Although one could find fuller treatments of the subject elsewhere, I was very intrigued by Anne Applebaum’s thoughtful treatment of religion in Eastern Europe in the first decade after the end of WWII. [See the first part of this review of Applebaum’s The Iron Curtain here].

First of all, Applebaum allows for a healthy measure of gray instead of merely creating religious villains (collaborators / compromisers) and heroes (those who defied the Stalinist regimes).

Naturally, totalitarian regimes cannot tolerate the free expression of religion (in churches or outside their walls). “The nascent totalitarian states,” she writes, “could not tolerate any competition whatsoever for their citizens’ passions, talents, and free time.” Communist regimes even banned chess clubs. Thus, in 1946, East German communists in Saxony sounded the alarm because churches had organized their own “youth retreats and summer camps.” Soviet soldiers “marched into the forest and … ‘brought the children home.'” Despite that example, communist leaders handled churches with a relatively gentle glove. They appropriated large amounts of land from ecclesiastical control, but they arrested relatively few religious leaders and only gradually repressed church schools and other institutions. By the late-1940s, however, the grip tightened, as regimes shut down Christian charities and schools and arrested large numbers of priests.

Applebaum juxtaposes the response of two Catholic cardinals, Hungary’s József Mindszenty and Poland’s Stefan Wyszyński. “Both…,” Applebaum notes, “acted in good faith, according to what they thought best for religious institutions and for believers.” Mindszenty openly opposed Hungary’s communist government, seeking connections with American Catholics and denouncing the emerging dictatorship. He refused to sign an agreement with the regime without a return of the church’s confiscated property and a host of other provisions. For this, Mindszenty suffered arrest, torture, a show trial, and eight years in prison.

Wyszyński was far more circumspect and cautious. He sought to find points of agreement between Catholicism and communism, and he negotiated an “agreement of mutual understanding” with Poland’s communist government (signed in 1950). He promised not to support any anticommunist resistance, and he encouraged Catholic priests to “foster respect for the laws and prerogatives of the state among the faithful.” Many priests regarded it was “profoundly collaborationist.” For his cooperation, Wyszyński was awarded with his own arrest in 1953.

Applebaum notes that Mindszenty’s “open confrontation had the merit of clarity,” but it led to severe repression of the Hungarian church (following which, Hungary’s bishops signed an agreement with the regime “under far worse terms” than Wyszyński had signed in Poland). Wyszyński’s “more pliable tactics,” she notes by contrast, “had the merit of flexibility.” It enabled the Polish church to emerge from the Stalinist period (which ended with Stalin’s death in 1953) more intact. Taking a long view, Applebaum observes that unlike “the Catholic Church in Poland and the Protestant churches in Germany, the Hungarian churches did not play a large institutional role in the political opposition to communism that developed in the 1980s.” Applebaum is not praising collaboration over resistance, simply noting the crucial role of civil society in enabling resistance to totalitarianism.

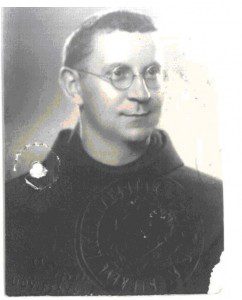

There are several other sections in The Iron Curtain in which Applebaum discusses Eastern European Christianity at length. She chronicles the Hungarian regime’s brutal treatment of Kedim, a Christian youth group organized by a Franciscan monk named Szaléz Kiss. [The government deemed Kedim “a fascist terrorist conspiracy group.”] Father Kiss was executed in 1948. Few American readers will have heard of Father Kiss — there are a number of such martyrs in The Iron Curtain.

I was also struck by the fact that religion not infrequently served as an entirely spontaneous source of resistance. In 1949, in Lublin (Poland), a local nun noted a change in the appearance of a Black Madonna of Częstochowa icon. Mary appeared to be weeping. “By evening,” Applebaum writes, “the doors of the cathedral could not be closed because of the size of the crowds.” At first, the regime ignored the flood of interest in the reported miracle. Then, even when the authorities curtailed train service and blockaded the roads into Lublin, thousands of people came, on foot in necessary. Soon, communist officials organized a demonstration in which they denounced “reactionary clerics.” Inside the Church of the Capuchins, the congregants sang, “We Want God!”, and when they emerged from that and other churches, the police arrested them. Soon, the bureaucrats blamed the whole affair on Voice of America. On a smaller scale, such miracles occurred across Eastern Europe.

Religion hardly dominates Applebaum’s book. She is primarily interested in the churches of Poland, East Germany, and Hungary because they represented an important part of civil society in those nations and continued to operate as institutions not entirely controlled by the state. Still, I appreciated Applebaum’s persistent and wide-ranging interest in the experience of Eastern European Christians during a perilous decade.