentarian inclinations of the Times’ other conservative, David Brooks. However, I don’t think Douthat gets it quite right on this topic, because I think he underestimates how fractious the combination of religion and politics has always been in America.

Yes, religion feeds today’s dismaying polarization of American politics. Bemoaning our fractured political culture, our lack of “civility,” and our cheapened partisan uses of religion has become a favorite pastime of many pundits. But the polarization we are witnessing today is about par for the course in our nation’s history.

What if you go back to the nation’s founding? Surely back then we were more religiously unified? Well, yes and no. A very high percentage of Americans in 1776 were at least nominally Christian, and almost all of those were Protestants—about the only other religious groups were small numbers of Catholics and Jews. But many colonists had come as religious dissenters—Puritans, Quakers, and others—who were accustomed to furious fights over religion, dating back to the wars of the Reformation. The Great Awakening of the mid-eighteenth century had both re-energized and re-fractured the American religious scene, with many established Congregationalist and Anglican pastors facing charges that they did not preach the true gospel, and might not even be born again.

The great British orator Edmund Burke actually attributed Americans’ political fractiousness to their dissenting Protestantism: their religion, he wrote, was “a refinement on the principle of resistance.” Their faith was “the Protestantism of the Protestant religion.” The British better not trifle with these spiritual brawlers, he warned.

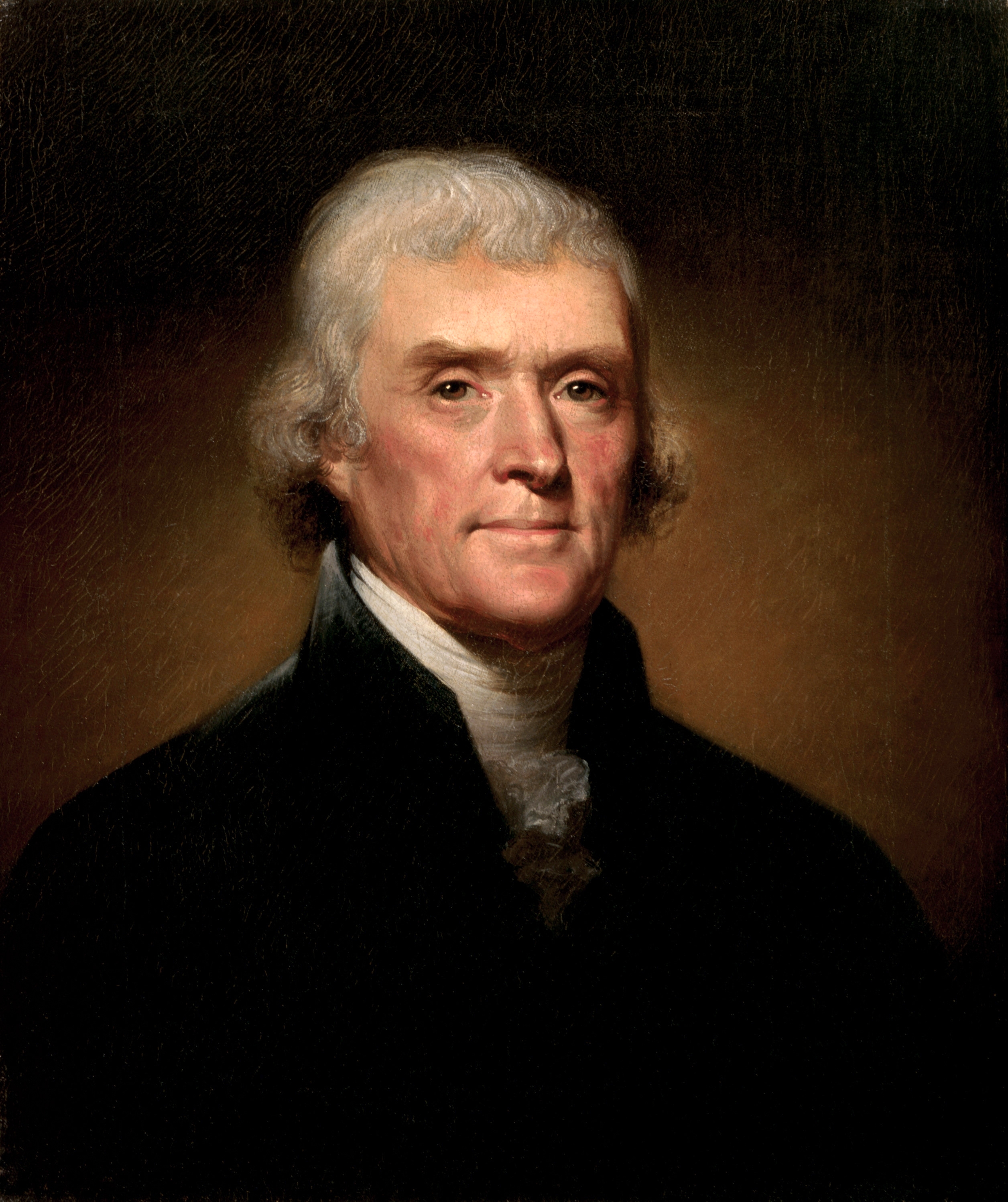

As I argued in my book God of Liberty: A Religious History of the American Revolution, Americans of the founding era did share religiously-grounded beliefs, such as the equality of all people before God, and the role of God’s Providence in human affairs. Those commonly-held ideas helped to unify the Revolutionary movement, and brought together Americans of vastly different personal beliefs, from evangelical Baptists to Deists such as Thomas Jefferson. But once the Revolution was over, Americans showed that they also remained prone to vicious religious feuds.

Nowhere was that fractious tendency better displayed than in the presidential election of 1800, in which Jefferson faced the incumbent John Adams. Although Adams was growing less orthodox in his beliefs, too, he was very comfortable with employing religious rhetoric as president. His supporters launched attacks on Jefferson’s faith that make today’s incivility pale in comparison. One writer called Jefferson a “howling atheist” (which he was not), and Adams’ Federalist party repeatedly and unapologetically ran an ad in the fall of 1800 telling Americans to ask themselves, “Shall I continue in allegiance to GOD—AND A RELIGIOUS PRESIDENT; or impiously declare for JEFFERSON—AND NO GOD!”

Perhaps Douthat is right, though, when he argues that Americans have lost a former semblance of orthodoxy. Prior to the 1960s, skeptics and “heretics” could certainly count on more universal condemnation when they publicly aired their views. Today’s mainline denominational hierarchies have given up almost any pretense to official orthodoxy or traditional moral norms. But this is an old story, too. Even by the early twentieth century, the “fundamentalist” movement was born as a reaction to theological slippage in the mainline denominations. Reformed theologian J. Gresham Machen concluded in 1923 that Protestant liberalism, with its emphasis on the “social gospel” and its doubts about biblical authority, had simply ceased to be Christian.

So yes, religion in contemporary America has no defined center, but I am not sure it ever had much of one to start with.