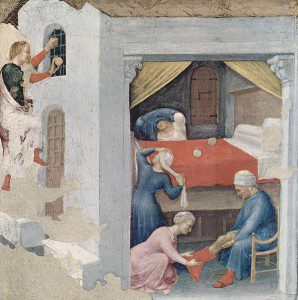

It’s a striking image: a man climbing up the side of a house and tossing three gold coins into the room of three poor young women. The funny thing about it is that the gift giver is missing his customary bright red suit and hat, white beard, and accompanying reindeer.St. Nicholas of Myra comes to life — as far as a reconstruction of his life out of much later sources permits — in Adam English’s The Saint Who Would Be Santa Claus.

I have to admit that I was skeptical about The Saint Who Would Be Santa Claus when I picked it up. Part of me likes the story of saints: exemplary lives, mortal and postmortal miracles, and — usually my favorite part of the story — the translation / robbery of relics. At the same time, for historians, saints are pretty inaccessible. No contemporaneous sources and the impossible task of separating hagiography from reality.

I set such concerns aside when I plunged into Adam English’s book. First, the robbery of the relics did not disappoint. As of 1087, it was a matter of time before Seljuk invaders moved into Myra and desecrated the grave where Nicholas had rested for six centuries. Thus, Italian raiders prepared to swoop in and carry off the bones (raiders from Baria made the move when hearing that the Venetians were preparing to do so). When the Barians went to the church of St. Nicholas, the monks were immediately suspicious. They knew what was coming. The standoff was tense.

Nicholas was a “myroblyte” (new term for me), “one whose relics secreted liquid,” in this case myrrh. In short, his bones oozed, the stuff dripped out of his tomb, and devotees swallowed it, rubbed it on their injuries, and treasured it as a relic. After the sailors overpowered the monks, a vial of Nicholas’s holy myrrh crashed onto the floor. It did not break. The monks took this as a sign that God wanted Nicholas removed.

One young Barian picked up an iron mallet and smashed away the pavement shrouding his tomb. When he opened the tomb, he found it “saturated in holy liquid,” giving off a paradisiacal fragrance. The same youth stepped into the holy myrrh. According to Nicephorus’s account of Nicholas, the young man “found the holy relics floating, and the sweetness of the scent filled the vicinity like an insatiable kiss reaching out to the venerable priests.” The translation of saints always makes for a great if unusual adventure story.

Out went the bones, taken to Bari, Italy, which still celebrates Nicholas’s arrival every May 9. Nothing like sanctifying a successful grave robbery.

My favorite section of the book, however, is English’s chronicle of Nicholas’s famous act of generosity, pictured above. At the age of eighteen, Nicholas (who lived on the southern coast of Turkey) lost his parents but gained their fortune. He soon heard of a man who because of a fall into destitution had resolved to prostitute his daughters. He had, after all, no money for wedding dowries, and his plans were lamentably common in the late-fourth century.

Learning of the father’s plight, Nicholas put some gold coins in a money pouch and anonymously tossed it into his home at night. When found the next morning, the father immediately made plans. “Without delay,” recounts one of the early chroniclers of Nicholas’s life, “he adorned the bridal chamber of his eldest daughter.” Pleased with the results of his almsgiving, Nicholas repeated his gift, paving the way for the second daughter to escape prostitution for matrimony. The father finally discovered Nicholas’s identity with his third gift.

English draws some useful ethical lessons from Nicholas’s actions. First of all, he compares Nicholas to Antony, who famously gave away everything in order to live as a monk in the Egyptian desert. (One of the book’s great virtues is the fact that Nicholas lived in such a tumultuous time in the history of Christianity and had so many fascinating contemporaries, such as Athanasius, Arius, and Constantine). Nicholas didn’t give away everything he had, and he didn’t become an ascetic. Instead, he made a meaningful and substantial gift to meet very immediate and specific needs. As English points out, a saintly action “need not be miraculous, angelic, or incredible.” Nicholas is a saint we can all successfully emulate. Finally, he not only saved a family from sin and poverty but affirmed the value of marriage.

Whether or not Nicholas the “microblyte” really filled his tomb with holy myrrh, English has given us a St. Nicholas all Christians can admire. One of the recurring themes in The Saint Who Would Be Santa Claus is redemption: from the redemption of a family from poverty and prostitution to the redemption of “pagan” holidays by suffusing dates such as December 25 with Christian meaning.

Christians can sometimes be rather cantankerous during advent. We complain about commercialism, the fact that some stores prefer “Happy Holidays” to “Merry Christmas,” and that there is simply too much to do in the span of several weeks. Our best recourse is to stop complaining and start imitating the man who became Santa Claus.

This post is part of the Patheos Book Club conversation about Adam English’s The Saint Who Would Be Santa Claus.